You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Wage data are a key part of the bipartisan push to give prospective students more information about the value of a college credential. But measures of graduates’ earnings can be of limited use to the large number of people who lack choices about where to go to college.

That’s the central finding of a new study from researchers at the Urban Institute. The paper, dubbed “Choice Deserts,” looks at how geography and academic selectivity curb the impact of earnings data for students in Virginia.

The U.S. Department of Education recently included information about graduates’ wages in its College Scorecard. And a growing number of states have created similar, consumer-facing figures, sometimes with help from College Measures, a company that produces student outcomes data.

Less reliable but also popular, particularly with the news media, is earnings information from PayScale, a website that tracks self-reported earnings of former students.

The idea behind these consumer tools is that prospective students can see median wages of graduates of specific academic programs and then use the data to make a more informed choice from among the several thousands of colleges and universities in the country.

Yet many, if not most, students attend a college near their home.

Previous research has found that community college students attend an institution that is an average of 31 miles from home -- and a median distance of eight miles. Students at four-year institutions are 82 miles away on average, with a median distance of 18 miles.

Likewise, many of these students live in what the Urban Institute paper calls education or choice deserts, with no or few academic programs in their preferred field of study, at least ones offered by colleges that stand a good chance of accepting that student.

Tod Massa, the director of policy research and data warehousing for the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia, has written about this issue. He said the new report reaches a similar conclusion.

“Place-bound students are not necessarily affected by program-level wage comparisons in the way policy makers might think,” Massa said via email. “There is too often an assumption that all students are equally mobile in their choice of college.”

The Urban Institute study analyzes the usefulness of programmatic earnings data in Virginia, which has one of the most sophisticated state-based student outcomes databases. Matt Chingos, a senior fellow at the institute, and Kristin Blagg, a research associate there, wrote the paper. They analyzed the numbers of available programs with public earnings data for eligible students within 25 or 50 miles of their home.

On average across academic programs, most Virginia students either live in an education desert (21 percent) or somewhere without meaningful earnings information (42 percent). Just 36 percent of students can make a truly informed choice based on meaningful earnings data, the study said. (Note: This paragraph has been changed from a previous version to correct a reference to the context of these numbers.)

Among the 38 Virginia colleges that offer a bachelor’s degree in business management, for example, just 29 percent of students who are eligible to attend only less-selective colleges can make an informed choice about those programs within 25 miles of their home, according to the research. The rest live in some version of an education or choice desert.

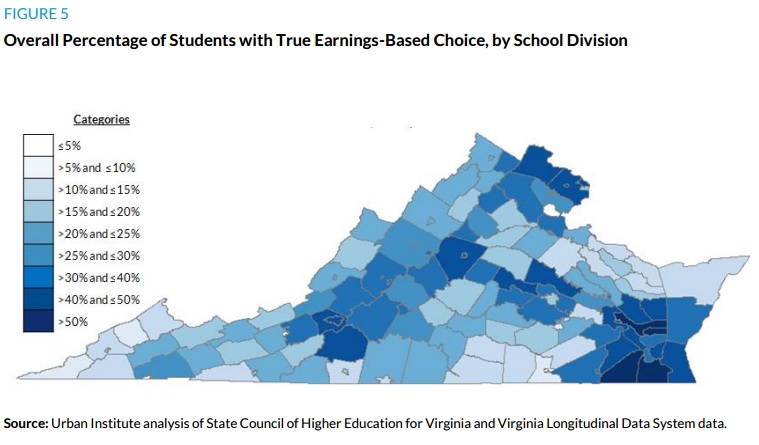

In contrast, 63 percent of more academically prepared students, who are eligible to attend selective colleges, can use earnings data to make a true informed choice -- with earnings data that provide meaningful comparisons -- about a bachelor’s degree in business management within a 25-mile radius from their home, the study found. And students with more choices tend to live near cities like Washington, Richmond, Charlottesville and Lynchburg, according to the paper (see graphic below).

Increasing the distance to 50 miles that students are willing and able to travel to attend college changes those numbers. For example, 75 percent of students headed to a less-selective college within a 50-mile radius that offers a business management B.A. had a truly informed choice, the study found, compared to 97 percent of students who are eligible to attend a selective college.

Value, With Limitations

The study comes with some limitations. Not all academic programs have good earnings data, the researchers note. Just seven of the state’s 35 bachelor’s degree programs in mathematics yield wage information.

In addition, the study uses data on high school seniors, not for the large number of older, financially independent students. It also does not factor in the role of online programs to potentially counteract geographic limitations.

Perhaps most importantly, the researchers said prospective students can glean value from earnings data for reasons other than comparing colleges.

“For example, a student might use earnings data to help select a major after enrolling at a particular institution,” the study notes. “Many students enter college unsure of their academic plans, so earnings data provided at the right time could inform decisions about what field of study to pursue.”

This is an important distinction, said Mark Schneider, president of College Measures and a vice president at the American Institutes for Research. Prospective students often are mulling what to study as well as where to go to college, he said, including place-bound students.

“I have many programs in that college that I can choose from,” Schneider said of a prospective student who is looking at wage data. “I could in fact compare that program to the state average or to other schools.”

The new study also said earnings data have policy value, particularly when state lawmakers use them to encourage the creation or expansion of academic programs with job-market value in underserved areas.

While some critics say this approach embraces an overly vocational view of higher education, few would argue that career results are not an important part of trying to measure what a college experience should provide.

“Policy makers should not abandon their efforts to enable prospective students, policy makers and the public to assess colleges and universities based on data on student outcomes rather than reputation and vague impressions from campus tours,” the study said. “But our findings suggest that this approach’s potential to improve the market for higher education likely lies in the other efforts it makes possible and not in the inherent usefulness of publishing earnings data.”

Likewise, Massa and others caution against prospective students leaning too heavily on earnings information when choosing a program.

“I would never suggest a student pick a program or degree solely on wage outcomes,” he said. “Instead, they should use outcomes to inform themselves about what previous graduates have earned, and what that may suggest for themselves.”