You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The federal government gives up more revenue for higher education-based income tax deductions, credits, exclusions and exemptions than it spends on Pell Grants -- and states extend many similar tax breaks to students.

Yet many state lawmakers are effectively flying blind when it comes to the amount of money they’re putting into higher education-related income tax breaks, according to a report released Wednesday by the Pew Charitable Trusts. While state spending on line items like operating support for public colleges or grants paid to support students is typically quantified and debated by legislatures regularly, tax code changes are put in place and then largely ignored in subsequent years of budgeting. Pew could not even obtain estimates from a majority of states for the amount of revenue they forgo because of higher education tax benefits for students and families.

In other words, policy makers aren’t getting the full picture as they try to decide on the best way to fund their higher education goals, according to Phillip Oliff, manager at the Pew Charitable Trusts fiscal federalism initiative.

“Our analysis suggests many state policy makers lack important information on tax expenditure costs that they would need to paint that full picture,” Oliff said during a conference call on the report results. “States should consider how they might provide more thorough estimates of these costs.”

The Pew report looked at federal higher education tax benefits that allow students and families to cut their income tax liability but also cut into government revenue. Additionally, it examined state higher education tax benefits and the way tax benefits at the different levels of government are related.

Federal and state tax benefits typically aim to give a tax break to families who are saving for college, paying for classes or paying off college loans. Well-known examples include 529 plans for saving for college, the federal American Opportunity Tax Credit that allows a maximum annual credit of $2,500 per student for education expenses, and the deduction for interest paid on student loans.

The amount of money governments decide to forgo matters in part because some believe that certain tax breaks tend to benefit middle- and upper-income students who can afford to go to college without deductions in the tax code. The money potentially collected from such students could be better spent in other ways, like grants to low-income students or to fund university operating expenses, the argument goes.

Further, since government grant spending that tends to benefit low-income students is more visible to policy makers than tax breaks are, many believe grant spending is more likely to be cut back during times of budget crunches -- effectively meaning the poor lose government support while the middle class and wealthy are protected during economic downturns.

Pew’s report does not wade into the details of that dispute.

“However, tax expenditures generally benefit households across more income levels than Pell Grants do,” it says.

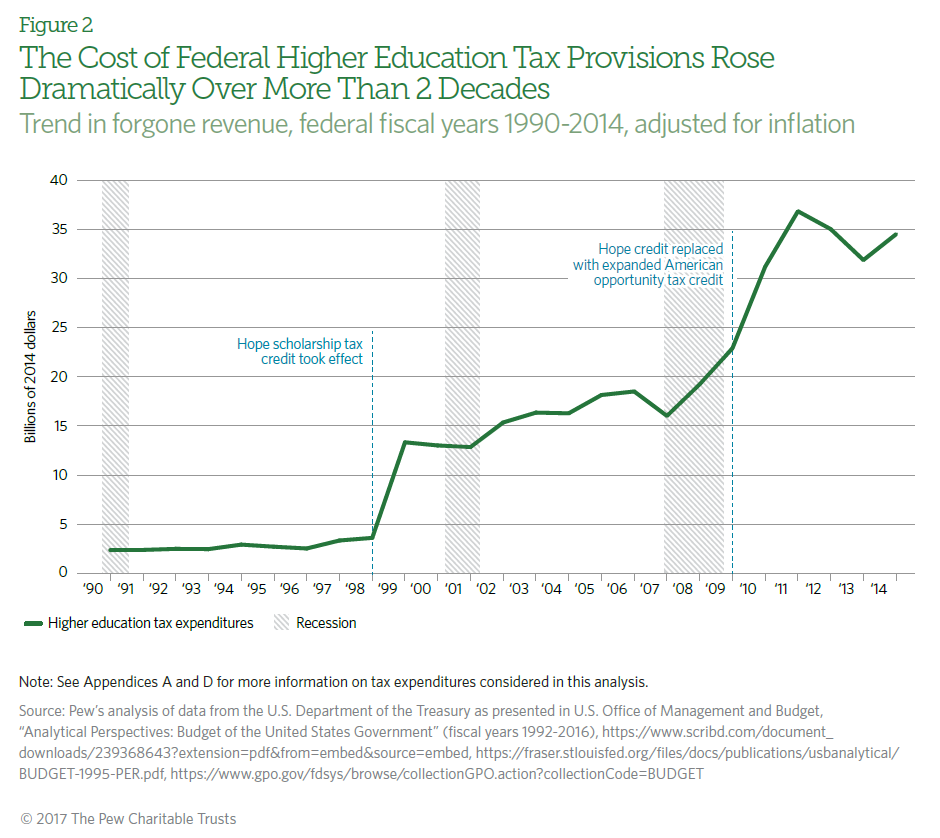

At the federal level, the government did not collect $34.5 billion in income tax revenue in 2014 because of tax code benefits for students and families, Pew found. That’s 14 percent more than the $30.4 billion the government spent on need-based Pell Grants for low-income students. It is also a sizable amount when compared to the $75 billion in total federal spending on higher education -- a number that includes Pell Grants, other financial aid grants, research grants and veterans' educational benefits but that does not include student loans.

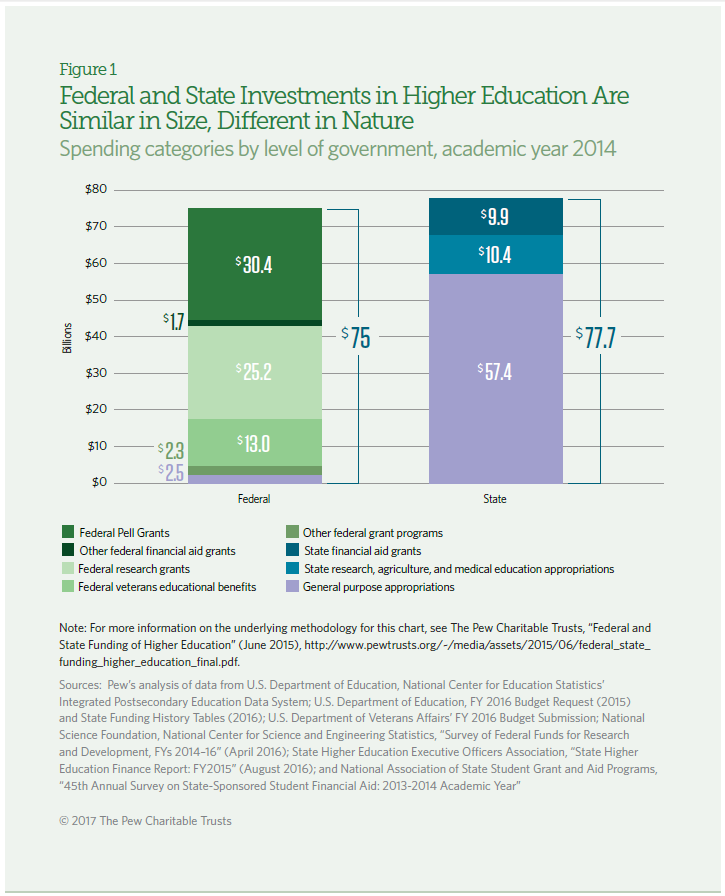

The Pew report also notes that higher education tax benefits cost the government dramatically more today than they did a quarter of a century ago. Federal revenue forgone because of higher education-related income tax breaks totaled $2.4 billion in 1990, after adjusting for inflation. Since then, such uncollected revenue has grown by about 13 times to $34.5 billion in 2014, the last year for which data were available.

Two major periods of growth can be traced to a scholarship tax credit. The Hope scholarship tax credit went into effect in 1998. It was renamed the American Opportunity Tax Credit and expanded in 2009.

Federal tax benefit growth is unlikely to stop any time soon, according to Robert Kelchen, an assistant professor of higher education at Seton Hall University who studies finance and student financial aid. The benefits aren't generally popular with academics, many of whom would rather see money spent on grant aid to students, but they do have many supporters.

Even if a tax reform or simplification package that cuts down on higher education benefits were to pass in Congress, it might not lead to a shift of money from higher ed tax benefits to grant funding for students.

"It’s worth emphasizing that tax benefits and Pell Grants come out of different Congressional committees and effectively come out of different pots of money," Kelchen said in an email. "Many proposals to reform higher education finance end tax benefits, but there is no guarantee that savings would actually go to the Department of Education (particularly in this administration)."

The $34.5 billion in federal revenue forgone because of higher education-related tax breaks is also sizable in comparison to state spending on higher education. States spent just over $77.7 billion in 2014. A vast majority of that spending, $57.4 billion, went to operational support for public higher education institutions. Other state spending went to financial aid grants and appropriations for research, agriculture and medical education.

No broad conclusions can be drawn about how much revenue states forgo because of higher education income tax benefits for students and families, Pew found. Washington, D.C. and 41 states levy broad-based personal income taxes. All of them provide some type of higher education tax benefit for filers, Pew found. Still, data were difficult to obtain.

“Pew was able to obtain cost estimates covering at least two-thirds of the relevant expenditures from only nine states and the District, and in some of those states, the estimates are not produced annually,” the report says.

For states where data was available, the report compared estimated uncollected revenue and compared it to financial aid grants awarded. Revenue not collected because of higher education-related tax benefits exceeded 25 percent of financial aid awarded in all states but one. Massachusetts had the highest ratio, not collecting $121 million in tax revenue and spending $91 million in financial aid. Georgia posted the lowest ratio, not collecting $44 million in tax revenue and spending $570 million in financial aid.

| State | Estimated forgone revenue from tax expenditures (in millions) | Financial aid awarded (in millions) | Forgone revenue compared with financial aid grants |

|---|---|---|---|

| California (fiscal 2012) | $443 | $1,495 | 30 percent |

| District of Columbia (fiscal 2014) | $9 | $32 | 29 percent |

| Georgia (fiscal 2014) | $44 | $570 | 8 percent |

| Massachusetts (fiscal 2014) | $121 | $91 | 133 percent |

| Minnesota (fiscal 2014) | $51 | $182 | 28 percent |

| Missouri (fiscal 2011) | $26 | $91 | 29 percent |

| New York (fiscal 2013) | $457 | $973 | 47 percent |

| Oregon (fiscal 2014) | $48 | $55 | 87 percent |

| Pennsylvania (fiscal 2014) | $167 | $459 | 36 percent |

| Wisconsin (fiscal 2014) | $88 | $129 | 68 percent |

Many of the states’ higher education tax benefits are connected to those of the federal government. Many states -- 38 plus D.C. -- allow filers to claim a dependent exemption for full-time students who are ages 19 to 23, a benefit based on federal rules. Most states also use a federal definition of income in their own tax calculations -- and that definition covers several federal exclusions, like investment earnings from 529 college savings plans, and deductions, like interest paid on student loans.

While a handful of states specifically disallow at least one federal higher education-related income tax benefit, more than half of those that link to the federal definition of income permit all federal provisions without modification, according to Pew.

That’s a particularly important point now as President Trump and Congressional Republicans spark talk about broad federal tax reform. Any changes made at the federal level would potentially have major effects on states as well.

“While we don’t have a crystal ball, it’s important to keep in mind that any changes to federal provisions could have an impact on states, forcing them to decide whether to adopt those changes into their own tax codes or decouple from those provisions,” Oliff said.

Not every state tax benefit is tied to the federal government, however. For instance, in New York, students and families can choose a tax credit or deduction for tuition and fees paid that is not connected to the federal tax code. Those credits and deductions represented $240 million in lost revenue in 2013.