You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

Most Ph.D.s in the natural sciences and engineering leave academe because of the difficult job market, not because they want to, right? Wrong, according to a new study in PLOS ONE.

Authors Michael Roach, the J. Thomas and Nancy W. Clark Assistant Professor of Entrepreneurship at Cornell University, and Henry Sauermann, an associate professor of strategic management at Georgia Tech, found that labor market conditions do prevent some doctoral graduates interested in an academic career from pursuing one -- but a large share lose interest for other reasons.

That matters, the authors say, because “efforts to understand students’ career paths should consider the diversity in career goals" and the broad range of factors than shape them. In particular, “comparisons of the number of graduates with the number of available faculty positions likely overstate the number of Ph.D.s who aspire to a faculty career, thereby exaggerating imbalances in academic labor markets.”

It's good news, according to the study, since the significant share of students who remain interested in academe “alleviates concerns about a potential ‘drying up’” of the faculty pipeline, and means “better alignment between students’ career preferences and the careers they ultimately enter.”

But the findings also indicate that more information, training and flexibility are needed within Ph.D. programs (and maybe even before students enroll in them), according to the study. That way, students can best prepare for the jobs they'll choose.

Roach said Thursday that nonacademic careers "have long been the more common pathway and not the alternative." And most faculty members "have spent their entire careers in academia and are not familiar enough with other career pathways to help guide their students.” Moreover, there isn’t “enough appreciation for the important ways that science and engineering Ph.D.s contribute to society outside of academia, through innovation and economic growth.”

Economists and policy makers have long recognized the "essential role of universities in training industrial scientists," he said, "and applying scientific knowledge and research skills to the development of new medical devices or autonomous vehicles or alternative energy should not be seen as a failure."

The study, “The Declining Interest in an Academic Career,” is based on a longitudinal survey of a cohort of graduate students from 39 U.S. research universities over the course of their training. The central idea was to document changes in those students' career preferences and what might be fueling them.

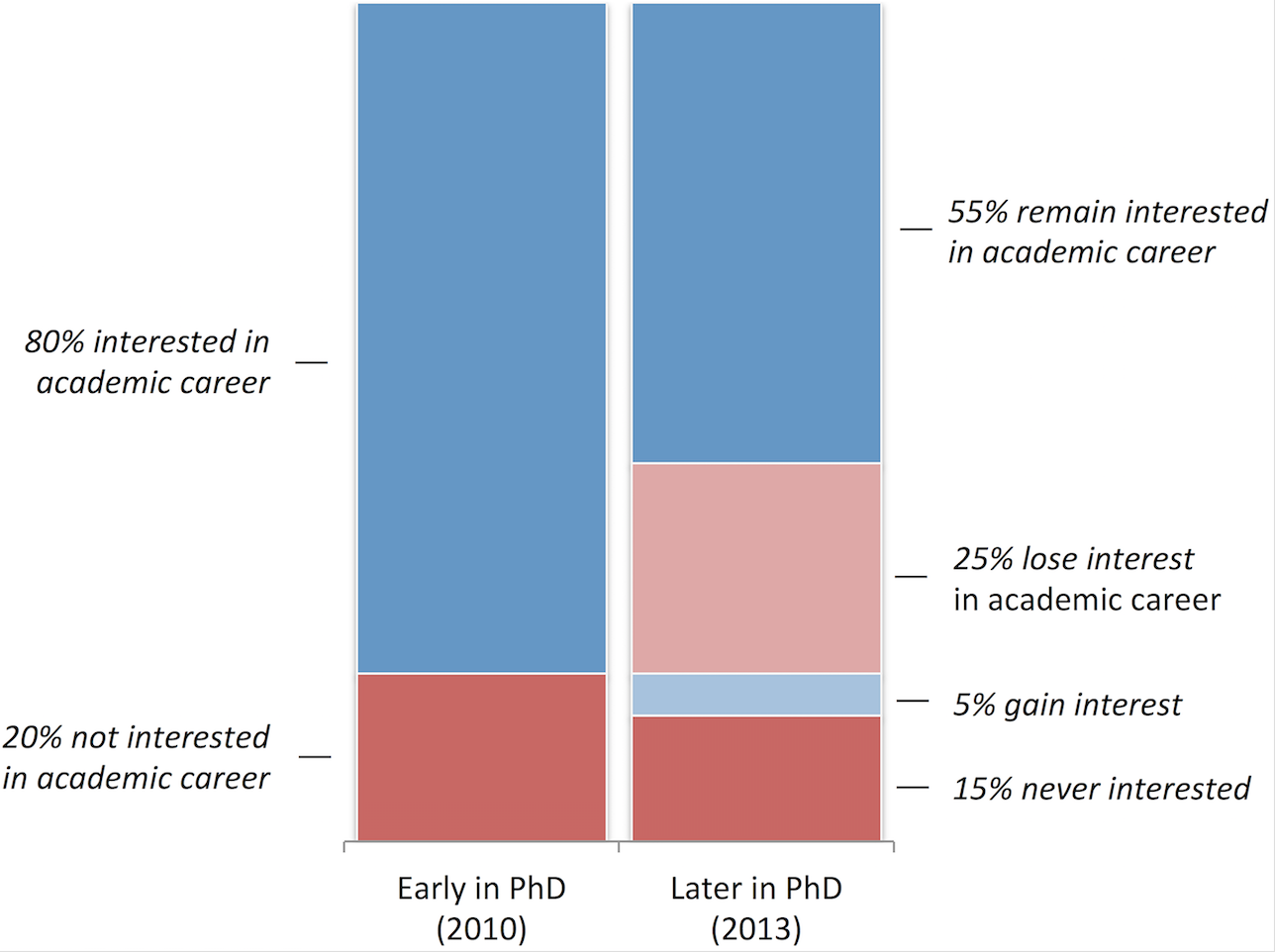

The first major finding is that although the vast majority of students start their Ph.D. training interested in an academic career, that share falls to 55 percent of students over time -- and 25 percent of students lose all interest in academe.

Fifteen percent, meanwhile, were never interested in an academic career. Just 5 percent became more interested in a faculty career during their training.

Source: PLOS ONE

Source: PLOS ONE

Roach and Sauermann say that the declining interest isn’t, therefore, a general phenomenon but rather “reflects a divergence between those students who remain highly interested in an academic career and other students who are no longer interested in one.”

And does the job market drive the drop in interest? No. Rather, it’s misalignment between students’ evolving preferences for specific job attributes, according to the paper, and students’ changing perceptions of their own research abilities. Perhaps surprisingly, the pressure to produce publications -- and the challenges for those who can't -- don’t seem to play a role.

Digging Deeper

Roach and Sauermann followed 854 students over their training in the life sciences (36 percent of the sample), chemistry (12 percent), physics (18 percent), engineering (24 percent) and computer science (10 percent). The 39 universities in the sample were considered tier one and accounted for 40 percent of all graduating Ph.D.s in the natural sciences and engineering. First- and second-year Ph.D. students were invited via email to participate in a survey about their Ph.D. program experiences and career goals, with the first responses reported in 2010 at a response rate of 30 percent. The researchers followed up with respondents three years later, in 2013, and got a response rate of about 40 percent.

To measure career interests, respondents were asked both times, “Putting job availability aside, how attractive or unattractive do you personally find each of the following careers?” The survey asked about a range of research and nonresearch careers inside and outside academe, but the new study focuses on students’ interest in university faculty jobs with a focus on research.

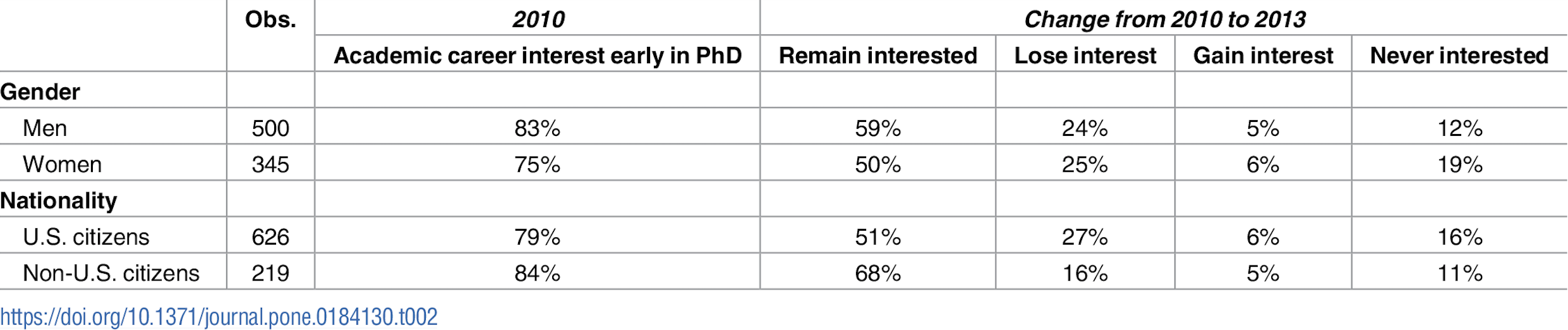

By 2013, nearly one-third of doctoral students surveyed who started their programs as faculty hopefuls lost that spark, and the job also became increasingly less attractive to them on a five-point scale. Men were more likely to start out enthusiastic about an academic career than were women (83 percent vs. 75 percent), and this difference persisted over time, with 59 percent of men remaining interested in an academic career compared to 50 percent of women after three years. Similar shares of men and women reported a decline in their interest in an academic career over time.

In another significant demographic finding, some 27 percent of U.S. citizens lost interest in an academic career compared to only 16 percent of foreign Ph.D. students. Some 51 percent of U.S. citizens remained interested in an academic career three years on, compared to 68 percent of foreign students.

Both the 2010 and 2013 surveys asked students, “What do you think is the probability that a Ph.D. in your field can find the following positions after graduation (and any potential postdocs),” with positions including “university faculty with an emphasis on research or development” and “established firm job with an emphasis on research or development.”

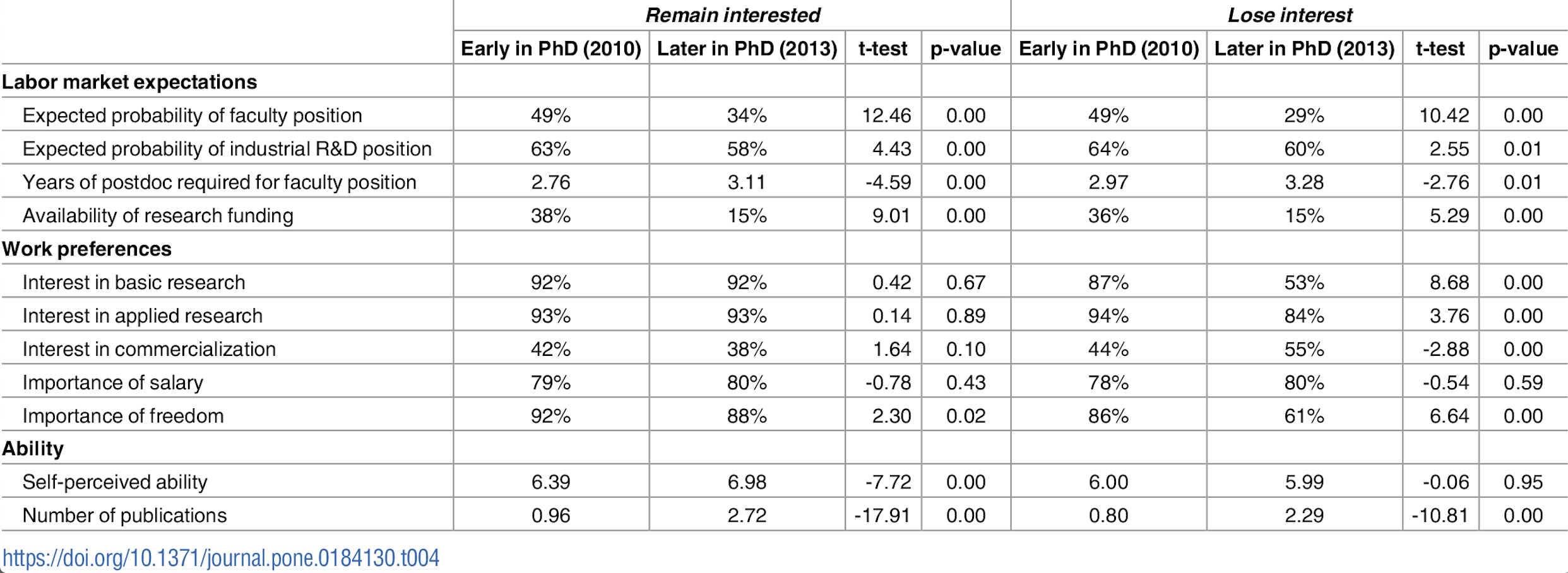

Early in their programs, students expected that about half of graduates in their fields would obtain a faculty position at some point in their careers. Over time that expectation decreased significantly for all students, but irrespective of their interest in an academic career. And while students in the 2013 survey expected that one might spend more time as a postdoctoral fellow than they had in 2010, those responses were also not significantly linked to career aspirations or preferences. So, too, with students’ responses to the question “To what extent do you think research funding is available to faculty members at a research university?”

Instead, non-job-market factors correlated with students’ interest in tenure-track jobs.

Both waves of the survey asked students, “When thinking about the future, how interesting would you find the following kinds of work?” on a five-point scale, for example. Work activities included basic research (“research that contributes fundamental insights or theories”), applied research (“research that creates knowledge to solve practical problems”) and commercialization (“commercializing research results into products or services”). To measure preferences for job attributes, students were asked “When thinking about an ideal job, how important is each of the following factors to you?” Listed factors included “financial income (e.g., salary, bonus, etc.)” and “freedom to choose research projects.”

Early in the Ph.D. program, the vast majority of students have a strong preference for basic and applied research and choosing research projects. Students who remained interested in an academic career later on changed little over time with respect to these preferences. But among students who lost interest, the share with strong preferences for basic research, applied research and freedom decreased significantly, while the share with a strong preference for commercialization increased. Income was not a significant factor.

The authors note that they can’t rule out reverse causality, in that changes in career interests could lead to changes in preferences for work activities and job attributes. But they say their observations are consistent with the idea that preferences in job attributes “shape students’ career interests and suggest that the decreased interest in a faculty career partly reflects changes in students’ preferences.”

As for ability, the surveys asked students to rate their research ability relative to their peers in their area of specialization on a sliding scale. They also asked respondents how many published or accepted articles in peer-reviewed journals listed them as authors (that measure increased from a mean of 0.87 in 2010 to 2.5 in 2013). Students who remained interested in a faculty career started with higher levels of self-reported ability and publications than those who lost interest. Subjective ability increased significantly among those who remained interested in academe but remained unchanged among those who lost interest. Publication counts increased for both groups, but not significantly more for the sustained interest group.

In sum, 40 percent of advanced students aren’t interested in pursuing an academic career, according to the study. Many of those students reported a lack of information about nonacademic career options, suggesting that more information about career diversity is needed earlier in Ph.D. programs. Experiential approaches, such as internships, may be more effective than just workshops and information sessions, the authors say. They also praise programs such as the National Institutes’ of Health’s BEST Program, which promotes programs that broaden Ph.D. training. And advisers still tend to strongly encourage the traditional academic career path.

The authors also note their findings suggest that students would benefit from more information about diverse careers in the sciences before starting their Ph.D. programs, to avoid a mismatch between what they want to do and what kinds of training they need.

“This may allow individuals to take advantage of a growing range of alternative educational options, such as professional science master’s programs, and ultimately result in faster career progress and more satisfying long-term career outcomes.”

Over all, Roach said, the study clashes with the “common assumption” that most Ph.D. students want a faculty career. When students start working toward their doctorates, he said, “many see academia as the typical career path, but as they learn more about what the faculty career is really like and learn more about their own interests, they realize that academia is not for them.”

And among the Ph.D. students in the study who remain attracted to an academic career, he said, more than half also express an interest in industry careers. “So the notion that academia is the only preferred career path and that careers in entrepreneurship and industrial [research and development] are undesirable is a false dichotomy.”

Nathan L. Vanderford, a professor of toxicology and cancer biology at the University of Kentucky, who has studied the gap between Ph.D. training and job outcomes, said that the study captured what he and colleagues observe every day, anecdotally: that the job market doesn’t inform students’ career decisions as much as a growing understanding of what an academic career entails.

Increasingly, he said, given the highly competitive funding environment, being a professor means chasing grants and otherwise dealing with the academic bureaucracy.

“They realize that being an academic is not just about being able to do the research that you love to do every day,” he said of trainees.

Vanderford wholeheartedly supported the paper’s multiple calls for more information for potential Ph.D. students and training for Ph.D. candidates about the job market, both inside and outside academe. He said he’s been teaching a class on exactly that topic for the past four years, so that trainees “can make more informed decisions as they’re making progress preparing for their careers.”