You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

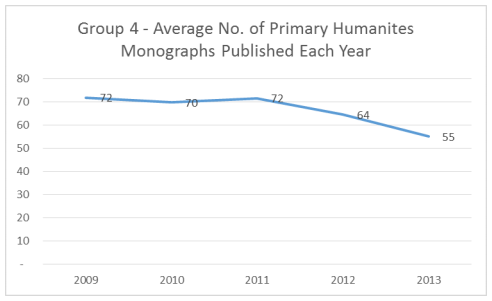

The market for original humanities monographs may be shrinking, according to a report on the output of university presses.

After remaining stable from 2009 to 2011, the number of original works in the humanities published by university presses fell both in 2012 and 2013, according to estimates made by Joseph Esposito and Karen Barch, the two publishing consultants who wrote the report. Their numbers suggest presses on average published an estimated 70 such books a year between 2009-13, then 64 in 2012 and 55 in 2013.

The report, which was funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, is an attempt to quantify how many books university presses publish a year. The authors surveyed 106 presses and received responses from 65 of them, a sample from which they extrapolated that the presses published about 76,000 books between 2009-13, or about 15,000 books a year. About 3,000 of them are primary humanities monographs.

The findings come with some significant qualifiers, Esposito said in an interview. For one, the authors do not feel comfortable concluding that the market is in decline based on two years’ worth of data. Additionally, reporting issues may have skewed the results. One major university press showed “remarkable falloff” in the data it submitted for 2012 and 2013, which Esposito said could have been an error on the press’ part.

“If you look at the data over five years, you see a modest decline,” Esposito said. “The issue there is that is five years enough time to make a generalization like that?”

If the market is in decline, it could be a sign that the university presses that publish those monographs are struggling -- and indeed many presses have closed or scaled back their operations in recent years. Earlier this month, for example, Duquesne University Press said it would close later this year. The press specializes in fields such as Continental philosophy, humanistic psychology and medieval and Renaissance literature studies.

But it could also hint at changes taking place in tenure and promotion processes in the humanities. While many scholarly associations have urged departments to expand beyond the monograph as the measure for tenure worthiness, many junior scholars report little change in attitudes, great pressure to publish monographs and a tough time doing so.

Peter Berkery, executive director of the Association of American University Presses, said in a statement that the organization hasn’t heard anything from its members to suggest the market is shrinking. He said more data are needed before any conclusion about publication trends can be drawn.

Roger C. Schonfeld, director of the libraries and scholarly communication program at Ithaka S+R, a research and consulting group, echoed that sentiment. He said in an email that he did not wish to speculate about whether the decline in publishing output has continued beyond the authors’ data cutoff point.

“With relatively few years of data, it is hard to draw strong conclusions about any possible ‘decline’ in the market, especially given that there are other publishers of humanities works beyond the university presses studied in this project,” Schonfeld wrote, adding that he has not seen data that either corroborates or counters the white paper’s findings. “Even so, these figures can serve as an opportunity for reflection and assessment by the university press community, where many strong leaders have for some time been developing new models in support of humanistic scholarship.”

The Mellon foundation, for example, is one of the forces supporting digital scholarship in the humanities, and has for years funded projects in that space. Open-access book publishing is only one example -- other projects have explored more radical ways of rethinking what form digital-first research in the humanities should take.

Alan Harvey, director of the Stanford University Press, was also hesitant to describe the white paper’s findings as evidence of a shrinking market for humanities monographs, but said a potential decline could be attributed to strategic shifts.

Harvey said in an email that a potential decrease in output in humanities publishing could be the combination of several factors, including a shift away from limited-sale monographs, an expansion of discipline coverage and a growing interest in trade publishing.

“[W]e now work extremely closely with all our authors to ensure the broadest possible readership for their book,” Harvey wrote. “There is no dumbing-down, but instead an editorial effort to aid the author in structuring their argument in a style accessible to an intelligent, inter-disciplinary audience. The result of this is almost certainly that fewer books are being classified as ‘monographs.’”

Looking to the years ahead, Harvey said he expects to see a “blended market” with physical and digital books co-existing.

“Recall that 10 years ago we were convinced ebooks would dominate, but instead today we see a blended print and ebook market,” Harvey wrote. “I think monographic research in 10 years will similarly have a range of concurrent models for distribution. Our mission as a university press is to aid in this transition.”