You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

University of Kentucky

It’s a rare move for a state flagship university: the University of Kentucky is stepping back from the merit-aid rat race.

The university recently said it will seek a dramatic shift in its split between what it calls institutional merit aid -- also called non-need-based aid -- and need-based aid. That split is currently 90 percent in favor of non-need-based aid. By 2021, the university hopes to skew it largely the other way, to be 65 percent need-based aid.

That move would be a break from trends among many institutions, particularly state flagships, which in recent years have typically thrown financial aid dollars at top students who are viewed as likely to graduate and to bring impressive test scores that may boost ratings -- but are often more likely to be able to afford college on their own. UK’s administration lists various reasons for the change, including that it better serves the needs of Kentucky’s population and that as a land-grant institution, the university should prioritize access for students who need financial assistance.

But leaders also tout data-driven reasoning behind their goal. They’ve found that their students become much more likely to drop out if they have $5,000 or more in unmet financial need. By focusing on reducing students’ unmet need, they hope to drastically boost retention.

Their effort will likely be watched around the country as demographic projections indicate relatively fewer traditional, wealthy, elite students will be available for universities to recruit in coming years. Some critics have also criticized non-need-based aid as a race to the bottom that’s already played out with negative results, prompting bidding wars on wealthy students who will land in a good spot regardless of receiving a generous aid package.

Early reactions to the university’s plans have been positive. But unintended consequences could crop up. The wealthiest, best-prepared prospective students will not receive as much aid for coming to the University of Kentucky in coming years as their predecessors did, which could dissuade them from enrolling. Provost Timothy S. Tracy is up front about saying that the move will likely lead to a drop in National Merit Finalists attending Kentucky.

“We don’t know all the answers,” Tracy said. “We don’t know how this is going to turn out, but we believe that for Kentucky, this is the right thing to do.”

The overriding bet is that the effort helps more students stay enrolled, improving the university’s graduation and retention rates. Improving graduation rates was one of the top reasons UK gave when it announced the shift in financial aid policy in October, listing it along with several other changes targeting higher student success. Tracy and UK President Eli Capilouto have continued to write about the strategy and the reasoning behind it, breaking down the split in unmet financial need between students who stayed at the university and those who did not.

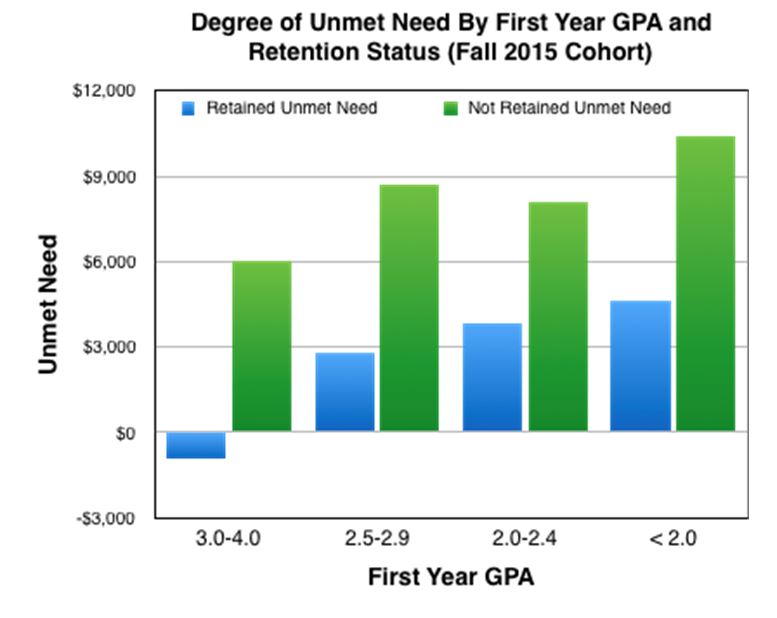

In the university’s fall 2015 cohort, first-year students who posted a first-year grade point average of 3.0 or higher and were retained had negative unmet need -- they received surplus funding. Students with grade point averages in the same range who were not retained had unmet need averaging about $6,000. Even among students posting lower grades, those retained had significantly lower unmet need than those who did not return to campus.

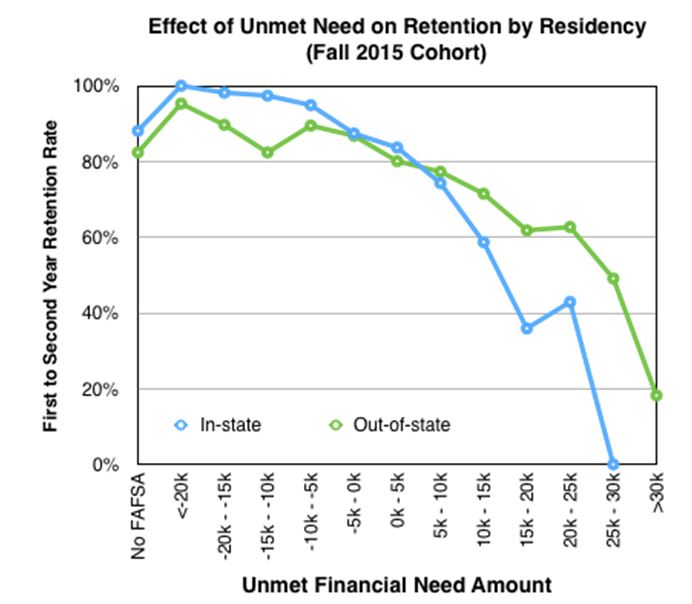

Looking at it a different way, retention rates drop as unmet need rises -- especially above the $5,000 mark. The university is defining unmet need as need remaining after a student’s expected family contribution as well as institutional, state and federal aid.

At the same time, the university, which enrolls roughly 30,000 students, has a large population whose unmet need falls between $5,000 and $15,000. Those with unmet need falling into the $5,000-10,000 range make up 14.3 percent of students. Those with unmet need in the $10,000-15,000 range make up 8.6 percent of students.

“If you look at that distribution, we saw a hollowing out of the middle,” Tracy said. “The real place where you see the most is the $5,000-10,000 and $10,000-15,000 ranges. And that’s where we want to make sure we focus.”

It’s not possible to say exactly where the final financial aid numbers will fall. But UK estimates that if the new strategy had been in place for its current first-year class, more than $17 million of financial aid would have been awarded based on need and $8 million would be based on merit and other factors. That’s a sharp difference from the actual distribution for this year’s first-year class, which saw more than $22 million dedicated to non-need-based aid.

The actual aid changes will take time. Need-based aid will grow to about 20 percent of the institutional aid budget for the class entering in the fall of 2017. The university will move the bar up toward 65 percent gradually over the next several years. Scholarships for current students won’t be affected.

The new aid strategy fits into a university goal to boost its six-year graduation rate to 70 percent by 2020, up from a current 63.4 percent. It also fits into a goal to improve the first-year retention rate to 90 percent by 2020, up from 82.7 percent among the 2014 cohort.

Modeling suggests underrepresented students will be helped by the new aid policy, Tracy said. Underrepresented students tend to have more unmet need.

Administrators are preparing for some pushback from top-level students and parents who may compare smaller aid packages to an older sibling’s or friend’s. There could be a substantial number of those students, as 37.2 percent of UK’s current students have unmet need of zero to $5,000, and 20.6 percent have unmet need of zero to negative $5,000.

The strategy doesn’t mean no aid for high-scoring students -- Tracy pointed out that top-performing students often still have unmet need. Yet he acknowledges Kentucky might lose some elite students.

“Our modeling suggests that we will probably have fewer National Merit Finalists,” he said. “We had 105 this year.”

While Tracy said UK is proud to have so many National Merit Finalists, he also pointed out that they’re 2 percent of the university’s first-year class of 5,100 students.

He believes the shift in aid strategy can be accomplished without increasing the overall financial aid budget. But he also hopes it will help UK grow that aid budget.

“We are making a major effort to take this program to our donors,” Tracy said. “It will be a major focus of what we do in the next five years for our philanthropy.”

The aid shift is one of several changes the university is putting into place under an initiative it’s calling UK LEADS -- Leveraging Economic Affordability for Developing Success. The university is also looking at other areas administrators believe are tied to student success: academic preparation, student health and wellness, and student community building. For instance, the university is evaluating applicants with a new formula that skews more heavily toward high school grade point average over standardized test scores than it has in the past. It’s also adding counselors and academic advisers.

Still, the university’s aid changes are likely its most notable. They come after decades during which public and private institutions shifted institutional aid toward non-need-based awards in order to attract the most academically prepared students, said Rosemaria Martinelli, a senior director with Huron Consulting Group’s higher education business. Martinelli and Huron work with the University of Kentucky.

“With declining demographics across the nation, schools are now focused on initiatives aimed at improving student retention,” Martinelli said in an email. “Shifting institutional dollars focused on merit to need-based aid is one strategy that has been found to be successful, particularly for students where large unmet need has been found to be one of the barriers to student success.”

Other consultants report high interest in student retention, aid and unmet financial need. Bill Hall, the founder and president of Applied Policy Research Inc., a consulting firm specializing in enrollment management, says financial aid has shifted over the last 15 years toward incentivizing middle-income and upper-middle-income students. Non-need-based aid offers increased noticeably during the recession at both public and private institutions. They were putting their money into students they were sure they could retain, Hall said.

An unprepared student is still at the greatest risk of attrition, Hall said. But APR has zeroed in on financial aid and need as well. Its analyses have generally found that $7,000 of unmet need is roughly the point at which student retention drops. That’s slightly higher than the University of Kentucky’s $5,000 mark, but as a public institution with sticker prices below those of private institutions, UK might attract students who are more price sensitive.

“Anything in that $5,000-7,000 range is getting in that danger zone with respect to unmet need,” Hall said. “It’s even more sensitive with first-generation students.”

The question of how much unmet need is too much is the right one to ask, according to Matthew Chingos, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute. He believes it is sensible to ask which students need the most help and which ones are most likely to graduate if awarded financial aid.

Dedicating large chunks of budgets to non-need-based aid can be tempting for states or institutions that want to compete for top students, Chingos said. But when many institutions are pursuing that strategy, it can lose its effectiveness as students with high grades receive multiple lucrative financial offers.

“You probably end up writing a whole lot of checks to people who would have stayed in the state anyway,” Chingos said. “That’s basically wasted money.”

Observers of higher education in Kentucky say additional factors have enabled UK’s move to change its aid policies. Kentucky is moving toward a performance funding model that places a premium on degrees earned by low-income and minority students, said Robert L. King, president of the Kentucky Council on Postsecondary Education. UK’s shift has also been made possible by the fact that it has improved its academic reputation in recent years, he said.

“What that’s doing is reducing the pressure on the so-called merit aid to try and buy students to come there, which I think is a good sign,” King said. “I think they’re seeing that they can be more selective and at the same time devote more of their resources to those students who really need them.”

The emphasis on lowering unmet need also matches what professors are seeing on the ground. John R. Thelin, a university research professor at the University of Kentucky and the author of A History of American Higher Education, said he is partial to the strategy of need-based aid and trying to assist students from modest backgrounds. But outside that, he said he was hearing stories about undergraduates dropping out of the University of Kentucky because they could not afford to stay enrolled.

“About a year ago, I was teaching a seminar, and it had graduate students who worked in financial aid and student affairs,” Thelin said. “What they were all emphasizing was that there were substantial numbers of low-income, modest-income students who were doing well academically and were dropping out. And it was due to a relatively small amount of money.”

UK’s faculty members have generally been supportive of the new strategy, said Katherine McCormick, a professor in interdisciplinary early childhood education who chairs the University Senate. Instead of having one exceptional student in class, they may have four or five strong students, she said.

“That idea of having more students who are high-quality students who will be engaged, to have five or six of those rather than only one is a real selling point,” she said.

If the effort is successful at boosting retention, it could also increase the number of students taking higher-level classes. Faculty members would welcome that as well, McCormick said.

“That retention effort might really pan out,” she said. “It’s often a good mix if you have a chance to grow your own program.”