You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

For the last few years, community colleges have seen an increase in pressure to focus more on career and training education.

The two-year institutions are being asked for more certificates, apprenticeships and other nondegree credentials that will push students into skilled professions quicker. Last week, President Trump stressed the need for more vocational schools and suggested that community colleges change their names and shift their focus to offering mostly work-force programs.

But there's another side of the community college coin that doesn't receive as much acknowledgment from policy makers -- transfer.

"The bottom line is that we need community colleges to align their programs with job opportunities," said Josh Wyner, executive director of the College Excellence Program at the Aspen Institute. "But that pathway is often through a bachelor's degree program."

The Alamo College District in Texas, for instance, has started a new effort with Texas A&M University to answer the state's demand for engineering graduates. The community college and the university are encouraging students to start their engineering careers at Alamo as a way to save money on tuition.

Community colleges may not be the obvious route to a four-year degree to some observers, but in states like Florida and California, the transfer role is essential to the states' ability to produce bachelor's degrees. And they particularly help minority and low-income students earn bachelor's degrees.

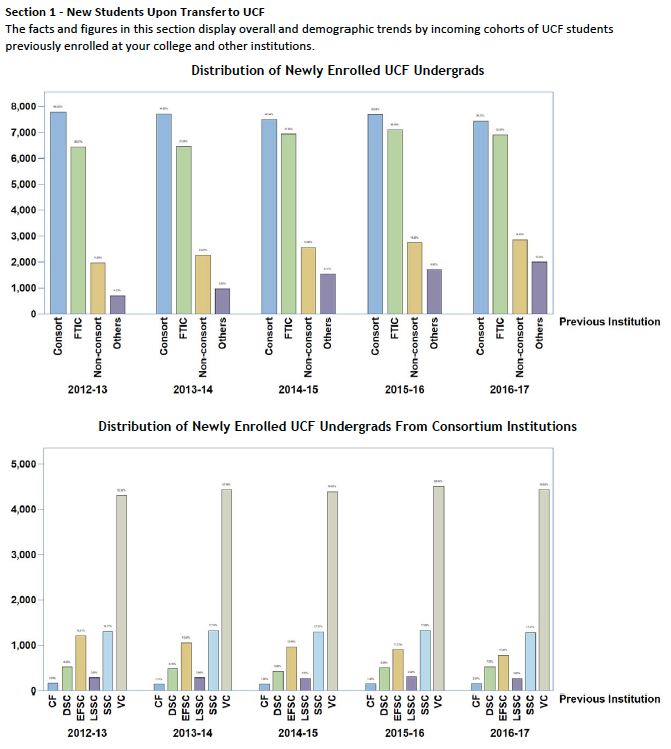

Take, for instance, the University of Central Florida, where the number of students -- nearly 8,000 -- transferring to the institution from a consortium of five community colleges was larger than the number of first-time college students, who numbered about 7,000 in 2016.

The relationship between the community colleges and the university is more apparent when examining the majority of those transfer students to UCF who come from neighboring Valencia College in Orlando, which sent more than 4,000 students to the university last year.

"One of the really powerful things about community colleges is they offer conduits to students who don't start at four-years," Wyner said.

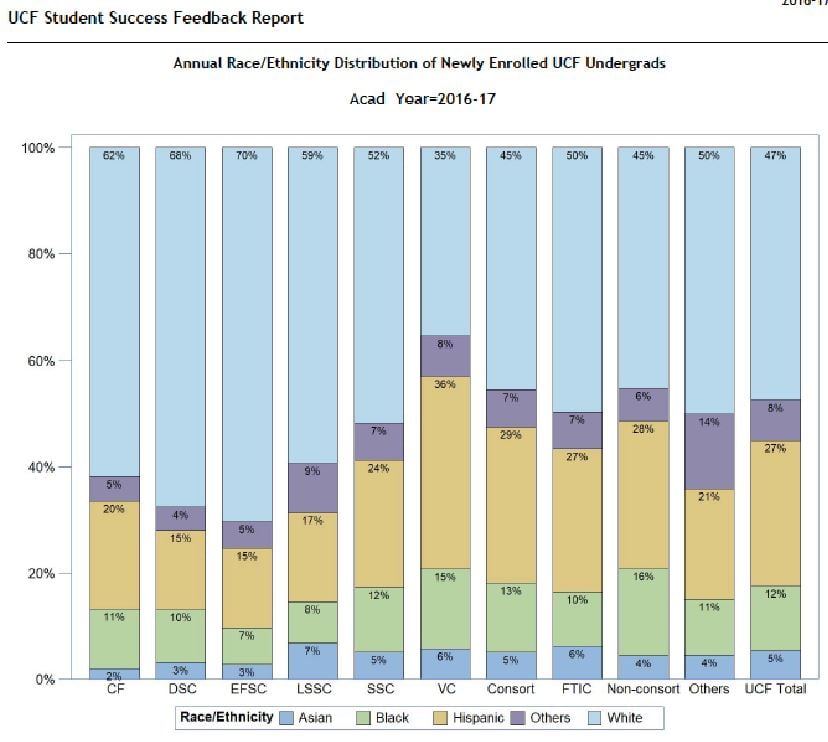

The majority of first-generation, African-American, Latino and Native American students start at community colleges, because of their affordability and open-access missions, Wyner said.

"If we suggest community colleges are only avenues to career and technical education, we're shutting off low-income and students of color from pathways to a bachelor's degree," he said. "Those are growing populations in our country and we have to activate that talent in career and technical and bachelor's and beyond. If we cut off that avenue, we'll deepen inequities nationally."

In the Orlando area, a significant number of black and Hispanic transfer students enrolled in UCF from Valencia College last year. Thirty-six percent of UCF's Hispanic students transferred from Valencia compared to 27 percent of Hispanic students last year for whom UCF was their first time in college, according to Valencia.

"Community colleges don't always do a great job and they do need to get better," Wyner said. "But they've been important engines of mobility, and part of the way they've done that, and that's what happened in Orlando, is by providing the first two years of the bachelor's degree."

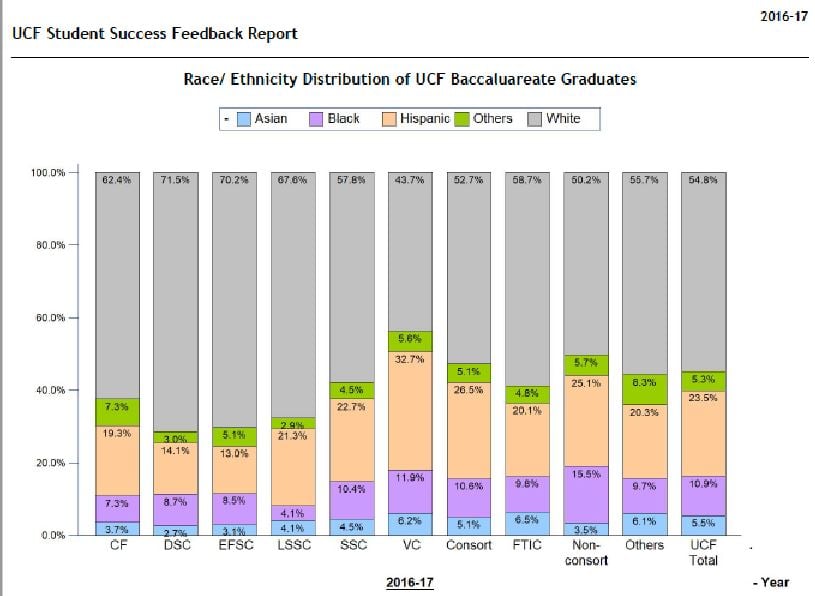

Joyce Romano, vice president for educational partnerships at Valencia, said the college's role in guiding students from the two-year institutions, onto a transfer pathway and into the university doesn't end there. These students are graduating and entering the fields that are in demand for the region -- like business and health care, she said.

Davis Jenkins, a senior research scholar at the Community College Research Center at Columbia University's Teachers College, said that politicians and some academics have created a false dichotomy between transfer and career and technical education. For one, 60 percent of degrees are in occupational fields, and liberal arts graduates do well in the labor market if they have technical skills, he said, adding that researchers are also seeing diminishing returns on certificates.

For instance, a short-term certificate may take a year to complete and lead to a $12-an-hour job, but people would rather work at a big-box retail store for $11 an hour, he said.

"Increasingly people need baccalaureates, and for most people, it's an applied work-force baccalaureate," Jenkins said. "You can't have career and technical education and academic transfer separate. They need to be together."

Employers have shifted to wanting a more highly automated work force with bachelor's degrees as the technology has advanced, not because a bachelor's degree indicates a certain class status, he said.

"There is a challenge to higher education that's really profound, but it's not that we need to go back to narrow skills training," Jenkins said.