You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

California is one of several states where lawmakers are considering changes to student financial aid programs.

State of California

Several states are taking a hard look at high-profile student financial aid programs as they debate their budget priorities, searching for savings and reconsidering how they spend money on scholarship and grant programs.

In several cases, the issue centers on funds that help middle-class families, aid that some see as essential and others criticize as diverting public resources away from poor students who need them most.

Their discussions have not always grabbed the top headlines in a year when New York sucked up attention by creating a new tuition-free public college program -- and at a time when closely watched reports on state higher education finances and state-funded student financial aid have generally shown increases across the country. But budget debates unfolding in California, Louisiana and Oregon provide examples that even with a strengthening national economy, some states must prioritize amid budget crunches or questions about the most effective spending strategies.

Those hard choices often have lawmakers balking at the idea of cutting funding for their better-off constituents. They also have some advocates of higher education access renewing their arguments that money is best spent on students who cannot finish college without it.

The budget decisions being debated lay bare the choices states must continually make on whether to fund students based on their financial need or their academic performance -- and how much money they can provide in a world of finite resources.

“There is just sort of a lot of evolution going on,” said Frank Ballman, director of the Washington office of the National Association of State Student Grant and Aid Programs. NASSGAP has noted states are increasingly aware of the benefits of need-based aid in recent years.

It’s not so simple on the ground, however. In California, for instance, Governor Jerry Brown has proposed phasing out the state’s relatively new Middle Class Scholarship program, which is based on students’ family income levels.

That program, which first went into effect for the 2014-15 academic year, goes to students at the University of California and California State University systems. It was intended for students whose families make too much for them to qualify for other need-based financial aid programs but do not make enough to allow them to easily pay for college in a state with many regions where the cost of living is high.

The program was to be phased in over time, offering various amounts to students based in large part on their family income. Award amounts also varied based on the number of students eligible and amount of funding set aside in the state budget, but the awards could cover up to 40 percent of a student’s tuition and fees after being combined with other publicly funded financial aid awards. Currently, California students from families with annual income of up to $156,000 are eligible. An asset cap has also been added, preventing those with household assets of more than $156,000, not including primary homes and retirement accounts, to be eligible.

Brown, a Democrat, continued to call for phasing out the Middle Class Scholarship when he released a revised budget proposal this month. Doing so would save an estimated $115 million once the phaseout is complete. Some have objected, however. State Senator Janet Nguyen, who authored a bill to preserve the scholarship, issued a statement arguing that the Middle Class Scholarship program is a “financial lifeline” that is often the only state financial assistance available to students.

The program has provided aid to an average of 50,000 students annually over the last three years. Maximum award amounts have been climbing as the program was scaled up. In theory, the maximum possible award for a Cal State student this year was $1,644, and the maximum award for a UC student was $3,690. Average award amounts have been much lower in practice, however. Cal State students averaged an $800 award this year versus $1,107 for UC students, according to data posted in February.

More than 80 percent of the program’s 46,306 recipients go to the lower-cost Cal State institutions, which also tend to attract students from lower-income backgrounds than do UC institutions. In total, the program paid about $31.2 million to Cal State students and $8 million to UC students.

That’s a relatively small amount in comparison to the total financial aid Cal State students receive, said Dean Kulju, director of student financial aid services and programs at the system.

“Those numbers sound big taken for themselves, but keep in mind that overall total financial assistance from all sources for us is $4.1 billion -- with a ‘b,’” he said.

The number of Cal State students receiving money through the Middle Class Scholarship program is also dwarfed by the number receiving money from the state’s Cal Grant program, which covers students from lower-income families. The Cal Grant income limit for a family of four was $90,500 in the most recent year -- which may seem like a solidly middle-class income if not for the fact that it can be extremely expensive to house a family in California. About 121,000 Cal State students received Cal Grants last year.

Kulju hopes to see the Middle Class Scholarship continued, but with some changes. Right now, students are not told until the summer if they are receiving an award. But students make enrollment deposits months before that. If they learned about their awards earlier, students would be able to factor them into their college choices, he said.

Still, it is too soon to judge the program’s overall effectiveness, Kulju said.

“So far, there’s not enough of a track record to see if it’s truly impactful and the most effective way to go about this for families,” Kulju said. “The budget hawks would argue that it’s still a however-many-hundred-million-dollar drain on the state general funds. Those funds could be used elsewhere.”

Recipients of the Middle Class Scholarship have tended to skew toward its upper income limits. The program makes a small amount of awards to low-income families -- 13 percent of its recipients came from families with household incomes of $50,000 or less. But the bulk of its recipients are from families earning more than six figures. Slightly more than half, 51 percent, fell into the household income brackets between $100,000 and $156,000 this year. Only 36 percent earned between $50,000 and $100,000.

Many would rather see the state use the money dedicated to the Middle Class Scholarship to shore up California’s other student aid programs. The Middle Class Scholarship was not designed to benefit the students who need the most help, said Debbie Cochrane, vice president of the Institute for College Access and Success, a nonprofit that wants to make higher education available for students from more backgrounds.

When Brown proposed eliminating the Middle Class Scholarship, the idea was that doing so would protect the Cal Grant program, Cochrane said.

“If you’re going to choose between those two things, that’s the right priority,” Cochrane said of choosing the Cal Grant program.

Brown is also proposing to stop a scheduled reduction in Cal Grant money going to private colleges. But it’s too early to tell whether that is a net positive for students, Cochrane said.

Preparing for the Next Downturn

The discussions in California fit into a national landscape in which most states are recovering or recovered from the Great Recession, she said. They are also, however, warily eyeing the next possible economic downturn. In some cases, that has policy makers deciding whether to restrict programs based on students’ family income or academic scores.

“They’re trying to make smart decisions about where to invest,” Cochrane said. “And they are making choices of need versus merit.”

The dynamic has been on display in another state widely considered to have struggled in the years since the recession, Louisiana. Lawmakers there are debating changes to the Taylor Opportunity Program for Students.

The program, known as TOPS, is a set of merit-based scholarships paying for tuition for students who finish a core high school curriculum, earn a minimum grade point average and score at or above a minimum level on the ACT.

Louisiana spent about $2.6 billion on TOPS between 1999 and 2016. But expenditures have risen drastically during that time as institutions increased tuition and the number of award recipients rose. Total TOPS expenditures jumped 391 percent from 1999 to 2016.

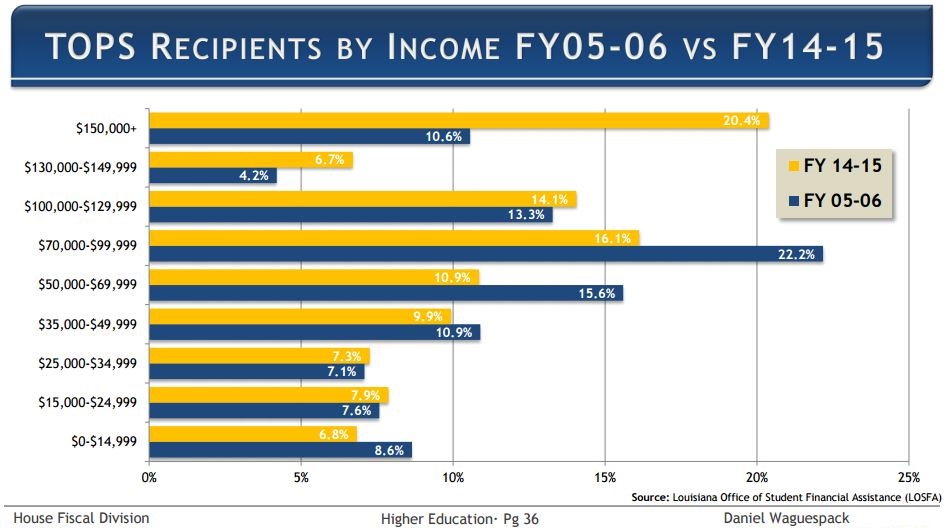

The program has also been criticized as developing into a giveaway disproportionately benefiting the state’s wealthy. In 2005-06 just 10.6 percent of TOPS recipients earned $150,000 or more, according to the Louisiana Office of Student Financial Assistance. By 2014-15, 20.4 percent did so. The portion of recipients from families in income brackets earning less than $100,000 generally fell or held essentially steady over that time.

At the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, that meant a student who normally would have received a $2,700 in TOPS funding this spring only received $1,130, said DeWayne Bowie, the university’s vice president of enrollment management. Some students had to borrow more to make up the difference, he said. Some had to decide to attend another institution where they could afford tuition.

“We had a few students who actually had to stay closer to home to be able to afford to attend school in the semester,” he said. “As far as a large number of students not attending, we didn’t see that. We just saw students -- and still see some students -- that are struggling to make payments.”

Lawmakers have debated a number of ways to rein in the program’s cost and change the way its awards are distributed when there isn’t enough money available. A 2016 law decoupled TOPS award levels from tuition, setting the 2016-17 award level as a base. That puts any future award increases in the hands of the Legislature.

This month a bill requiring higher academic standards for high school graduates starting in 2021 moved through committee. It would require students to earn a 2.75 grade point average on core high school curriculum, up from a current requirement of 2.5.

Another bill would have protected the awards of top-scoring students and those from families with incomes of about $60,000 or less in the event of a TOPS funding shortfall. It did not survive committee. Earlier this year a State Senate panel killed a bill that would have required students to pay back some of their TOPS awards if they moved out of state shortly after graduating.

In a state with a budget that is heavily dependent on the struggling energy sector, funding the TOPS program to increase every year with tuition was not sustainable over the long term, said Joseph C. Rallo, Louisiana commissioner of higher education. Public funding for educational institutions has been slashed drastically over time, forcing them to raise tuition. TOPS had been matching those tuition increases dollar for dollar.

The question now is the best way to allocate money in order to support students across the state. Are the current TOPS academic standards too low, turning it into a de facto giveaway for all students, regardless of whether they study hard? Does the program spend too much on wealthy students who could afford tuition on their own?

Or has the program simply become too broad?

“If you want it to be merit-based, then perhaps you want to look at enhancing the requirements,” Rallo said. “If you want to make it need-based, then step up.”

Rallo pointed out that Louisiana has a need-based grant, the Go Grant, that has not received additional funding in recent years. TOPS distributed $254.9 million in 2015-16. Go Grants distributed just $26.5 million. More than 50,000 students received TOPS awards. Fewer than 27,000 received Go Grant awards.

Promise Not Immune to Budget Woes

Even some states with new programs that were hailed as successes are facing tough decisions. Oregon faces a $1.5 billion deficit for its next two-year budget. The budget crunch could pinch the state’s new free community college program, Oregon Promise.

To be eligible for the Promise program, Oregon students must earn a 2.5 high school GPA. The program is structured as a last-dollar program, meaning it is awarded after other forms of financial aid.

It cost about $12 million for a single cohort of students in its first year. But continuing it means paying for multiple cohorts of students -- new students and those that are continuing their studies. The cost for doing so is estimated at as much as $50 million over the state’s next biennial budget, said Ben Cannon, executive director of the Oregon Higher Education Coordinating Commission. The cost is also slightly higher than expected because the program was more popular than originally anticipated.

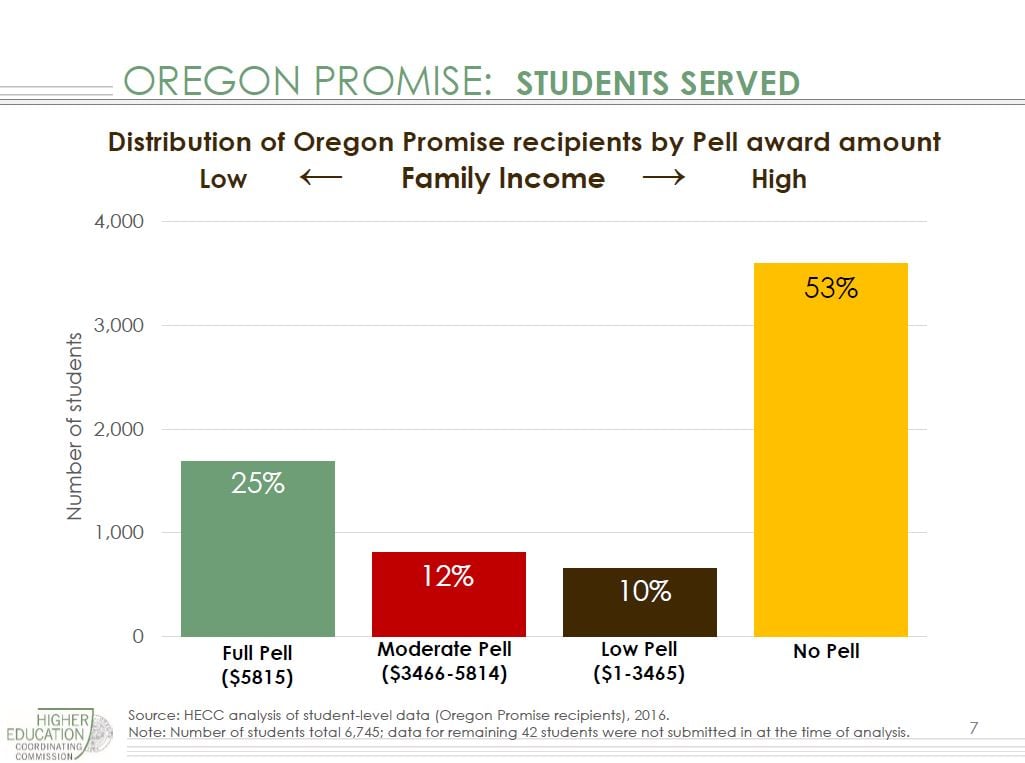

The promise has received some scrutiny after a recent report found students from higher-income families are disproportionately benefiting from it. A full 53 percent of Promise recipients did not receive Pell Grants, which are considered a proxy for students from low-income families.

Students who do not receive Pell Grants drive up the cost of the program to the state as well. The state must foot the full cost of their tuition instead of a partial cost offset by Pell Grants.

It’s possible the program could be modified to reduce student eligibility based on family income, Cannon said. The maximum award size could be capped. The $50 copay students must contribute per term could be increased. Higher grade point average requirements could be put in place.

“I don’t think the program will be eliminated,” Cannon said. “I think the Legislature will make a really robust effort to maintain it as closely as possible to what exists today as they can.”

This is far from the first time state policy makers have had conversations about aid programs, costs and priorities, said Thomas Harnisch, director of state relations at the American Association of State Colleges and Universities.

Georgia’s well known non-need-based HOPE program has been debated -- and criticized for leaving out many low-income and minority students. Florida is considering bolstering its non-need-based Bright Futures program after curtailing it during the recession. The changes would have the program pay full tuition for top students enrolling at state universities, raising concerns that they would pour money into top-tier students, who tend to be wealthy and white.

Debates could play out in different ways based on states’ individual politics and financial situations.

“Each of these programs is unique,” Harnisch said. “The challenges confronting state financial aid programs stem from eroding funding streams, higher tuition costs and a greater number of eligible students. And these forces have collectively led to budgetary shortfalls in the programs.”

Lawmakers sometimes worry about making changes to programs that affect the middle class and wealthy because those programs are popular and benefit the people who vote the most, Harnisch said. The decisions lawmakers make reveal their true priorities -- and, by extension, the programs’ true priorities.

“It comes down to a fundamental question of what you want to achieve with these programs,” he said. “And how do you best achieve it?”