You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images

Efforts to diversify the faculty may not be focusing enough on key areas, namely math-based fields -- especially when it comes to black faculty members. And such efforts haven’t led to any premium in pay for those hired to contribute to campus diversity. That’s all according to a new study of faculty representation and wage gaps by race and gender in six major fields at 40 selective public universities.

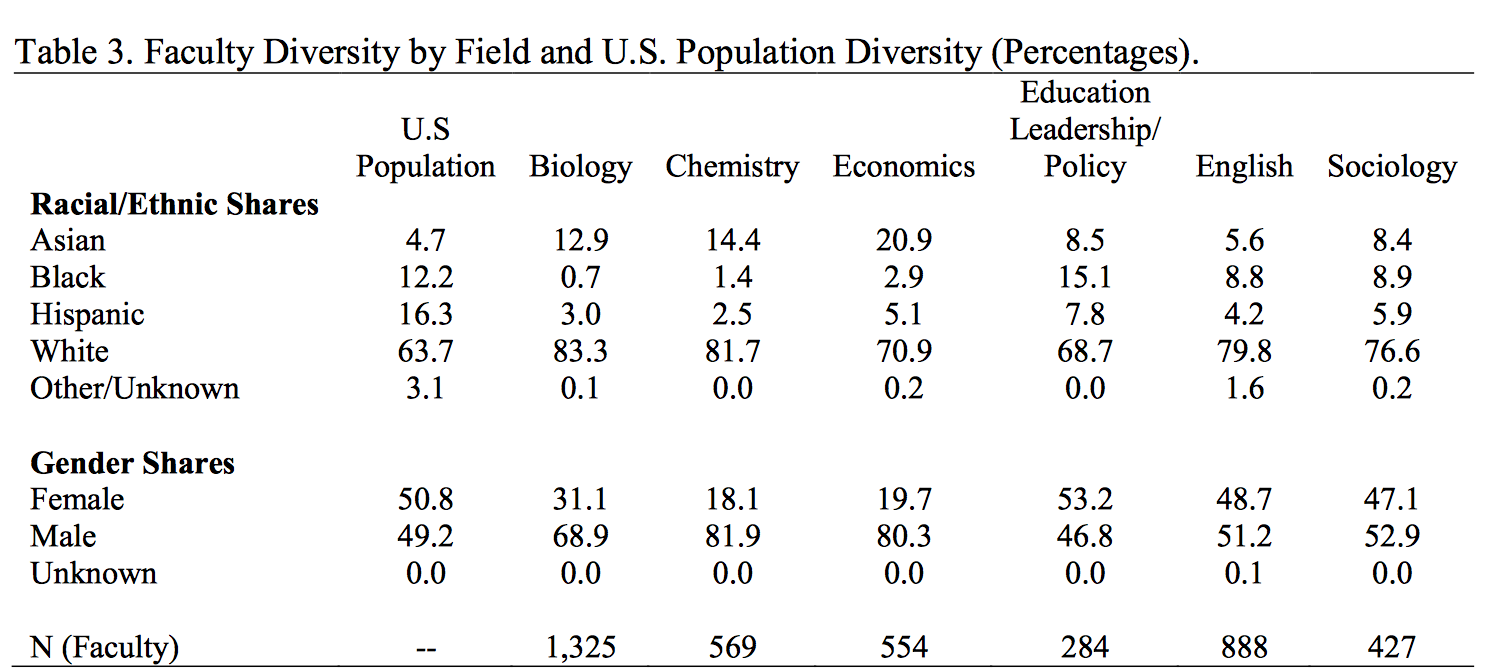

Consistent with existing research, the study says, black, Hispanic and female professors are underrepresented, while white and Asian professors are overrepresented across disciplines. But nearly all of that can be attributed to underrepresentation of black and Hispanic men and women and women of all backgrounds in the natural sciences, technology, engineering and math, it asserts.

A comparison of senior and junior faculty members suggests increasing diversity over time -- especially in STEM -- except for a key group: black faculty members.

The study attributes observed differences in faculty representation by race and gender to related differences in the number of Ph.D.s in various academic fields, and their backgrounds and experience. Again, though, the exception is black faculty members, who are overrepresented in non-STEM fields relative to Ph.D. production, and underrepresented among STEM faculty relative to Ph.D.s granted.

Those same factors explain some of the disparities by gender, but not all, according to the study.

“If a rationale for policies to improve faculty diversity is to provide role models for underrepresented students, and if it is presumed that students will gravitate toward such role models, the current diversity imbalance in higher education implies that students from underrepresented groups may be nudged toward lower-paying, non-STEM fields,” the study says. “This would serve to perpetuate an already-existing imbalance in the work force, both in academia and the broader labor market.”

A simple takeaway is that “STEM and non-STEM fields exhibit very different diversity conditions, which merits consideration in the design of policies” to increase faculty diversity, the study notes.

“Representation and Salary Gaps by Race-Ethnicity and Gender at Selective Public Universities,” published this month in Educational Researcher, was written by Diyi Li, a Ph.D. candidate in economics at the University of Missouri at Columbia, and Cory Koedel, an associate professor of economics at Mizzou. They note that their campus, among others, has been a seat of student unrest concerning faculty diversity, or lack thereof: at Mizzou, for example, the Legion of Black Collegians has demanded an increase in the percentage of black faculty and staff members campuswide to 10 percent by this academic year.

Although it is “straightforward to obtain aggregate data on faculty representation at universities,” the authors say, “contemporary policy discussions would benefit from more detailed information.” For example, they say, “it would be useful to know how faculty diversity compares across fields, and whether universities are behaving in a way consistent with placing independent value on a faculty member’s contribution to work-force diversity.”

To inform such questions and conversations, Li and Koedel looked at racial and gender diversity and wage gaps on 40 campuses in six departments they considered “inclusive” of STEM and non-STEM fields: biology, chemistry, and economics; and educational leadership and policy, English, and sociology, respectively. Data were hand collected from public institutions holding top slots in the U.S. News & World Report rankings and concerned mostly tenure-track and tenured professors in the 2015-16 academic year.

Source: Cody Koedel

Source: Cody Koedel

In addition to finding that that underrepresentation of black, Hispanic and female faculty members is driven by the STEM fields, the paper also says that patterns of racial and gender representation by field generally align with patterns in Ph.D. production. (Doctoral data were taken from the National Science Foundation's Survey of Earned Doctorates.)

Examining faculty representation by rank, the authors found that assistant professors are less likely to be white and more likely to be Asian and Hispanic, and less likely to be male, than associate and full professors. That’s true of all fields, especially those in STEM.

The glaring exception, of course, is that black faculty members are just as underrepresented among junior faculty members as they are among senior faculty in STEM.

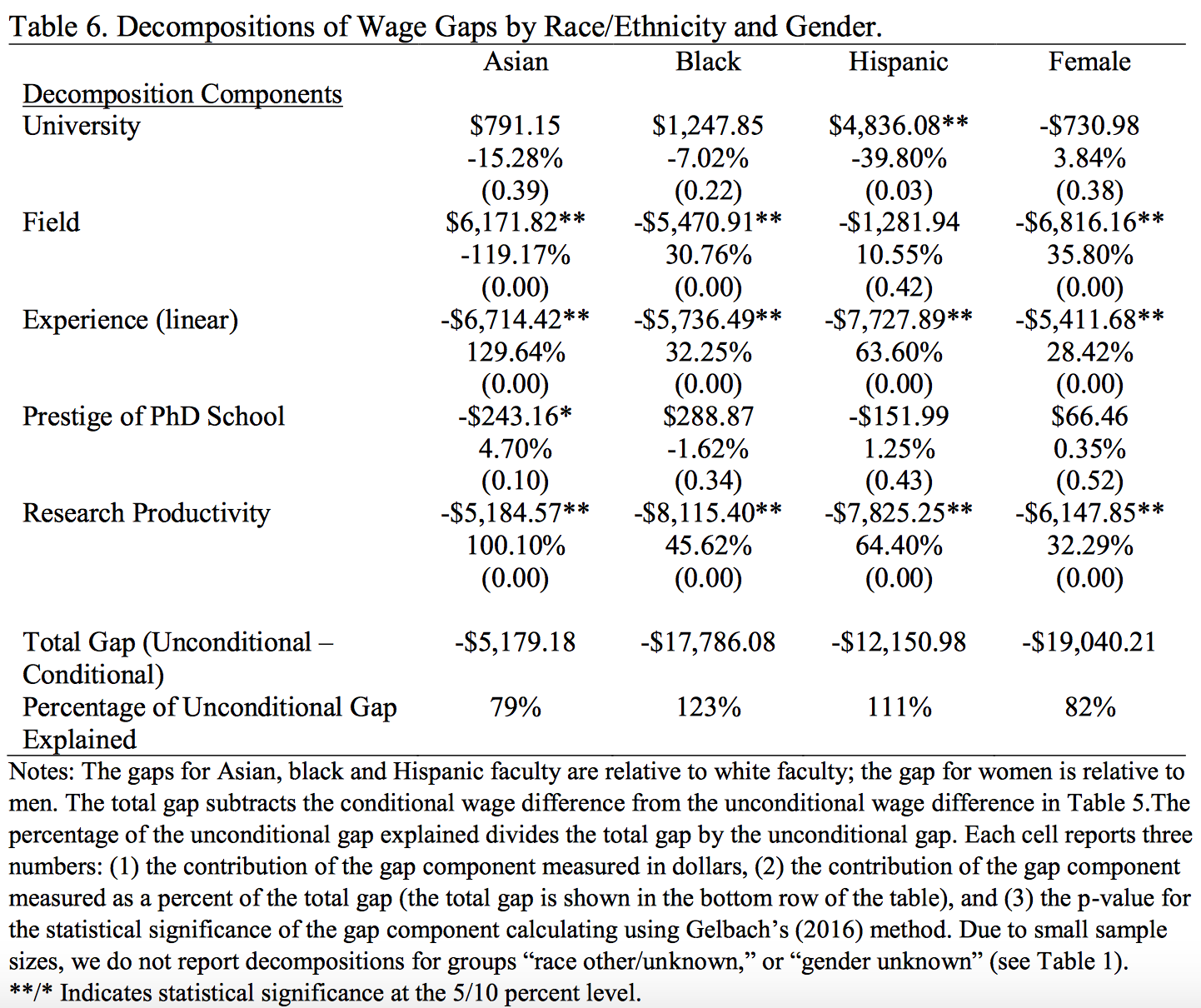

Regarding wage gaps, the study says that black and Hispanic male faculty members earn, on average, $10,000 to 15,000 less annually (unadjusted for any factors) than their white counterparts. That’s about 8 to 12 percent over the average wage studied, some $120,195. Adjusted for various factors, however -- namely academic field, experience and research productivity -- the racial wage gap generally disappears.

The unconditional or unadjusted gender gap is even larger, at about $23,000. Controlled for various factors, the wage gap between men and women shrinks to about $4,000 -- but that’s still statistically significant, according to the researchers.

Koedel said Monday that a major takeaway is that underrepresented minority and female faculty members have a much higher representation in lower-paying fields, even when non-tenure-track faculty members (who are disproportionately female and underrepresented minorities) are excluded from the sample.

And of the finding that there's no apparent wage premium for faculty members who increase campus diversity, despite many institutions having launched major campaigns around that goal? Older research did not identify a wage premium, but some may have expected that to change in recent decades, Koedel said.

The study notes that one way to increase faculty diversity in STEM without the ability to offer a premium is to recruit from lower-ranked departments. There’s little evidence that that’s happening thus far, though. Koedel said he didn’t know whether his findings would be different at major private institutions, which presumably would have more flexibility in terms of allocating funds for hires that contribute to diversity goals.