You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Many community colleges are moving away from placement exams as a means of determining the skills of incoming students.

Now the California State University System is planning to do the same in an effort to increase graduation rates, despite lingering concerns from some officials and faculty members that removing the tests may hurt students in the long run.

“We’re trying to increase the number of students who can go right into college course work to get college credit instead of track students into remediation for various reasons,” said April Grommo, director of enrollment management services for the system, adding that the system would discontinue the use of early placement tests as soon as 2018 and instead rely on high school grades and course work, SAT or ACT scores as measures to determine college readiness.

The move is part of the system’s long-term goal known as Graduation Initiative 2025, which is a series of steps Cal State is taking to increase the four-year graduation rate from about 20 percent today to 40 percent in the next eight years. The goal also includes increasing the six-year graduation rate from 57 percent in 2015 to 70 percent in 2025.

The Cal State system currently uses its own English and math exams designed by Educational Testing Service to determine placement.

The system already uses the SAT, the ACT and the state assessment given to K-12 students as a method to exempt students from taking placement exams altogether. But under the new policy, in order for students to be considered "conditionally ready" for English, they would have to meet a similar standard on the state's Early Assessment Program exam, which is given to 11th-grade students, score between a 510 and 540 on the SAT's reading and writing section, or score between 19 and 21 on the ACT English section. Students considered to be "conditionally ready" in math would also have to meet a similar standard on the EAP exam, score between 520 and 560 on the SAT math section, or score between 20 and 22 on the ACT math test.

Students could transition from conditionally ready to "ready" in math or English if they completed approved 12th-grade courses or transferred college courses that satisfy the requirement with a grade of C or better.

But if students score below those benchmarks and were considered conditionally ready, the system would introduce the review of high school course work and grades to determine placement, Grommo said, and if based on all factors the student is found not to be college ready, they would be required to attend the system's early-start course in the summer.

Grommo said the system is still gathering feedback from campuses, community college partners and K-12 systems across the state, so the new policy isn't finalized yet.

"We are introducing the evaluation of high school course work and discontinuing the placement test since we already have passing scores for ACT, SAT and EAP in place," she said. "By introducing high school course work as an additional placement method, less students will need remediation and can start in college credit-bearing courses with additional support."

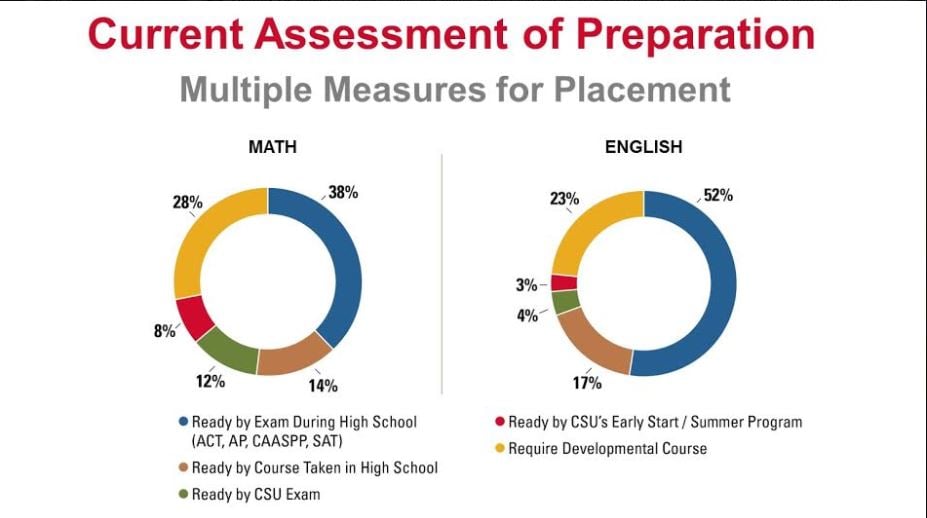

Systemwide 28 percent of students are placed in remedial math and 23 percent in remedial English, Grommo said. The system serves about 480,000 students.

In math, 38 percent of students are considered ready for college-level course work -- 52 percent in English -- by the time they graduate from high school, but after they've taken the state exam, the ACT, SAT or AP exam. When it comes to the current placement exams, 12 percent of students are considered ready in math and 4 percent in English are ready for college-level courses.

Removing placement exams isn’t the only angle in the initiative to increase graduation rates. The chancellor’s office is also directing campuses to create “stretch” courses and supplemental courses. Stretch courses, unlike traditional remediation, would give college credit to students who might not be likely to succeed in college-level courses and provide them with more time with instructors and additional support. Some campuses, like Cal State Long Beach, already offer stretch courses. The system is also expecting campuses to beef up early-start programs to provide additional support to incoming students in the summer.

Researchers have been learning for years now that some students who are placed in remedial courses because of placement tests would actually be better served in college-level courses. Students often don’t receive college credit for remedial or developmental education courses. Those classes may also increase barriers to completion by using up students’ financial aid resources.

“We know success of remedial courses, especially at community colleges, is less than stellar, and students trapped in remedial aren’t able to move forward and earn college credits,” said Michele Siqueiros, president of the Campaign for College Opportunity, a California-based nonprofit that seeks to build support for public higher education. “The movement toward multiple measures is a better one, and having one high-stakes test … is inefficient. Students’ abilities can’t be appropriately measured by one aspect, and testing them on multiple measures should be the approach.”

A 2012 study from the Community College Research Center at Teachers College at Columbia University found that up to a third of students who tested into remedial courses because of college placement tests could have passed college-level classes with a grade of B or better.

However, there has been less focus and research on eliminating placement exams at four-year universities.

"Although there's no reason to assume the results will be different at universities," said Pam Burdman, a higher education policy analyst and fellow at the Opportunity Institute, a nonprofit that promotes social mobility based in Berkeley, Calif., "my hope, since they're going ahead with this, is that CSU will monitor and evaluate the outcome of this policy and how it impacts students. But a lot of research has shown, particularly in math, remedial course taking doesn't benefit students in terms of their future college outcomes."

Burdman said there shouldn't be a concern for students attending a STEM-focused campus like California Polytechnic State University, with majors in highly technical disciplines, since the requirements in math would already be stronger.

But admission standards are so selective on those campuses that students wouldn't be affected by the CSU policy change on placement tests, Matt Lazier, media relations director at Cal Poly, said in an email, adding that none of the university's new students are remedial. The grade point average for the incoming freshman class is 4.04, the ACT average is 31 and SAT average is 2085.

Meanwhile, at Cal State Long Beach, President Jane Conoley said the campus already has stretch courses, but she sees this as an opportunity to redirect remedial resources into learning communities, supplemental education and cohort-based training that research has already proven helps students who are the least prepared for college-level courses.

“Whether grades or a placement exam, nothing is perfect, but we’ve been going down this path for a while to get rid of these dead-end courses students don’t do well in, they have to repeat and don’t get credit for,” Conoley said, adding that 30 percent of Long Beach students require remediation. “There is a concern faculty may have that they may get students not as prepared, but my dream is all the resources invested in remedial would be moved to stretch courses and to support faculty members.”

And although most of the movement on eliminating placement tests has been at the community college level, Conoley said regardless of whether they are in high school, community college or a university, students presented with a challenge will rise to meet it and "lowering expectations slows them down for graduation."

For many faculty members, grading placement exams isn’t a thrilling venture, but there needs to be some type of assessment that communicates students can enter an undergraduate class, especially when the reality is that many students do need some type of remediation, said Steven Filling, a professor of accounting and finance at CSU Stanislaus State and chapter president for the California Faculty Association.

"CSU is mandated to take the top one-third of graduating [high school] students," Filling said. "Our population is pretty broad, but it's still the top third. We're interested in our students being able to successfully process what is going on in the university system, but placement exams are there in the first place because high school grades don't give you all the information you need. There's a lot of variability out there."

The Stanislaus campus already has stretch courses, as well.

“Politically it would be wonderful to say we’re getting rid of any kind of placement exam or developmental remedial education and everyone thinks it’s progress,” Filling said. “But we’re not sure that’s progress, because we haven’t solved the problem of people not being engaged in quantitative reasoning as they approach problems in their lives.”

Ultimately, Filling said, he hopes CSU administration understands the complete implications of what these changes may mean to students and wishes they had talked to more faculty about how these changes may affect students.

The Cal State English Council, for example, issued a statement expressing dismay at the speed with which the shift to end placement exams has happened.

"While many first-year writing programs are in favor of retiring the [early placement test], this is not a universal opinion, which speaks to the need for campus autonomy in determining assessment measures for placement," the statement said.

Some campuses have transitioned to directed self-placement, which has eliminated the need for the placement exam, but the council feels each campus should be able to decide its own assessment measures for placement.

“Yes, I want to see the graduation rate go up, and I’ll do anything within bounds to make that happen, but to me graduation is a metric for something else,” Filling said. “We can’t just focus on how many diplomas we hand out and forget that’s not what we do. We’re trying to educate people.”