You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images

As obstructionist protests of controversial speakers spread, some say the future of the trend depends on how colleges and universities respond -- namely what, if any, disciplinary action they take against participants. But just what action to take, and when, is tricky business. Practically, it can mean sorting through the chaos that often surrounds such events to find specific perpetrators; politically, it can mean wading into murky waters.

The University of Chicago has some ideas on how to proceed. Two years after the institution adopted a statement affirming free speech that has since been adapted by a number of other colleges and universities, a committee at Chicago has published a new report on discipline for disruptive conduct. The committee of faculty-led committee was charged by Chicago’s provost with reviewing and making recommendations about procedures for “student disciplinary matters involving disruptive conduct including interference with freedom of inquiry or debate” last summer -- long before Charles Murray was shouted down at Middlebury College or a controversial Canadian professor who opposes using gender-neutral pronouns was drowned out at McMaster University, for example. But its recommendations now seem prescient to some. Others find them lacking.

Perhaps most significantly, the committee recommends that disruptive conduct, which is currently addressed at Chicago within individual academic units, be covered by a centralized disciplinary process. While the committee’s hope is to provide “greater consistency across cases,” it does not propose prescribed actions for specific offenses. Rather, it seeks to create a voting committee of five members -- three professors, one student and one staff member drawn from a larger pool appointed by the provost -- to mete out discipline on a case-by-case basis. So while leaving punishments to a committee and designated administrative support office, it's clear that protests that prevent someone from talking violate university rules.

“It was clear to us in meetings on campus with students and faculty that there were a wide range of views on how speech should be approached at the university, and so we didn’t try to hardwire particular punishments,” Randal C. Picker, committee chair and James Parker Hall Distinguished Service Professor of Law at Chicago, said via email. “I expect that to play out in particular cases if we reach that point, but of course I hope that we don’t.”

The committee also proposes that the university “should revise its procedures for event management to reduce the chances that those engaged in disruptive conduct can prevent others from speaking or being heard.” Namely, it suggests naming and training “free-speech deans on call” to deal with disruptive conduct as it happens, and preauthorizing some process by which disruptive individuals can be removed from events, if necessary. Why? “The current rules, which often force deans on call to try to contact other administrators at the university in the middle of a free-speech disruption, are simply unworkable,” the committee says.

Similarly, the committee recommends that Chicago “provide greater clarity on the roles and responsibilities of hosts, speakers, audience members, event staff and the university police at events to improve understanding of the university’s commitment to free expression and clarify the consequences of disrupting the free-speech commons.” That could including creating more explicit audience guidelines, increasing staffing of deans at events and more training for other staff, according to the report.

Regarding transparency for students and other groups, the committee says that audience guidelines, along with the roles of various staff members charged with protecting free speech and the consequences of disrupting it should be readily available to students. “We recommend that the Student Manual include examples of protests that are likely to be regarded as nondisruptive as well as those that are likely to be disruptive. Nondisruptive protests include: marches that do not drown out speakers; silent vigils; protest signs at an event that do not block the vision of the audience; and boycotts of speakers or events," the report says.

Disruptive protests, meanwhile, include “blocking access to an event or to a university facility and shouting or otherwise interrupting an event or other university activity with noise in a way that prevents the event or activity from continuing in its normal course.”

When disrupters are not affiliated with the university, the committee says that they should be treated like they are part of campus life, whenever possible. When that’s not possible, unaffiliated individuals who engage in disruptive conduct “can be barred from all or part of the university permanently or for discrete periods under standards and processes,” according to the university’s existing no-trespass policy.

In terms of prevention, the committee says the university needs a more robust education program to ensure that students “understand the rights and responsibilities of participating in the free-speech commons.” It recommends new, targeted outreach measures for students and recognized student organizations, which build on existing student-centered programs and resources but are coordinated by the Office of Campus and Student Life and developed with the faculty.

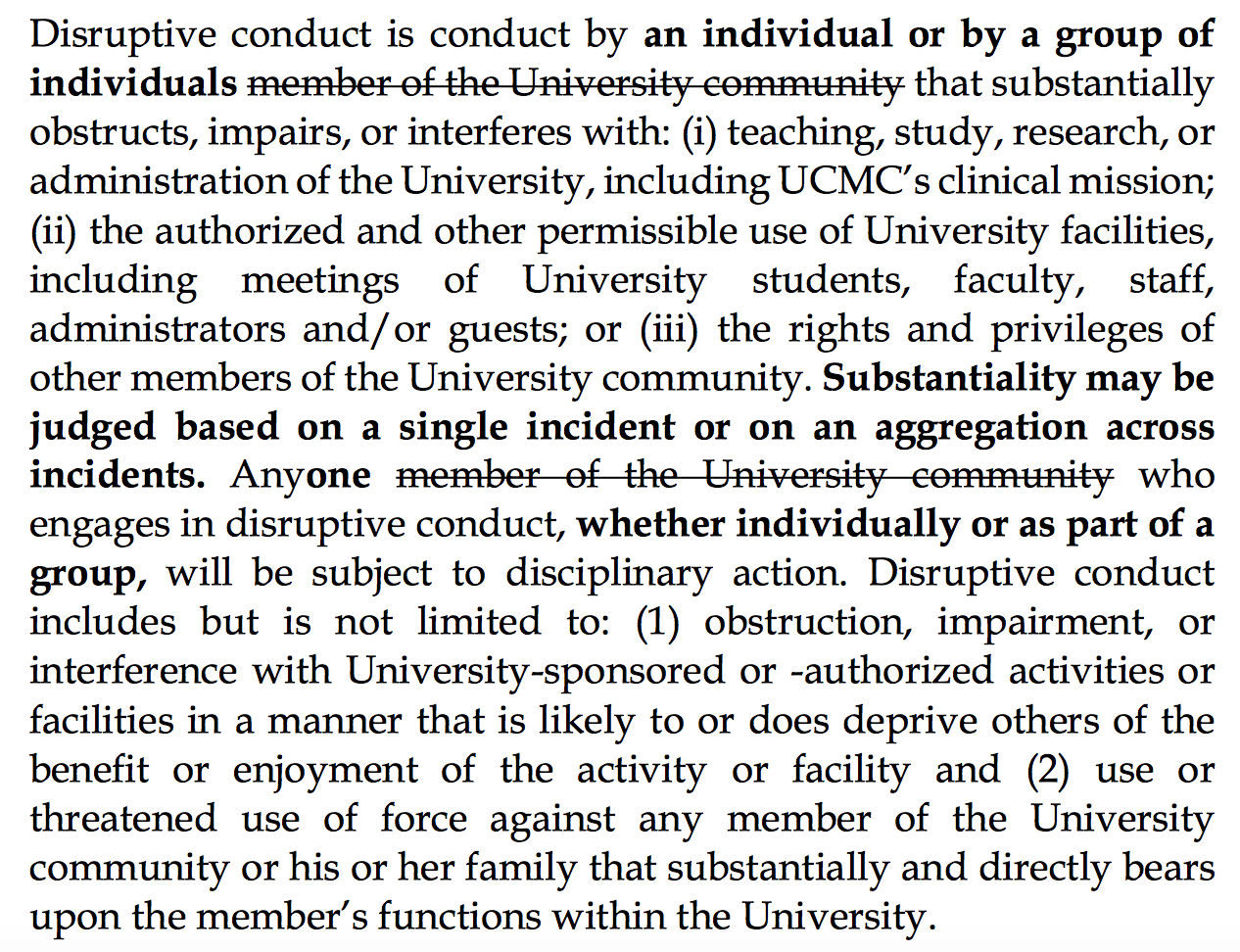

Finally, the committee recommends that the university amend an existing statute on disruptive behavior to include nonmembers of the university community, as well as members, and to clarify that interfering conduct may include behavior at one or more events. That’s because “serial conduct may in the aggregate rise to the level of disruptive conduct even if a single instance of such conduct does not,” the committee says. It also points out that disrupters may be individuals or groups.

Here is the statue, with proposed changes in strikeouts and additions in bold.

The University Council must weigh in the report before Chicago adopts it, and discussions could begin as early as this month.

The report has already received praise from some off campus. Peter Wood, president of the National Association of Scholars, wrote in the Federalist, for example, that it’s “a welcome step for all of American higher education,” since “it restores to the campus authorities charged with maintaining order the tools they need to do their jobs.” He praised the committee for recognizing that both individuals and groups may be responsible for blocking free expression or inquiry.

Robert P. George, McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence and director of the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions at Princeton University, and co-author of a recent statement denouncing those who interfere in campus speech, also approves. He said in an interview with Inside Higher Ed that the report’s value will ultimately hinge on the consistency and "content neutrality" with which discipline is administered -- meaning, for example, that a person who shuts down a pro-Israel rally should be punished similarly harshly to one who shuts down an anti-Israel one. Otherwise, he said he wasn’t really “in the mood to criticize this kind of moral seriousness and leadership.”

Once again, George said, referring to the 2015 statement on free speech, which Princeton promptly adopted, “Chicago has taken the lead in ascending core academic values. … They’re thinking about how to put teeth in the obligation of everyone on campus to respect the rights and freedoms of thought and expression of everyone else on campus.” He said he hoped other institutions would follow suit.

John K. Wilson, an independent scholar of free speech and co-editor of the American Association of University Professors’ “Academe” blog, shredded the report in a post, however. While he approves of a centralized disciplinary system, Wilson wrote that the report as a whole “fails to address serious problems with free speech and due process in Chicago’s rules, and mostly makes proposals to reduce free expression on campus by aiming to suppress protest.”

Among other criticisms, Wilson wrote that the committee offers definition poor definitions of misconduct, including, to quote the report, “blocking access to an event or to a university facility and shouting or otherwise interrupting an event or other university activity with noise in a way that prevents the event or activity from continuing in its normal course.”

There’s a “fundamental difference between ‘interrupting’ an event and shutting it down,” Wilson says. “A protest can disrupt the ‘normal course’ of an event without preventing it from continuing altogether.” He also disapproves of the notion of cumulative offense, saying that if "a single incident does not justify punishment, then repetition of it at different events should not be punished." And if the statute is indeed changed to potentially allow for assigning penalties “individually or as part of a group," he says, it suggests that "if a person is part of a group that breaks the rules, even if the individual doesn’t, that person can be punished."

Picker, the committee chair, said Wilson’s critique includes pre-existing policies, not just those his group suggests. Wilson said he does disagree with Chicago's approach to such issues, not just the committee's. But the new report is problematic on its own, he said, and the committee should have urged bigger changes to the statute -- like getting rid of it.

The committee says its work was primarily informed by two university values enshrined elsewhere, in previous reports on free speech (including that from 2015). First, Chicago's "fundamental commitment is to the principle that debate or deliberation may not be suppressed because the ideas put forth are thought by some or even by most members of the university community to be offensive, unwise, immoral, or wrong-headed." Second, “[d]issent and protest should be affirmatively welcomed, not merely tolerated."