You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

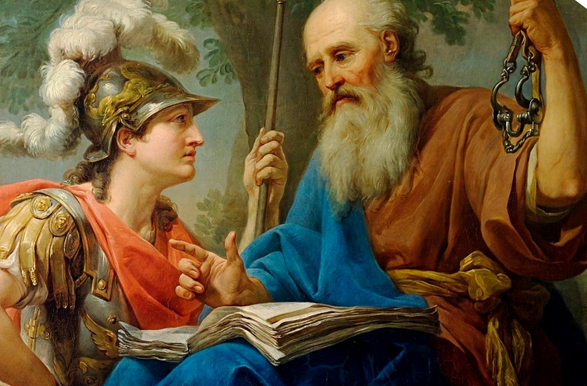

Marcello Bacciarelli, "Alcibiades Being Taught by Socrates"

Wikimedia Commons

From Socrates and Alcibiades to Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, history is full of mentor-mentee relationships that were not only intellectual, but also erotic, romantic or physical -- or all of the above.

The current moment is also rife with examples of mentor-mentee relationships that crossed the line into sexual harassment or assault, with devastating consequences for the mentee. Some of the transgressions are obvious and some are subtle, the latter kind often illustrating how fraught the idea of consent can be within academic power structures.

A new, already widely read essay in the Boston Review seeks to acknowledge the historical record -- and the fact that both teachers and students are human beings, with desires -- without condoning misconduct. It’s a hard line to walk, and reactions to “The Erotics of Mentorship,” by Marta Figlerowicz and Ayesha Ramachandran, both assistant professors of comparative literature at Yale University, have been mixed.

“Acknowledging the erotic force of pedagogical situations remains difficult, perhaps never more so than in the present-day U.S. university, whose governance is shaped by corporatized risk management and simplistic codes of conduct,” reads the essay, following a lengthy review of erotic mentorship over the millennia. “This is only made more complicated by the infusion of the very serious concerns raised by #MeToo.”

And yet, Figlerowicz and Ramachandran say, “intellectual magnetism, a notoriously protean force, often shades into erotic attraction.”

Such attachments are not the same as but are “compatible with” predatory sexual behavior, they wrote. But at “their best and most benign, they bring out our best selves -- the potentially heroic dimension of Eros chronicled by Plato -- driving us to develop nascent potentials into noteworthy accomplishments. That is what Alcibiades claims Socrates helps him achieve; and it is how Abelard and Heloise, and then Rousseau’s Julie and Saint-Preux, justify their ongoing correspondence.”

If Figlerowicz and Ramachandran were building a case for the normalization of eroticism in the classroom, they’d have stumbled a bit. They compare erotic mentor-mentee relationships to a “hall of mirrors” in which it’s unclear whether one wants to be -- or be with -- the other, for example, suggesting that consent might be impossible to give. Somewhat troublingly, they also recall their own experiences as students, saying, “We remain uncomfortably aware of having sought out meetings in hallways and over drinks after inspiring lectures in which the excitement of the conversation was clearly tinged with something more -- a shiver of heightened awareness, intensity, and passion that was both intellectual and sexual, perhaps sexual because intellectual. We did not necessarily want the former, but we were also unwilling to lose the latter” (emphasis Inside Higher Ed’s).

But the authors aren’t trying to promote erotic mentorship, per se: their essay deals in the what, not so much the why or how. (Figlerowicz and Ramachandran have written elsewhere about their current effort at Yale to "create an informal pedagogy of 'climate change' through a series of conversations, panels and informal lunches.")

In a joint email, Figlerowicz and Ramachandran said they indeed sought to describe a phenomenon, not prescribe a course of action.

“We are highlighting the importance of strong mentor-mentee relationships, when desired by both parties, while also recognizing that boundaries must be respected,” they wrote. “We are not advocating that people put up with any discomfort caused by the blurring of boundaries or the exploitation of power differentials (and obviously we don’t condone assault, etc.). But it does need to be acknowledged that some (many?) people also experience mentoring relationships as powerfully transformative and enabling, and that we should leave room for them too.”

As for their reference to not necessarily wanting to engage in anything beyond the intellectual with mentors or those academics they otherwise admired, but not wanting to risk losing out, Figlerowicz and Ramachandran said the “point we want to make is about the ambiguity of the experience -- these experiences can be confusing, and it can take time to work out what one wants/needs/desires.”

It’s also “not always clear if/when the mentee might in fact be projecting their own desires onto the mentor (a situation we don’t discuss often but which can pose real pedagogical challenges),” they said.

While “The Erotics of Mentorship” is largely descriptive, it does end with a plea to reframe current campus discussions about faculty-student relationships -- and a question that could keep a team of Title IX administrators busy for a long time.

“The question should not be how to exorcize even the hint of erotic ambiguity from the academic workplace, but rather how to allow our classrooms to remain safe spaces amid such ambiguities; how to support a student’s as yet fluid, and often unself-conscious, identifications and projections without causing these explorations to be manipulated and exploited, or shamed,” they say. “In order to do so, we need to recognize and condemn sexual harassment in an academic context -- and also to acknowledge that, even at our most metaphysical, both we and our students are embodied beings.”

Mixed Reaction

The essay has gotten attention online, some of it complimentary. It’s also been the butt of a few jokes from professors who see teaching as anything but sexy -- and prefer it that way -- along with more serious criticism. While fans have tended to describe the piece as brave acknowledgment of the “natural” attraction between some students and teachers, critics have called it everything from “gross” to a rationalization of abuse of academe’s power dynamic.

Katherine Franke, Sulzbacher Professor of Law and professor of gender and sexuality studies at Columbia University, said Wednesday that while the topic is an “explosive” one that most in academe seek to avoid, “intelligence can be hot.” Power can, too, she said -- wanting someone who has it or having it and being wanted for it.

As for the essay's lingering question about creating a safe space for students, Franke said she was involved in drafting Columbia’s "Consensual Romantic And Sexual Relationship Policy Between Faculty And Students" in 2015. As the first draft reviewed sought to regulate “romantic” relationships only, Franke said she argued for a name change.

“What are romantic relationships?” Franke recalled. “Are we talking flowers and candy? It seemed so quaint, in a Victorian kind of way.” Ultimately, she said, the policy says that "no faculty member shall have a consensual romantic or sexual relationship with a student over whom he or she exercises academic or professional authority.” Instructors who violate the policy by having a relationship with a student they supervise are subject to serious discipline.

“Of course it is inevitable that teacher-student sexual relationships would occur, and I recognize that not all of them are ‘bad for the student,’” Franke added via email. “That said, many are. So I agreed to the policy because I felt it right that as an institutional matter that we create a norm by which the more powerful person is taking most of the risk when entering into a sexual relationship with a student they supervised.”

Brett Sokolow, a campus safety expert and executive director of the Association for Tile IX Administrators, said institutions that apply an outright prohibition on all faculty-student relationships will have “problems of enforcement, problems that zero tolerance of any kind tends to provoke.”

In an ideal world, policies "would prohibit unethical relationships, not relationships by category," as the category — student, professor, staff — itself isn't the problem, he said. That is, an interaction can either be "ethical or unethical irrespective of the categories of those involved."

Beyond policy, Sokolow said the essay's reference to journalist Masha Gessen’s 2017 warning about “moral panic” in The New Yorker also resonated, in that “I hear faculty members saying that they don’t hug anymore, for fear of facing allegations of sexual harassment,” Sokolow said. “We have to find a balance in protecting our employees and students from that which is unwelcome while also respecting their agency to engage in behaviors that are welcome.”

Valerie Sulfaro, a professor of political science at James Madison University who recently, publicly accused a former faculty mentor of harassment after hearing of additional allegations against him, suggested that drawing appropriate boundaries isn’t that hard.

“People see gray areas where there aren't any,” she said. “They're the same place they've always been, and I don't think any decent person would have trouble discerning them. It's okay to tell someone they look nice, it is not okay to tell someone that they look hot, or that they look sexy,” at work, for example.

Similarly, Sulfaro said, dating within academe isn't off limits, but "it's not okay to have a relationship with someone over whom you have power. And I don't think it's ever been okay. It's not that the rules used to be different. It's that people looked the other way when they were broken sometimes, and so some people -- men, mostly -- felt like they were entitled to ignore those rules.”

Judith Shapiro, president of the Teagle Foundation and president and professor of anthropology emerita at Barnard College, called the topic “difficult.” Why? While there “may be something inherently sexy about one partner being stronger, wiser or older, how does one address noxious abuses of power?” she asked.

Shapiro said it’s also important to think about what “forms” erotic behavior takes in particular contexts, the essay's "inspiring examples from other times and places" aside. There's a scene in the 1993 film The Age of Innocence in which Daniel Day-Lewis and Michelle Pfeiffer are riding in a closed carriage and "fall into a state of intense voluptuous intoxication over her bare wrist,” Shapiro said. That's much different than, say, “hooking up in a state of relative drunkenness at a professional conference.” (Ahem.)

And while actual sex is nothing to “belittle,” Shapiro said, equating the sublimation of desire with repression of desire -- as the essay at one point does -- “reflects obliviousness to the fact that we have these two different terms for a reason.”

Corey Robin, a professor of political science at Brooklyn College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, offered a very different take on Twitter, saying the “you’re prudish” and “you’re creepy” camps might be overlooking inherent issues of class.

“The relationship between these discourses of eroticism and sexual harassment are obviously real; I’m not denying it,” he wrote. “I just think we may be missing the hidden discourse of class and that an additional cost of this mooning and yearning sentimentality is that it [needs] to be exclusive and elitist. Because if two lovers is your model of the teacher-student relationship, there’s just not enough love to go around.”