You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

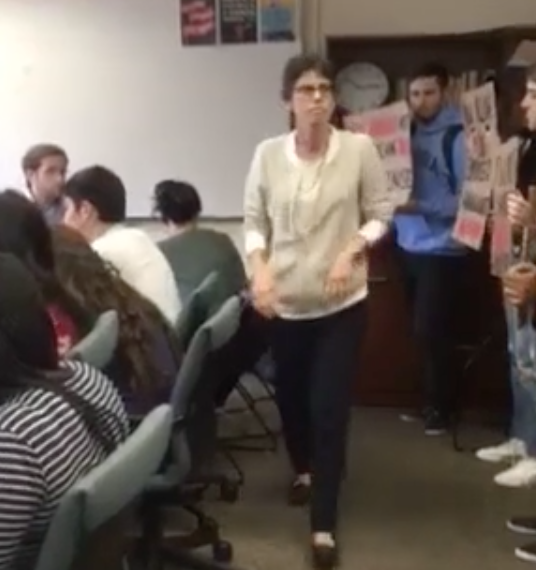

Suzanne Goldberg engages protesters who interrupted her law class at Columbia.

Vimeo

As conflicts over campus speech have accelerated in recent months, most of the incidents have occurred outside the classroom. But a recent incident at Columbia University breached that wall.

Last week, a group of student protesters stormed a small class on sexuality and gender law to protest its instructor, Suzanne Goldberg. The Herbert and Doris Wechsler Clinical Professor of Law at Columbia and an expert on sexuality and gender, Goldberg is also executive vice president of the Office of University Life. The office oversees aspects of the university’s sexual violence response and compliance with Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, the federal law that prohibits gender discrimination and harassment in education.

“We are here today because despite the repeated efforts of student organizers, survivors at Columbia and Barnard [College] are still endangered by administrators like Suzanne Goldberg," says an undergraduate protester, Amelia Roskin-Frazee, in a video of the incident that has since been shared online. She further accused Goldberg of “proudly referring” to her experience as an LGBTQ rights lawyer “while continuing to create a dangerous environment for students, including queer students, on this campus.”

Source: Vimeo

The video shows Goldberg repeatedly asking the students to leave, citing a university policy against disrupting core university functions. After about two minutes, the students depart, protest signs in tow.

Goldberg said through a spokesperson Tuesday that there are “many times in the day when I am glad to meet with students or hear students' views on university life issues, but interrupting a class is never acceptable.”

Disrupting a campus “function” even briefly is against university regulations. But Columbia officials did not respond to a request for comment Tuesday about whether the students involved in the protest would face disciplinary action.

Roskin-Frazee declined to comment other than to say she was one of a group of protesters. She sued Columbia earlier this year over its handling of her complaints about being raped twice in her dorm, in 2015, according to BuzzFeed. Among other concerns, Roskin-Frazee says she was not advised about her full rights under Title IX, that she was told she'd have to pay $500 to move out of her dorm and tell her parents why after the first attack, and that she was initially advised that Columbia could not investigate her report unless she could identify the alleged rapist (she could not).

Sharyn O’Halloran, George Blumenthal Professor of Political Economics and professor of international and public affairs at Columbia, and chair of the University Senate, said the senate does not respond to individual incidents. But she said that the body’s Faculty Affairs, Academic Freedom and Tenure Committee this fall reaffirmed Columbia's commitment to freedom of expression in the classroom. That commitment includes professors' right to choose what they teach, and how -- presumably including the right not to be interrupted.

While a number of invited speakers have been shouted down on campuses recently -- perhaps most notably Charles Murray at Middlebury College, where a faculty organizer was injured in the fray -- classrooms have remained something of a sacred space. There are some exceptions, including a 2013 teach-in by graduate students over a professor’s alleged racial microaggressions at the University of California, Los Angeles. But they remain exceptions.

Will Creeley, senior vice president of legal and public advocacy at the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, said that could change, however, especially if students who interrupt classes in clear violation of campus policies are not held to account.

“Already this academic year, we’ve seen harassing tweets and emails sent to professors whose scholarship is controversial, and it’s all too easy to imagine classroom disruptions by students, alumni and members of the public becoming more common,” he said. “We really have to make sure that professors are not impeded in teaching their classes as they see fit.”

Creeley was reluctant to outline any kind of hierarchy of campus speech disruptions, but he said that classroom interruptions are perhaps more serious than those staged elsewhere, since they “in some ways strike more directly at the core function of the university.” While there’s nothing wrong with teach-ins to which professors have consented in advance, he said, it’s unacceptable to co-opt a class without permission.

Beyond threatening education, Creeley said that classroom interruptions threaten academic freedom, in that it’s a form of “vigilante decision making about who gets to learn and who gets to teach.”