You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images

What hiring committees want is a black box to many, if not most, Ph.D.s on the tenure-track job market. A new study out Tuesday in Nature Biotechnology seeks to keep biomedical sciences professor hopefuls, in particular, from flying blind. The study, based on a survey of what mattered to one search committee in particular, doesn't claim to be entirely representative of all searches. Yet the authors say the committee's approaches were typical for the field.

“I’m very interested in this gulf between the number of Ph.D.s being produced and the limited supply of tenure-track faculty positions available,” said co-author Nathan L. Vanderford, a professor of toxicology and cancer biology at the University of Kentucky. “That and the lack of really relevant training provided to Ph.D.s, relative to the jobs they’re actually getting.”

The news isn’t great, but findings at least confirmed Vanderford’s (and common) suspicions that hiring committees value not only scientific expertise, but also social “rank” -- think journal impact factor and institutional prestige. In fact, in the recruiting effort studied, publication record was a primary factor in an applicant having been considered. For assistant professor candidates, their mentors’ reputations mattered greatly.

Among other measures to counter that dynamic, Vanderford and his co-author, Charles B. Wright, a science policy analyst at the National Eye Institute, recommend blind initial reviews of faculty candidates by hiring committees. That would mean stripping not only their names from applications but also the names of their Ph.D.-granting institutions and mentors, to focus almost entirely on the candidates’ research potential.

“What Faculty Hiring Committees Want” starts with some grim statistics. Among them: roughly two-thirds of Ph.D.-holding trainees are in the life sciences, but only 14 percent of them eventually secure tenure-track jobs. What does it take to get one of those jobs? To find out, the authors surveyed a seven-member faculty hiring committee tasked in 2015 with recruiting new assistant, associate or full professor hires to Vanderford’s department and the Markey Cancer Center at Kentucky.

Wright and Vanderford, who was part of the committee, explain that applications were initially screened for current grant funding, high-impact journal publications and research-area fit with the program. The most promising candidates were invited for in-person interviews with current faculty, a public presentation and an additional “chalk talk.” The committee met afterward to determine whether it would continue to recruit these candidates; two assistant professors eventually were hired.

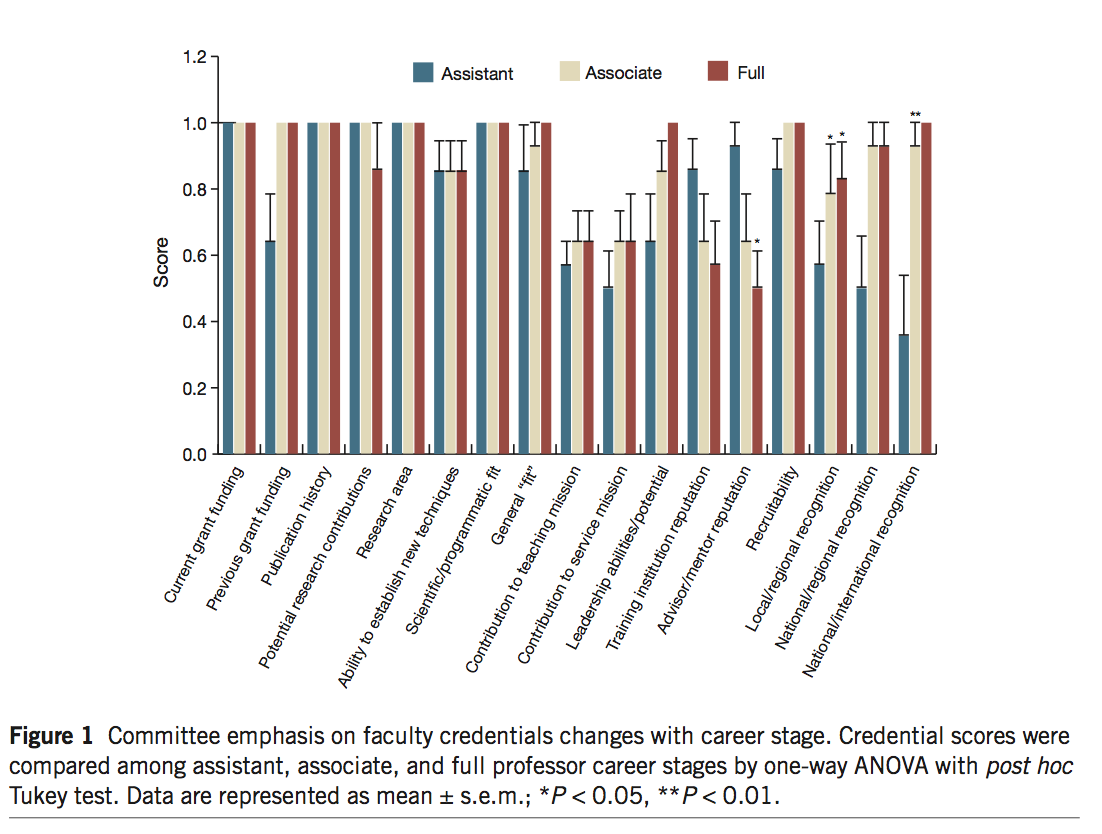

The survey asked individual search members if they strongly agreed, agreed, disagreed, strongly disagreed or were neutral as to whether each of 17 different credentials mattered in the search. Candidates’ career stages were taken into account.

Credentials fell within four categories: core competencies that mattered to a search no matter the candidate’s career stage; “initial necessities” that mattered in securing an early-career hire; “necessities for advancement,” or credentials that gain importance over one’s career; and “unnecessary credentials,” which were scored neutrally across career stages.

Journal impact factor and social hierarchy played outsize roles in career advancement, according to the study. Institution reputation trended toward significance, and adviser or mentor reputation was considered important for assistant professor hires. The study asserts that all these rely on perceived social status, which does not necessarily equal scientific quality or merit.

Source: Nathan Vanderford

Vanderford and Wright recommend, first and foremost, eliminating journal impact factor as a consideration in hiring. “An applicant’s publication record should instead be judged on the strength of data and experimental design in the context of the applicant’s field of study,” they say, noting approvingly that the Kentucky committee asked candidates to include a research program statement about how their work would enhance the department and center.

As for blind review, the authors propose that hiring committees coordinate with human resources departments to assign unique identifiers to each applicant so cover letters are stripped of personal information. Again, that includes name, training institution and mentor, as “all introduce bias in hiring considerations.”

“We believe applicants could highlight their research productivity, vision and value without disclosing personal information,” the study says. “Once the committee identifies promising candidates, the human resources department could then provide other application materials (for example, curriculum vitae) to the committee.”

Vanderford said he acknowledged that larger structural problems underlie the relative lack of tenure-track jobs relative to Ph.D. trainees, including decreased tenure-track faculty lines, the postdoctoral system some long-term trainees have dubbed the “permadoc” system, and decreased federal research funding.

That last factor in particular can make committees hawks for candidates, even new assistant professors, who can bring external funding with them -- something virtually unheard-of in the not-so-distant past, Vanderford said. And while the study doesn’t address those underlying issues, it doesn’t condone them, either. If anything, Vanderford said, his study might help those waiting year after year for the elusive faculty job to cut their losses and pursue other, more fulfilling career paths.

Gary McDowell, a biophysical scientist, decided to leave academe behind and now advocates for junior scientists as executive director of the nonprofit Future of Research. Via email, he said he wasn’t too surprised by the study in terms of what’s valued in hiring, but agreed “very much with the idea of greater transparency about what is being looked for.”

“It seems that every time there is a discussion about what one should or shouldn't do in applying for faculty jobs, there are things that everyone has completely opposite advice/experience on, and sometimes contradictory advice is received,” he said, “which makes the process very confusing.”

McDowell also said he agreed with the idea of a “blinding” search committee members to certain information upon initial review, since a relatively small number of institutions are so overrepresented among those who eventually win tenure-track jobs. But he noted that blind review might be difficult in smaller fields, where applicants and mentors could be recognizable even without their names or institutions.

Karen Kelsky, a former tenured professor who runs an academic job consulting service and blog called The Professor Is In, said she supported the idea of a blind review process, and noted that it would also correct some gender and race bias. At the same time, she said, “any job seeker who doesn't understand that the job search is a status exercise has been badly misled.” One of her client interventions is to help people understand that before they even apply to a graduate program, she said.