You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

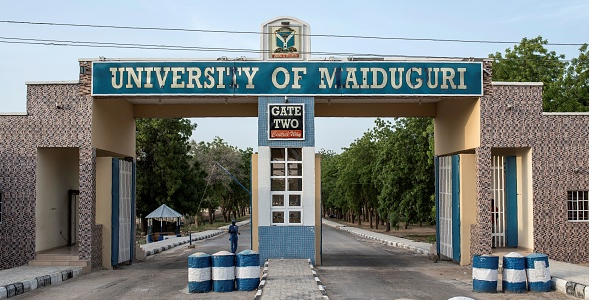

A Nigerian university that has been attacked by Boko Haram

Getty Images

The new edition of Scholars at Risk’s annual “Free to Think” report analyzes more than 250 reported attacks on higher education institutions, their students or their employees in 35 countries in the past year. The incidents examined range from killings or disappearances of higher education workers to what Scholars at Risk judges as cases of wrongful imprisonment, prosecution or termination, or undue travel restrictions.

The report, which covers a period spanning Sept. 1, 2016, to Aug. 31 of this year, describes mass attacks on campuses in Nigeria, Pakistan and Syria. A rocket attack on Syria’s University of Aleppo last October reportedly killed between two and five students, while an Oct. 24, 2016, attack by armed militants on Pakistan’s Balochistan Police College reportedly killed at least 61 people, primarily students. Nigeria’s University of Maiduguri suffered a series of six bombing attacks, killing at least 14 and injuring 33. The attacks have been widely attributed to the militant group Boko Haram, which claimed responsibility for the Jan. 16 attack on the university.

Beyond these mass attacks, the report says that targeted killings of individual students or scholars were reported in Niger, Pakistan and Sierra Leone.

The report from Scholars at Risk, an organization that monitors academic freedom violations worldwide and provides international fellowships for scholars under threat in their home countries, also documents an increase in the number of reported incidents involving violence against organized student protesters.

“In Venezuela, South Africa, Niger, Cameroon, Turkey and India, state authorities responded to nonviolent student protests with force, including with rubber bullets, tear gas and stun grenades,” the report states. “In some cases, however, students engaged in violent or coercive conduct, including incidents in South Africa, where campus facilities were damaged, and in the United States, where physical force was used to intimidate and disrupt disfavored speakers on campus.”

In relation to the U.S., the report spotlights violence that broke out last winter and spring during protests surrounding planned talks by the right-wing provocateur and former Breitbart editor Milo Yiannopoulos, at the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Washington -- where a man was shot in the abdomen and seriously wounded -- and a March 2 protest against a speech at Middlebury College by the controversial political scientist Charles Murray that resulted in injuries to a professor who was moderating the event.

"We did, obviously, this last year see at least a more visible spate of incidents that resulted in violence either on campus or against members of the campus community," said Robert Quinn, the executive director of Scholars at Risk. He said one of the things the organization looks at in compiling the report is not just the location of an incident -- does it occur on a university campus -- but "also dimensions of the intent behind the actions and the effect it has. Are they intended to try to shrink or control the space or intimidate, and do they have the effect? I think in the U.S. in particular my concern is what impact are these incidents having on the space itself and on the understanding of that space?"

Outside the U.S., the report devotes special attention to Venezuela, where economic, political and social conditions have been deteriorating and where student-led antigovernment protests have been met with violent responses from military or police forces. Students have been injured and, in one case, when state security forces confronted protesters on the campus of Orient University in May, a 22-year-old nursing student, Augusto Sergio Pugas, reportedly died of a bullet wound to the head.

SAR also reports that at least 21 students have been killed in off-campus protests in Venezuela and that there have been at least 65 wrongful arrests and detentions of students during the past year. Mayda Hočevar, a professor of law at the University of Los Andes, said students have been accused of crimes in military courts and have been tortured during detention.

A United Nations report this summer corroborates the use of military courts and torture of some detainees and found that the use of force against protesters (all protesters, not just students) had escalated from April to July of this year: "In the first half of April, the majority of injuries were from inhaling tear gas; by July, medical personnel were treating gunshot injuries," a U.N. investigating body found.

"In the U.S. in particular my concern is what impact are these incidents having on the space itself and on the understanding of that space?"

"Governmental authorities keep saying that university students who participate in protests are terrorist[s] and that the universities are den[s] of terrorists," said Hočevar, who monitors events in Venezuela for Scholars at Risk.

The report from Scholars at Risk also includes a section focusing on threats to institutional freedom in Central and Eastern Europe. These threats include the passage of a new law in Hungary that imperils the continued operation of Central European University in Budapest and the revocation of the teaching license of the European University at St. Petersburg. (The university has applied for a new license.) CEU, an American-accredited institution, is widely believed to have been targeted for its connections to the liberal financier George Soros, while EUSP, another Western-style institution, came under government scrutiny after a Russian politician reportedly criticized its research and teaching in gender studies as “fake studies” that “may well be illegal.”

In addition, the report devotes considerable space to continued threats to academic freedom in Turkey, where firings and arrests of scholars on suspicion of links to a failed coup attempt in July 2016 have resulted in what Scholars at Risk calls an “unprecedented threat to a national higher education system.”

Between January 2016 and Aug. 31 of this year, Scholars at Risk estimates, 7,023 Turkish higher education employees were dismissed from their positions and barred from public employment and traveling abroad; 1,404 scholars, staff and students were detained, arrested or named in arrest warrants; 407 higher education personnel and students were criminally charged; and 294 graduate students were expelled from their Turkish institutions while studying abroad. In addition, more than 60,000 students have been affected by state-ordered closures of universities.

Quinn, the executive director of SAR, described what he saw as “a very worrying pattern of serious pressures in states that previously we would have thought of as more respectful of the space of the university and academic freedom. That’s clearly Turkey, which has made a significant turn in a negative direction, but then [there’s] also the Eastern European stuff and even some of the attempts on the U.S. side on the restrictions on travel.” (President Trump issued a new set of restrictions on travel Sunday to replace an expiring 90-day ban on travel to the U.S. for nationals of six Muslim-majority countries.)

“What you’re seeing I think is an erosion of respect for the idea that society tolerates questions,” Quinn said. “And when the state starts to punish people simply for asking questions, that’s not just a threat to academic freedom, that’s a threat to democracy. Obviously, if the previously generally rights-respecting states are having their own democracy erode, they’re less viable partners in trying to help states that have bigger security problems.”

In addition to cases involving violence and prosecutions or imprisonments, the report also examines the issue of travel restrictions barring the entry or exit or ordering the expulsion of specific scholars or students in China, Egypt, Israel, Malaysia, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda and Vietnam. The largest-scale example of this comes from Turkey, where the report describes the move to invalidate the passports of scholars and others as “part of a larger set of measures, including mass terminations and bans on future employment … that aim to identify and penalize public employees accused (often with little evidence) of supporting Fethullah Gülen, the cleric Turkish authorities have claimed was behind the July 2016 coup attempt. The invalidation of passports is particularly harmful, as it not only prevents a disfavored class of scholars from engaging in academic expression abroad but also is effectively the final step in a career-destroying effort: scholars who are already prevented from pursuing their careers at home are also barred from seeking employment anywhere else in the world. Under the decrees to date, 5,623 scholars, 1,299 administrative staff and their spouses are barred from leaving the country.”