You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

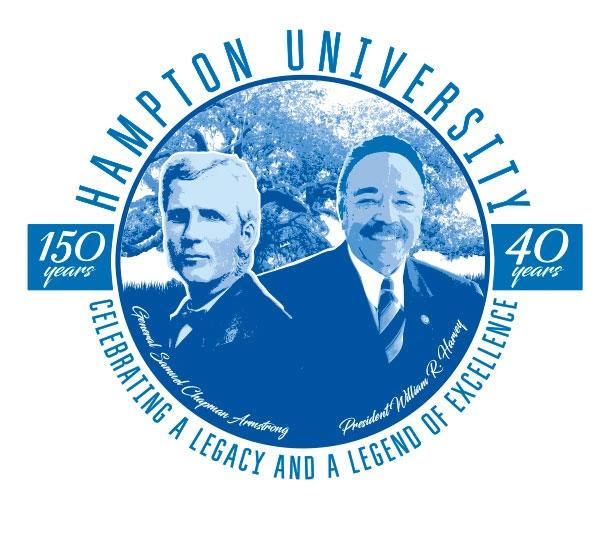

Hampton president William R. Harvey at a Founding Day celebration April 1.

Hampton University

Hampton University spun three celebrations together on the first day of April: Easter, the 150th anniversary of its founding and the 40th anniversary of William R. Harvey’s presidency.

Few leaders in American higher education can compete with Harvey’s four-decade tenure leading Hampton, a private, 4,600-student historically black university on the banks of the Virginia Peninsula across the harbor from Norfolk. The Harvey family has in many ways grown synonymous with the university as it has risen in prominence and prestige.

A leadership institute at Hampton bears the president’s name, and the university’s library is named after Harvey and his wife. Streets on campus were recently rechristened William R. Harvey Way. During the university’s Founding Day celebration on Easter Sunday, the Student Government Association released 40 doves to honor the president, and former university chaplain Michael A. Battle extolled a youthful Harvey’s command many years ago.

A leadership institute at Hampton bears the president’s name, and the university’s library is named after Harvey and his wife. Streets on campus were recently rechristened William R. Harvey Way. During the university’s Founding Day celebration on Easter Sunday, the Student Government Association released 40 doves to honor the president, and former university chaplain Michael A. Battle extolled a youthful Harvey’s command many years ago.

“This young, courageous president not only determined that he was going to stand against the tide of those who wanted to lead us in an opposite direction, but stood up and challenged the faculty and staff of the institution at that time and simply said to them that there is a larger vision for this institution, and if you cannot stand to grow with Hampton, maybe you have a job at the wrong place, and that wouldn’t be a bad time for you to leave if you didn’t have the vision of growth,” Battle said, according to a recording of the event made by a local newspaper, the Daily Press.

Despite the soaring rhetoric, Harvey has faced harsh questions about his leadership in recent months. Students and at least one former faculty member have openly challenged conditions at Hampton, and the Harvey family’s deep affiliation with the university has been tested to a degree rarely seen in the past.

The university took steps to assuage concerns about food quality and dormitory maintenance last month. But students continue to worry that the university is not taking the issue of sexual assault seriously enough, with some feeling uncomfortable because the president’s daughter is the university’s Title IX coordinator. At the same time, a Hampton alumnus and former professor is offering harsh criticism of Harvey’s leadership and his past decisions, which have included building an ambitious and expensive cancer treatment center that has struggled financially.

University leaders say they take student concerns seriously and have acted upon them. Allegations against Harvey are not credible, said the chair of Hampton’s Board of Trustees. Harvey himself said in an interview with Inside Higher Ed that he doesn’t like to “get down in the mud,” referring to the allegations as a “nothingburger.”

Indeed, the Hampton president rejects the idea that the last few months have been difficult for him. He called recent times marvelous, pointing to fund-raising successes for the university, positive local press coverage and his recent receipt of the prestigious John Hope Franklin Award at a March meeting of the American Council on Education. He cites 92 degree-granting programs put in place during his tenure and says Hampton’s endowment has grown by more than 860 percent since he took over.

Yet some students wonder whether the septuagenarian president’s aura of inevitability is cracking.

“There is something going on, bigger picture,” said Arielle Wallace, a senior strategic-communication major at Hampton.

“Hampton’s reputation is what’s perpetuating all of this,” she said. “If the reputation is broken, then change has to come.”

Student Protests

Criticisms spilled into the open Feb. 20, when students raised concerns during a town hall meeting. They were worried about what they saw as poor dining hall conditions, mold in dormitories and what has been described as a culture of insensitivity toward sexual assault on campus.

University leaders responded with a statement detailing Hampton’s procedures for addressing reported sexual assaults and saying administrators take the issues raised by students very seriously. Still, the town hall and university response drew attention on social media. Anonymous users shared stories of sexual assault and harassment through an online service called Curious Cat. An account sharing the stories made 219 posts between Feb. 23 and Feb. 28, although some were comments on previously shared stories instead of new ones, and the university hadn’t necessarily been informed about the incidents. Several days later, a group of students marched across campus to the president’s house, asking for dormitory mold, food quality and campus safety to be addressed. They also asked administrators to be more active in fighting sexual assault on campus. A group calling itself the Independent Collective of Hampton University charged that the university “handles all of its problems by painting over them then telling us [it] is beautiful.”

The university released several additional statements detailing its responses. New hours were put in place for the cafeteria, food options have been expanded and a new dining concept is in place so students can serve themselves, said the most recent news release on the issues, which was posted in March. A contractor inspected residence halls, finding buildings “in very good condition with very limited isolated visible mold activity.” The university pledged to uphold a policy of eliminating mold or mildew within 48 hours.

Students confirmed changes in quality of food service and room maintenance. But some remain unsatisfied, saying they are concerned about rape culture. As at many institutions across the country, they fear a campus climate permissive of sexual assault.

Students confirmed changes in quality of food service and room maintenance. But some remain unsatisfied, saying they are concerned about rape culture. As at many institutions across the country, they fear a campus climate permissive of sexual assault.

Rape culture has become normalized, said Kimberly Burton, a senior political science major at Hampton. Many women don’t feel comfortable reporting sexual assault on campus and might not feel anyone is advocating for them, she said. She has heard repeatedly that students who have experienced sexual assault don’t believe the university will take reports seriously.

“When there’s that culture at Hampton, you’re not going to feel comfortable,” Burton said. “You get interrogated. ‘What were you wearing? What were you drinking?’ The reality is, someone has been mistreated. Someone has been taken advantage of.”

Harvey rejected the idea of such a culture existing at Hampton. In his first year as president, he put in place a sexual assault committee, he said. It is made up of five people -- three women and two men. A woman has always been the chair. The university has also participated in campaigns to raise awareness and educate students about sexual assault.

“There clearly is no rape culture at Hampton,” Harvey said.

“I understand the climate and culture we are in, and sometimes people just don’t take the time to try to get at the truth,” Harvey continued. “One of the things we try to do is not to deal in falsehoods, rumors and gossip, but deal with the truth. The fact is that we have taken this seriously for a very long time, and we’re going to continue to take it seriously.”

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights started an investigation of Hampton in August for potential violations of Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 related to sexual violence. University officials say the investigation is related to a complaint a woman who was not a student lodged against a Hampton student several years ago.

The case was investigated by a former Title IX coordinator at Hampton and heard by the university’s Sexual Discrimination and Misconduct Committee in 2014, administrators say. The committee did not find a preponderance of evidence to support the claim against the student, and a university administrative appeals committee upheld that finding. The university maintains it fully followed appropriate policies and procedures and that it has cooperated with the federal investigation.

Hampton officials have repeatedly stressed that students need to report assaults.

“The way that it works at Hampton is that the Title IX office as well as the police department -- that is the Hampton University Police Department -- work in tandem to ensure that we respond,” said JoAnn Haysbert, the university’s chancellor and provost. “First and foremost, a student has to report any allegations.”

The university’s most recent available annual security report lists several incidents of sexual violence that have taken place on or near campus. Most were reported in 2016, the most recent year for which data has been released.

Two rapes were reported on main campus property in 2016, one was reported at on-campus student housing, and one was reported on noncampus property, according to the report. One instance of fondling was reported on main campus property. Dating violence on campus property was reported three times, and dating violence at on-campus student housing was reported twice.

Dating violence is defined as a person being threatened or subjected to physical or sexual violence by someone with whom they have shared a close romantic or intimate relationship.

No rapes or instances of dating violence are listed in the report for 2015 or 2014. One case of fondling was reported in 2014. As is typical, the report does not include information on how any of the cases were resolved.

Students have raised questions about the university’s Title IX coordinator, Kelly Harvey-Viney. She is President Harvey’s daughter, which has prompted worries she could be caught between protecting the reputation of her father’s university and acting in students’ best interest.

A Family Affair

A president’s daughter serving as Title IX coordinator does not automatically create a conflict of interest, said Erin Buzuvis, a professor at Western New England University School of Law and co-founder of the Title IX Blog. A conflict of interest could theoretically arise if the president himself were to be under investigation for Title IX-related issues and his daughter supervised the investigation, or if the president used his authority to protect his daughter’s job, she said.

Whether a president’s daughter can be an effective Title IX coordinator is another question. If students don’t feel they can report assaults to a Title IX officer, the situation needs to be addressed, Buzuvis said via email.

“The thing about conflicts of interest is that most professionals take seriously not only actual conflicts, but the appearance of conflicts as well,” she said.

Harvey-Viney is “imminently qualified,” said Haysbert, Hampton’s provost and chancellor.

“We have never had an attorney in that office before,” she said. “We’ve had some qualified people. By far, Kelly Harvey is the most qualified we’ve had.”

Hampton’s vice president and general counsel, Faye Hardy-Lucas, also supports Harvey-Viney. The Title IX office reports to Hardy-Lucas, so there is no conflict of interest, Hardy-Lucas said in a recent letter to the president of the National Hampton Alumni Association. The letter was an answer to a list of concerns that had been emailed by an alumna. Hardy-Lucas has never seen more thorough investigative reports than those compiled by Harvey-Viney, she wrote.

“To stress how thorough the investigative reports are, I have indicated to Dr. Harvey-Viney that ‘you do not have to be that thorough,’” Hardy-Lucas wrote.

Harvey-Viney’s stint as Title IX coordinator is far from the only instance of a Harvey family member being employed by the university or closely tied to it. Both of the president’s daughters have worked for the university at different times in their lives, and he has a son-in-law and daughter-in-law who currently hold university positions. Also, his son is an executive vice president at a construction and development company that has annually been one of the university’s largest contractors.

Harvey-Viney’s time working for the university can be traced back to 2003, when she started teaching broadcast journalism classes at Hampton’s Scripps Howard School of Journalism and Communications. She had been a reporter at a local television station, WTKR-TV, until she resigned in 2003.

In 2000, the station suspended and demoted her after she ran afoul of a conflict-of-interest clause in her employment contract. She made a $1,000 contribution to then Senator Chuck Robb’s re-election campaign, which she had been reporting on as an anchor. Her father was raising money for Robb and suggested she make a contribution, she told the Daily Press at the time.

In 2005, she left her job as a Hampton professor to attend law school at the University of Pittsburgh. Today, Harvey-Viney is listed as the director “setting the agenda” for the university’s Center for Public Policy, in addition to her position as Title IX coordinator.

Harvey’s other daughter, Leslie Cash, is married to Ataveus Cash, a former Hampton University quarterback who is assistant director for operations in the university’s athletics department. Leslie Cash also staffed Hampton’s Washington office as of September 2015, documents show. Haysbert confirmed Leslie Cash works at the office.

W. Christopher Harvey is the Hampton president’s son. In 1999, he married Valerie Harvey, a dermatologist who is currently listed as a Hampton University adjunct faculty member. She is also co-director of the university’s Skin of Color Research Institute.

Of greater note, Christopher Harvey is an executive vice president at Armada Hoffler Construction, a branch of a publicly traded development company. He joined the company in 2002. Armada Hoffler has been listed on tax forms as one of Hampton University’s top contractors in 10 out of 11 years from 2006 to 2016. The university paid the company at least $132.5 million during that time.

Armada Hoffler recently built a multimillion-dollar proton therapy institute for Hampton University. The university is also the company’s second-largest office tenant, paying just over $1 million in annualized base rent, according to Armada Hoffler’s most recent annual report. That’s 5.3 percent of Armada Hoffler’s office rent portfolio and 1.1 percent of its total rent portfolio.

In 2011, before it became a publicly traded company, Armada Hoffler “partly donated” to Hampton University a tower known as Harbour Centre, the Daily Press reported at the time. Hampton also paid an undisclosed sum in cash toward the building, the newspaper reported. Hampton’s recent financial documents list the 14-story building as having been acquired by donation and representing about $21 million in assets.

Hiring a family member or doing business with a firm where a relative is employed doesn’t necessarily constitute nepotism, experts say. A university can fairly hire a president’s relative if it follows an established hiring process, evaluates multiple candidates’ credentials and ultimately picks the most qualified person for a position.

Organizational behavior must be evaluated, said Robert Jones, a professor of psychology at Missouri State University and a nepotism expert.

“In organizational psychology, we look for consistent and reliable patterns,” Jones said. Organizational behavior and consistently hiring family can suggest a pattern, he said.

Hampton’s Board of Trustees is aware that members of the Harvey family hold different positions at the university, said Wesley Coleman, board chair. Harvey-Viney takes her job seriously, has the right background and does not report to her father, Coleman reiterated.

“There are levels between her and the president,” Coleman said. “She doesn’t go and run to him or have to report to him what she’s doing. So that’s not an issue.”

Christopher Harvey has not been involved in Armada Hoffler’s projects with the university, Coleman continued. When the company makes a presentation to the board or is a finalist for a bid, the university president openly discloses his son’s employment at the construction company.

“That is one, I can assure you, the board is fully aware of and has been assured there is not anything inappropriate going on,” Coleman said. “They still do competitive bidding. They aren’t just awarded projects without due diligence.”

Christopher Harvey echoed that, saying in a phone interview that he has worked for Armada Hoffler for 15 years but has nothing to do with Hampton. Asked whether there have been any projects he would have overseen if he did not have a connection to Hampton, he said that isn’t his role at the company.

Christopher Harvey oversees a joint venture created to develop hotel and hospitality projects, according to the Armada Hoffler’s website. He has previously been director of business and hotel development, development coordinator, and project engineer. Earlier in his career, he worked for Pepsi-Cola of North America, published records show.

Hampton has not sought to cover up the fact that it hires members of the Harvey family. For instance, statements filed in its IRS form 990s have said the university is open to hiring employees’ family members. Take a statement from 2005:

“The university has a policy on employment of relatives and has welcomed the hiring of family members to its staff (i.e. spouses of other employees, and employees’ children working in summer programs, etc). To ensure that there is not a conflict of interest in employment, the university does not place any employee in a position that would directly or indirectly, supervise or influence a related employee’s rate of pay, promotion or handling of confidential information. Supervisors and administrators consider each employee, or potential employee on the basis of personal merit, qualifications and skills.

The statement went on to note that the president’s wife, Norma Harvey, was paid $31,685 in the fiscal year ending in June 2005. The pay was for services she provided as the university’s first lady and to benefit the university, it said.

The statement went on to note that the president’s wife, Norma Harvey, was paid $31,685 in the fiscal year ending in June 2005. The pay was for services she provided as the university’s first lady and to benefit the university, it said.

It’s relatively common for colleges and universities to pay presidential spouses if they perform specific duties. However, leaders have found themselves in hot water after arranging favorable employment situations for other family members.

Recently, the new chancellor of Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, Carlo Montemagno, was accused of nepotism after he negotiated jobs for his daughter and son-in-law when he was being hired. In February he said he would pay back university-provided relocation funds he used to pay for his daughter’s household to move. The university also launched ethics reviews. Montemagno remains chancellor.

In 2016, then University of California, Davis, chancellor Linda P. B. Katehi was placed on administrative leave amid concerns that her daughter-in-law received more than $50,000 in pay increases over two and a half years and that the program employing Katehi’s son had been placed in her daughter-in-law’s department. Katehi resigned months later after the UC system found she had violated multiple university policies and exercised poor judgment. Her lawyer said the investigation found no violations in the areas of nepotism, conflicts, personal gain or financial mismanagement of funds.

Norma Harvey has regularly been paid by Hampton for her duties as first lady, a review of Hampton’s tax documents shows. She was paid $40,000 for the year ending in June 2016, the most recent for which documents are available. That was up from $30,000 the year before.

Her husband also received more from the university in 2016 than in 2015. President Harvey’s compensation totaled $889,384 for the year ending in June 2016, up from $828,420 the previous year. His base compensation rose to $432,858 from $416,150, with the rest coming from nontaxable benefits and deferred compensation.

President Harvey’s total compensation more than doubled over a decade. He received $259,728 in compensation and $52,725 in benefits and deferred compensation for the year ending in 2006.

The Harveys have donated well over $3 million of their own money to the university, it has said.

Hampton hires for talent, according to the president.

“All you have to do is look at the facts, not look at what, perhaps, some disgruntled person might want to say,” Harvey said. “It doesn’t make any difference whether or not it’s a man or a woman, young or old, black or white, gay or straight. If the person has talent and there is a vacancy and they want to be a part of a very dynamic, world-class university, they will be hired. And that’s the case with my family members. Now, I’m also aware of the fact that, with family members, there is a need to make sure that there is no conflict. So that’s always 100 percent reported to the board.”

An Attack on Leadership

Alleged nepotism is just one of several issues targeted by a man who has taken eye-opening steps to criticize Harvey in recent months: William E. Lewis.

Lewis graduated from Hampton in 1976 and taught there for nearly eight years, starting in 2010, before he was fired several months ago. He was an adjunct professor and acting pre-law adviser at Hampton late last year when he wrote an explosive letter containing a long list of allegations against Harvey. The letter has circulated on social media. It is often raised by Harvey’s critics, with some pointing to specific allegations, like nepotism, and others saying the letter touches on some issues, like finances, that need further exploration.

It was written as a response to a letter Harvey penned early last year criticizing The Quad, a television show about a fictional historically black university. Lewis addressed his response not to Harvey but to Debra Lee, chair and chief executive officer of BET, the network on which the show runs. But Lewis says he hand delivered a copy to Harvey’s office.

Much of what Lewis wrote is criticism of Harvey, accusations and rumors about him, and allegations of poor conditions at the university.

That includes questions about financial problems, the state of the Hampton University Proton Therapy Institute, the state of the university’s physical plant and an argument that the university’s Board of Trustees has failed to oversee its administration. Lewis also complained of nepotism, depressed faculty and staff salaries, and suppression of student free speech, among other issues.

Lewis called for leadership change at Hampton. He wrote, “It’s obvious that Harvey and everyone in his Administration needs to stepdown [sic] IMMEDIATELY!!”

Lewis delivered the letter, dated Nov. 1, and taught a constitutional law class the next day, he said. He was terminated Nov. 6.

Days later, Lewis and his daughter, a Hampton graduate, were banned from the Hampton University premises, Lewis said. Hardy-Lucas confirmed the bans, saying employees who are terminated for cause are routinely banned from campus and that university police banned Lewis’s daughter after receiving information stating she was posting threatening information on social media. Lewis has written that he was baffled after his daughter was served with a no-trespassing order and referred to her ban as collateral damage.

Lewis was terminated for using the Blackboard course management system to promote a “personal agenda” not related to course instruction, according to the termination letter the university sent him. The termination letter quotes Lewis as posting an announcement saying he had “bitched and moaned for years over how to address a very sore spot as it regards my alma mater and the Harvey administration,” and Haysbert said he sent his letter to students using Blackboard. University lawyers also sent Lewis a cease-and-desist letter on Nov. 8. It demands Lewis stop making “further threats” against Harvey, stop publishing “false and defamatory statements,” and take steps to remove his letter from social media.

The next month Lewis circulated a newsletter containing personal attacks on Harvey. It used a pejorative term to refer to the president and continued to make serious allegations against him.

“And now, with [Harvey’s] daughter as the Title IX Coordinator, and the [Hampton University] Police Department serving as [Harvey’s] personal Gestapo, how can our children, our students, and women feel safe?” Lewis wrote.

Lewis will continue to pressure the Board of Trustees to make a change, he said in an interview. He believes Harvey has operated unchecked for too long.

“He doesn’t have to worry about anybody else,” Lewis said.

Lewis doesn’t fear being sued. He said he’s planning his own lawsuit for wrongful termination and wants to face off in a courtroom with Hampton and Harvey.

“If he’s going to sue me, how much more do I have to do before he comes to get me?” Lewis said.

Hampton’s general counsel, Hardy-Lucas, said Lewis was suspended from practicing law in Louisiana in 2009 after handling cases inappropriately. In November, she wrote a letter to Hampton’s administrative council saying the university must conduct more thorough background checks before hiring faculty and staff.

There are no plans to sue Lewis, Hardy-Lucas says.

“At this point, we don’t want to lower ourselves to that point and give him more of a public platform,” she said. “Why should we spend our time trying to go after someone? We wouldn’t get anything from him, and that’s what he wants. So we’re not willing to, at this point.”

Lewis responded that he is troubled his name has to be sullied because he asked questions. He acknowledged being suspended from practicing law in Louisiana for two years, saying he refused to take a private reprimand in a complex case involving clients lying.

“That doesn’t have anything to do with what I say in 2018,” Lewis said. “The thing they try to do is discredit me.”

Hampton’s treasurer and vice president for business affairs, Doretha J. Spells, wrote a letter to Lewis in November calling his statements untruthful. She wrote favorably of the university’s cash-management practices, creditworthiness, business enterprises and financial stability.

Lewis’s letter is inaccurate, President Harvey said.

“I’m saying to you that it’s a nothingburger,” Harvey said. “He sent his diatribe to everybody. You’re the only one that’s responding.”

Harvey does not know Lewis and could not identify him, the president said, and local newspapers have not given Lewis attention.

“They know that it’s rumor,” Harvey said. “They know it’s gossip. They know it’s lies. And that’s unfortunate, quite frankly. But I’m glad that nobody else has taken it up, because it’s one somebody that’s leading the charge, and I will say to you I have absolutely no idea why. I don’t know him. If he were to walk into my office with three other people right now, and somebody said, ‘I’ll give you $100 trillion if you could identify him,’ I couldn’t get a penny.

“I never had a cross word with him,” Harvey continued. “And I don’t get down in the gutter with him or anybody else. So I have not responded. There have been others that have responded. I don’t intend to respond, to you or to anybody else who thinks that this is a story, because it isn’t.”

Asked about the student protests, Harvey said they were mild. He was proud of the order and structure students used to express their concerns.

Harvey started meeting with student leaders 40 years ago, he said. He has been holding town hall meetings with students for 30 years.

“See, these things don’t get into print because it doesn’t fit the narrative,” Harvey said. “I believe strongly that people who have to live with decisions ought to have input into the decision-making process.”

A President’s Successes

While Lewis has thrown inflammatory charges at Harvey, university officials have publicly and repeatedly praised him.

A trustee told the Daily Press in February that the board stands back, letting Harvey lead as he wants.

A trustee told the Daily Press in February that the board stands back, letting Harvey lead as he wants.

“He asks his trustees to let him run the school and do what he needs to do to run the school and the day-to-day thing and to focus on the big issues,” Buddy David told the newspaper, which described him as a trustee and longtime friend of Harvey’s.

Trustees are invited to address “big ideas or other things they want,” but they do not get in the weeds, David said.

The newspaper also quoted the dean of Hampton’s journalism school -- who is also the university’s assistant vice president for marketing and media -- calling Harvey “fierce, formidable but amazingly fair.”

Hampton has grown in many ways under Harvey’s leadership. About a decade into his presidency, in 1988, the university had roughly doubled enrollment to about 5,000, increased its faculty count from 200 to 350 and grown its endowment from $29 million to $76 million. It was operating on budget after running a deficit every year between 1972 and 1979.

The university was practicing zero-sum budgeting, requiring every budget item to be justified each year, The New York Times reported in 1988. Quarterly budgeting requirements were a significant cost control requiring department heads to frequently justify purchases.

“You must run a college or university like a business with an educational objective,” Harvey told the Times. “What we’ve tried to do is run Hampton like a business.”

Freshmen with high test scores and undergraduates with high grade point averages were given tuition rebates. Those qualifying for Hampton’s honors dormitory paid lower rent and had access to amenities like a swimming pool. Faculty members publishing in peer-reviewed journals were offered $1,000 incentives, and the university also had financial incentives for those who wrote the most book reviews in local newspapers.

Several prominent corporate leaders had served on Hampton’s board. Harvey was also given credit for bolstering Hampton’s development efforts. The university had opted out of the UNCF in the 1960s, before Harvey’s tenure, giving it control of its own fund-raising.

By many accounts, Hampton’s financial strength has grown since then. The university publicly launched a campaign in October to raise $150 million. Its endowment grew to $279 million as of the end of the 2017 fiscal year. In July, it will move from the Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference to join the Big South Conference, a move that could raise the university’s profile while cutting travel time and expenses.

The university has a strong financial profile, according to its most recent debt rating from S&P Global Ratings, issued in May 2017. S&P assigned Hampton bonds an A rating, an upper-medium investment grade attractive to investors.

Hampton runs consistent surpluses, spends its endowment conservatively and draws revenue from a diverse set of sources, S&P found. The university posted an $8.3 million surplus in the 2016 fiscal year, even after its proton therapy institute lost money.

Only 61 percent of revenue came from tuition and auxiliary revenue, and 23 percent came from grants and contracts in 2016. Hampton draws a majority of its students from outside the state, giving it good geographic diversity, S&P wrote.

For 2016-17, the university listed the total cost of attendance at $34,676 for a student living on campus, including room and board.

The university’s enrollment had fallen by about 1,000 students over five years as of the fall of 2015, S&P found. But it was rebounding in 2016 due in part to a large freshman class. Enrollment hit 4,395 students on a full-time-equivalent basis.

S&P did note that Hampton’s board approved a one-time $25 million draw on its endowment to pay for capital projects and to fund new programs. It also said the university’s freshman matriculation rates fluctuated recently, and that it carries a relatively high debt load -- $187 million outstanding as of 2016. Debt-service costs were front-loaded, meaning they will decline over time.

The construction of the proton therapy institute contributed significantly to Hampton’s debt load. S&P said the center was a new enterprise bringing business risk.

Proton Therapy Questions

The Hampton University Proton Therapy Institute was called the largest free-standing center of its kind when it opened in 2010. Hampton built it despite not having a hospital and medical school -- a rarity in the tiny but growing world of proton therapy, where many providers are tied to large research universities with medical centers.

It’s expensive to build facilities to treat patients using proton therapy, a technique using a concentrated beam to target cancerous tumors with more precision than other treatments. Hampton’s proton therapy institute cost more than $200 million to build and equip, and the university financed the project largely with debt.

Leaders had projected the institute could treat as many as 2,000 patients per year, according to the Daily Press. But it struggled to find its footing in early years, treating only about 250 patients per year between 2010 and 2015.

Harvey strongly defends the proton therapy institute, saying it eases human misery and saves lives. Today, the institute treats some 55 patients a day with various types of cancer, he said. It is not losing money on an operating basis, he added.

“We are operating in the black and we are paying back the debt from some of the profits over the operating costs, which is how businesses work,” he said. “Hell, people don’t understand that. You find AT&T or anybody else, they may buy a business. It may take 10, 12, 15 years to pay it off. But they look at the debt, they look at the margin, they look at the operating costs.”

In the past, Hampton’s leadership told the finance world that the moment when revenue from the institute would surpass its expenses was just around the corner. Yet a close examination of Hampton’s audited financial statements shows the institute has been unable to generate enough in net patient service revenue to cover its total program expenses in the past.

The university’s administration told S&P positive operating performance was expected at the proton therapy institute in 2017. But the center lost $2.99 million that year, Hampton’s audited financial report for the year shows.

As of 2014, the institute had been operating with net losses since opening, according to documents from bonds issued that year. But it expected losses to shrink and revenue to exceed expenses starting in the 2015 fiscal year, those documents state.

The institute lost $3.3 million in 2015. It lost $2.38 million in 2016.

Nonetheless, the center’s losses have narrowed from earlier years, when expenses sometimes outpaced revenue by more than $10 million.

Lewis, commenters on social media and alumni speaking to Inside Higher Ed off the record have voiced concerns about the proton therapy institute’s finances. Harvey said alumni do not look at Hampton’s books. They likely do not understand the finances associated with the institute, he said.

“Anybody that knows anything about the finances of the proton center can’t say that,” he said. “And because they’re an alumnus -- come on, man, you should know better than that. Alumni don’t know what’s going on at Harvard, George Washington, Hampton.”

Proton therapy has long been haunted by worries about cost and coverage by insurers. Proton therapy centers can be dozens of times more expensive to build than facilities offering traditional radiation therapies. Some analysts and health-care experts worry the market for proton therapy is near its saturation point as new centers come online, leaving some organizations at risk of defaulting on bonds, Bloomberg reported. Now, many medical providers building proton therapy centers are trying to minimize risk by limiting the size of facilities.

Insurers have in some cases balked at proton therapy, saying there is not enough research to support a treatment that can be more expensive up front than traditional radiation treatments. Physicians have sometimes been skeptical of its relative benefits as well.

Against that background, Hampton might seem to be stuck with the bill for a 98,000-square-foot institute just as competitors are coming online with smaller operations requiring less up-front investment. The National Association for Proton Therapy has 28 members operating proton therapy centers. It counts another nine centers under construction and 15 more in development.

But some argue Hampton may have picked the right time to invest in an emerging technology.

Medicare covers proton-beam therapy, providing a large payer. Hampton’s proton therapy institute drew about 40 percent of its revenue from government reimbursement programs like Medicare and Medicaid as of 2014. The university was also working to boost referrals from physicians.

Hampton has been pressing state lawmakers to pass legislation expanding access to proton therapy. Last year it accused insurers of violating a state law designed to give patients a chance of being treated by proton therapy. The leader of a state trade association for insurers replied that Hampton was trying to stretch the law to force insurers to pay for treatment.

The university’s proton therapy institute also serves a region and populations that otherwise do not have widespread access to the treatment, said Scott Warwick, executive director of the National Association for Proton Therapy. Patients often do not want to travel for cancer treatment, he said.

“African-American men have a higher percentage of instances of prostate cancer,” Warwick said. Hampton is “able to serve that population, which I think is definitely a positive.”

Hampton can also perform research at the proton therapy center.

“It’s a great outlet for them to be involved in clinical research,” Warwick said. “That’s great for students, it’s great for the university and it’s great for proton therapy.”

Harvey makes an emotional argument for battling cancer.

“It touches everybody,” he said. “It’s either you’ve got it, a family member has it, a neighbor has it, a friend has it, a colleague has it -- somebody that you know has had cancer. And we are doing something about it.”

Echoes of the Past

Recent criticisms of Hampton and its finances, cafeteria operations, and alleged censorship echo those from the past. During his decades-long presidency, Harvey has been heavily involved in his own business ventures, which included becoming owner of a Pepsi bottling plant in Houghton, Mich., in 1986.

At the time, Roger Enrico, Pepsi’s president, sat on the Hampton University board. Harvey’s wife was on the Houghton bottler’s board.

The acquisition didn’t sit well with Roy Hudson, who had been president of Hampton from 1970 to 1976.

“I see this as a real conflict of interest for an educator and a scholar,” Hudson told The New York Times. “It would have been an excellent opportunity for the school of business to own the franchise, instead of feathering one’s own nest.”

Harvey responded by insinuating Hudson didn’t understand franchise agreements, saying he saw no conflict of interest because Hampton was not in his franchise’s territory. Pepsi wanted more black owners, Harvey said.

“Blacks are a nation of consumers and we don’t produce very much,” Harvey said, according to the Times. “It’s an excellent opportunity for me to make some money and to serve as a role model.”

In 2003, Hampton found itself the center of controversy over both censorship and its cafeteria. The university’s administration reportedly confiscated copies of the university’s student-run newspaper, The Hampton Script, when it did not have a letter from the university’s acting president on the front page.

The Script was running a front-page story about the university cafeteria passing its latest city health inspection and being able to remain open after earlier inspections showed numerous code violations that had gone uncorrected for months. Haysbert, who at the time was Hampton’s acting president while Harvey took a sabbatical, had asked the newspaper to print on its front page a letter she wrote detailing ways the university acted to fix problems. The letter also criticized the media for focusing on Hampton when other universities had issues as well, the Daily Press reported.

The edition was ultimately republished with Haysbert’s letter on the top half of the front page. The front page also contained the original cafeteria story and a description of the confiscation of newspapers.

Hampton has been the center of cultural controversies at various other times in Harvey’s presidency. Its dress code has often been a source of tension with students, and several years ago its business school dean defended a policy prohibiting dreadlocks and cornrows for male students in an M.B.A. program, arguing the hairstyles are not businesslike.

Hampton has been the center of cultural controversies at various other times in Harvey’s presidency. Its dress code has often been a source of tension with students, and several years ago its business school dean defended a policy prohibiting dreadlocks and cornrows for male students in an M.B.A. program, arguing the hairstyles are not businesslike.

In 2005, students were accused of violating university policy by handing out fliers about Hurricane Katrina, homophobia and some other issues. Days later, a controversy erupted over whether staffers had placed a moratorium on new student organizations after a group attempted to create a gay-straight alliance. At the time, the leader of the group called Hampton an “extremely conservative school concerned about its image” and noted President George W. Bush had appointed Harvey to the board of government-sponsored mortgage giant Fannie Mae.

The controversies date back further. In 1991, some students concerned about civil rights policies protested during Hampton’s commencement as then President George H. W. Bush received an honorary degree.

Succession Planning

Hampton is currently advertising an anniversary gala at the end of April in Harvey’s honor. A poster for the event includes a seal the university has been using of late. It bears the likeness of Harvey and Hampton’s founder, Samuel Chapman Armstrong, marking Hampton’s 150th anniversary and Harvey’s 40th year as president.

Hampton is currently advertising an anniversary gala at the end of April in Harvey’s honor. A poster for the event includes a seal the university has been using of late. It bears the likeness of Harvey and Hampton’s founder, Samuel Chapman Armstrong, marking Hampton’s 150th anniversary and Harvey’s 40th year as president.

But Harvey gives no indication he plans to become a past president soon. He has thought about retirement, he said. But the topic is between him and his Board of Trustees.

“The fact is that I am 77,” Harvey said. “I don’t mind telling people how old I am. I probably have more energy than a 27-year-old.”

Every single day brings something new, Harvey said. On a recent Friday, thousands of high school students visited Hampton’s campus. Harvey met several students whose parents had graduated from the university.

“Well, I hugged them and talked to them about where they’re from, asked them what their major is going to be,” Harvey said. “I enjoy that kind of thing.”

The idea of retirement is not unsettling, Harvey said. He thinks he has five or six books to write. A 2016 book he wrote, The Principles of Leadership: The Harvey Leadership Model, was recently published in China.

While the president has little to share about retiring, he is willing to discuss the topic of leadership. That includes succession planning, a practice Harvey picked up from serving on corporate boards. He holds a succession-planning session with Hampton’s Board of Trustees every other year. The session covers the president, vice presidents, deans and department chairs so Hampton will have a plan in the event anyone leaves.

Several key members of Harvey’s administration have been at Hampton nearly as long as he has. Haysbert joined the university in 1980, as did Spells, the treasurer and vice president for business affairs. Hardy-Lucas, the general counsel, has held that position since 1994.

Harvey casts himself as the team leader.

“I cannot stress this enough,” he said. “It is the team that has made Hampton as great as it is, and I am the team leader. I’m a strong team leader. I’m a very good manager. I emphasize management and I don’t apologize for that. My board knows that, my officers know that, and I think that is one of the reasons that Hampton continues to excel.”