You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

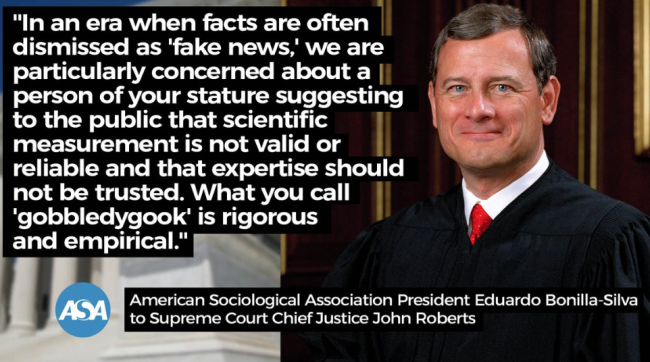

When you come for the social sciences, you’d better come correct. That’s what the president of the American Sociological Association telegraphed to U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts this week, in response to Roberts’s recent reference to social science data as “sociological gobbledygook.”

In an era when “facts are often dismissed as ‘fake news,’ we are particularly concerned about a person of your stature suggesting to the public that scientific measurement is not valid or reliable and that expertise should not be trusted,” Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, president of the association and a professor of sociology at Duke University, wrote to Roberts in an open letter. “What you call ‘gobbledygook’ is rigorous and empirical.”

Roberts’s jab at sociology came during Oct. 3 oral arguments in the high-court case Gill v. Whitford, which relates to partisan gerrymandering in Wisconsin. Paul M. Smith, a lawyer for the appellees, a group of state Democrats opposed to what they deem to be excessively partisan drawing of electoral districts, argued that “this is a cusp of a really serious, more serious problem as gerrymandering becomes more sophisticated with computers and data analytics and a -- and an electorate that's very polarized and more predictable than it's ever been before.”

Smith added, “If you let this go, if you say this is -- we're not going to have a judicial remedy for this problem; in 2020, you're going to have a festival of copycat gerrymandering the likes of which this country has never seen.”

In his eventual reply, Roberts said that “the whole point is you’re taking these issues away from democracy and you're throwing them into the courts pursuant to, and it may be simply my educational background, but I can only describe as sociological gobbledygook.”

Later, Justice Stephen Breyer echoed Roberts when he asked, “Can you answer the chief justice's question and say the reason they lost is because if party A wins a majority of votes, party A controls the Legislature. That seems fair. And if party A loses a majority of votes, it still controls the Legislature. That doesn't seem fair. And can we say that without going into what I agree is pretty good gobbledygook?”

Both the phrasing and the sentiment were perhaps surprising for Roberts, a Harvard College alumnus who majored in history, which straddles the humanities and the social sciences. In any case, the idea of sociological data as “gobbledygook” annoyed a number of academics, who took to Twitter in rebuke. Some pointed out that data on gerrymandering was political science, not sociology.

In an op-ed for The Washington Post, Philip Rocco, an assistant professor of political science at Marquette University, wrote that Roberts's comment suggested that Americans don't trust a judicial decision based on social science. But Roberts's questions "downplay how social science has helped the court understand complex and historically significant issues," he said. In the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education opinion, for example Chief Justice Earl Warren relied heavily on social science research by Kenneth Clark to refute the Plessy v. Ferguson doctrine of “separate but equal."

More recently, he said, "a study of judicial reasoning in same-sex marriage cases concluded that 'most judges appeared to be savvy consumers of social scientific evidence, not easily duped by the misleading operationalization of core concepts, analytic procedures that failed to include proper statistical controls or easily disproved claims of lack of scientific consensus.' Social science can indeed make the difference at the Supreme Court."

Bonilla-Silva went old-school, opting for an open letter. In it, he included “just a few examples” -- contributed by association members -- of the impact sociological research has had on the lives of Americans. They include evidence that separate is not equal (to Rocco's point), early algorithms for detecting credit-card fraud, mapped connections between racism and physiologic stress response, and network analysis to identify and thwart terror structures and capture terrorists.

Some additional evidence, according to ASA: pay grades and reward systems that improve retention among enlisted military personnel, modern public opinion polling, data on gender discrimination in the workplace, family factors that impact outcomes for children, guidance of police in defusing high-risk encounters, and strategies for combatting public health crises such as drug abuse.

The “gobbledygook” comment is not the first time people in government have challenged the legitimacy or the value of the social sciences. But most policy makers tend to reserve their criticisms for the humanities. Then-presidential candidate Marco Rubio’s “We need more welders and less [sic] philosophers” and former President Obama’s “I promise you, folks can make a lot more, potentially, with skilled manufacturing or the trades than they might with an art history degree” come to mind, for example. (Obama subsequently apologized.)

In closing, Bonilla-Silva wrote that ASA was sure social scientists and legal scholars at Roberts’s alma mater “would be disappointed to learn that you attributed your lack of understanding of social science to your Harvard education.” Should Roberts be interested in furthering his education, Bonilla-Silva added, “we would be glad to put together a group of nationally and internationally renowned sociologists to meet with you and your staff.”

And given the “important ways in which sociological data can and has informed thoughtful decision making from the bench, such time would be well spent, he added, directing Roberts to ASA’s executive director, Nancy Kidd.

Kidd said Wednesday that Roberts had yet to take ASA up on the invitation.