You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Findings released Thursday from the National Survey of Student Engagement suggest that one in seven black students feel physically unsafe on college campuses.

Overall, 93 percent of the 13,000 students who responded to the survey reported feeling physically safe at their institution, but that perception varied among different demographic groups. Among black students, 14 percent said they disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement “I feel physically safe at my institution.” One in 10 American Indian or Alaska Native students and 9 percent of multiracial students also said they disagreed or strongly disagreed with that statement.

About 5 percent of white students reported feeling unsafe, as did 5 percent of Hispanic or Latino students, and 6 percent of Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander students.

“The good news is that the vast majority of students do feel safe on campus,” Alexander McCormick, director of NSSE, said. “But there are still feelings of alienation and disconnectedness out there that we should be concerned about. There is an emotional cost and strain to not feeling safe or welcome that gets in the way of studying and engagement.”

The findings, based on responses to a survey administered this spring, come at a time when many minority students are reporting racial incidents on numerous campuses following the election of Donald Trump as president.

At the University of Pennsylvania last week, for example, black freshmen started to receive messages from GroupMe, a group text messaging service, from an account called “Daddy Trump” or “Heil Trump.” The messages included racist slurs, violent images and information about a “daily lynching.” The messages were sent from students in Oklahoma.

“One can’t help but wonder what the responses would be now, with some of the incidents after the election,” McCormick added.

In response to these incidents and Trump’s victory more generally, some professors postponed exams or canceled classes, and many colleges reminded students of the counseling services available to them. Noting that “partisan, inflammatory statements” can cause “real wounds,” Northwestern University’s vice president for student affairs, Patricia Telles-Irvin, said in an email that the university recognizes “the need for healing of those wounds,” and that officials “want to extend support to those students who are experiencing difficulty at this time.”

Education Secretary John B. King Jr. urged university leaders Tuesday to be sure that students do not feel harassed or intimidated in the wake of a divisive election that has left "many of our students feeling vulnerable." Speaking in Austin at the annual meeting of the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities, King said that all students -- regardless of race, gender, nationality, sexual orientation or gender identity -- deserve to be treated with respect. Higher education leaders need to send "a clear message," he said, that campuses will not tolerate harassment, that "diversity is a value" and that they will "respond aggressively to places where safety is violated."

Such efforts by institutions have been met with criticism from observers who say colleges too often coddle and shelter their students from the real world.

“Make no mistake: Our universities are teaching you to feel hurt or traumatized,” Jonathan Zimmerman, an education and history professor at the University of Pennsylvania, wrote in the New York Daily News on Friday. "Let me be clear: mental illness is real, and of course our institutions should offer health services to anyone who is suffering from one. But we mock real psychological injury when we speak of every slight or disappointment as a 'trauma,' which is a clinical word we should reserve for truly debilitating events. And we encourage students to feel incapacitated, which is the last thing they need at moments like this one."

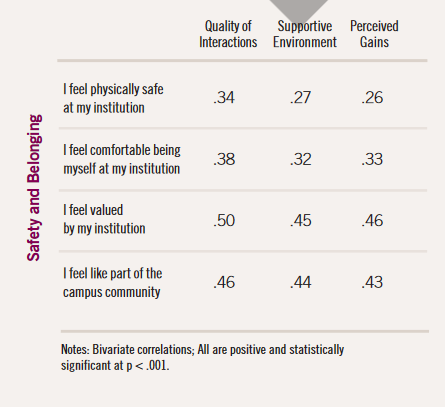

Shaun Harper, executive director of the University of Pennsylvania's Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education, said educators would be mistaken to dismiss how students feel -- whether they feel safe, or feel valued, or feel like a member of the campus community -- if their goal is to improve students' learning. This year’s NSSE findings touch on that idea, as well, suggesting that there’s a correlation between feelings of safety and belonging and student outcomes.

According to the report, students who reported that they felt safe, comfortable being themselves, valued and part of the community had more positive interactions with others on campus, perceived greater intuitional support and believed more strongly that their college promoted their growth and development.

According to the report, students who reported that they felt safe, comfortable being themselves, valued and part of the community had more positive interactions with others on campus, perceived greater intuitional support and believed more strongly that their college promoted their growth and development.

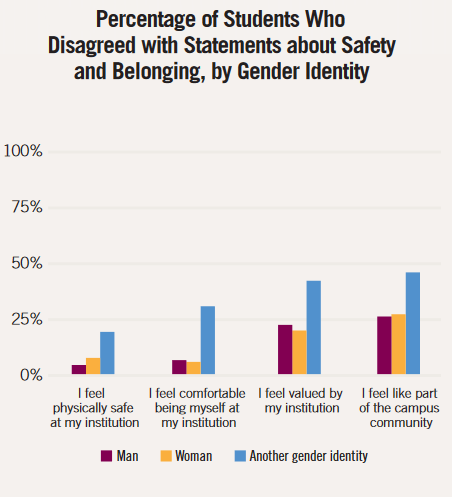

Most students in the survey -- about 75 percent -- reported feeling “like part of the campus community,” but a significant percentage said they disagreed or strongly disagreed with that statement. Nearly 40 percent of American Indian or Alaska Native students reported feeling like they didn’t belong, as did 31 percent of multiracial students and about a quarter of black, Asian, Hispanic and white students.

Transgender students and students with a gender identity other than man or woman were twice as likely to disagree with positive statements about safety and belonging than their cisgender peers.

“Colleges and universities just don’t do a good enough job of intentionally building a community that affirms students and their identities,” Harper said. “If we don’t listen and take seriously what people are saying about their feelings, then bad things happen. People become disengaged and disconnected form the educational experience, which results in bad academic performance, which ultimately compels them to drop out. That’s a serious thing we have to pay attention to. Some people would look at these findings and see it as good news. But just because 80 percent feel valued, that doesn't mean we can just write off the other 20 percent. If even just one student doesn't feel valued and safe, that's affecting academic performance.”

Support for Struggling Students

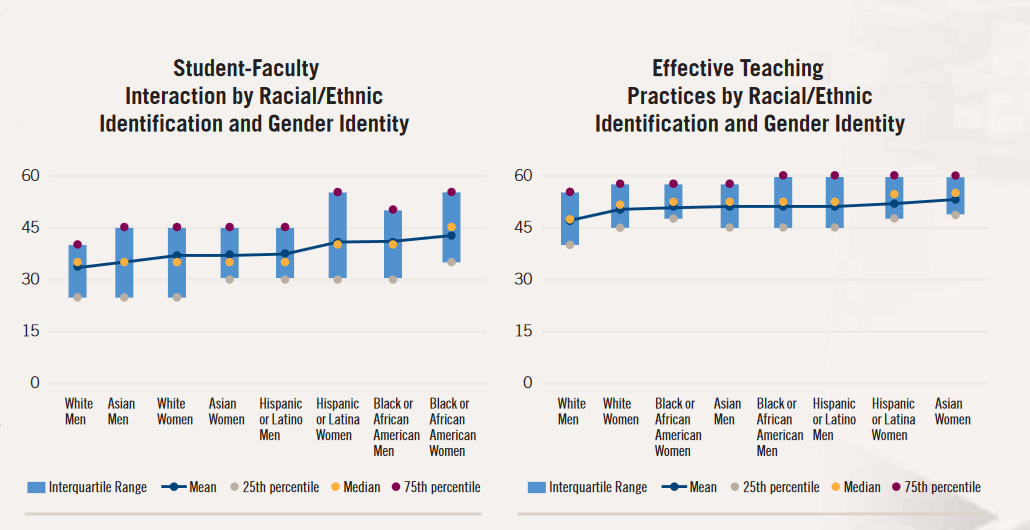

As part of the 2016 Faculty Survey of Student Engagement, NSSE’s companion survey for faculty members, the researchers also asked 14,500 instructional staff about their teaching practices. Though there was great variation among instructors from any demographic, the survey found that, overall, “Black or African-American men and women interacted most often with students in meaningful ways, while white and Asian men did so the least.”

The survey measured these practices by asking instructors how often they had discussion with students about career plans, course topics and academic progress, and how often they have worked with students on non-course-related activities such as committees and student organizations. The survey also included questions about providing “timely and detailed feedback” and “a variety of teaching techniques,” such as clearly explaining course goals and providing feedback on in-progress course work.

That level of support can be especially important for minority and first-generation students, McCormick said.

One in five first-year students who responded to the NSSE’s survey of freshmen reported having difficulty learning course material and getting help with course work, findings that McCormick said should serve as a “wake-up call for colleges.” Another 26 percent of first-year students said they had difficulty learning course material, but that they did not have difficulty getting help.

The 21 percent of students who reported having difficulty with both had a lower average SAT score than students who reported not having difficulty getting help with their course work. Those students also spent one hour less on class preparation per week than their peers. About 43 percent of the first-year students who said they had difficulty learning course material and getting help with course work said they seriously considered leaving their institution.

First-generation, African-American and Hispanic or Latino students were more likely to have difficulty getting help with their course work than their peers.

“Part of this is that institutions have to teach students how to be successful, but they also have to teach them what our responsibilities are,” Charlie Nutt, executive director of the National Academic Advising Association, said. “We have to do that from day one, telling them that they are not alone and that here’s what an adviser does, here’s how to talk to a faculty member. For first-generation students, in particular, they may not have any clue how to approach these relationships, and they’re not going to unless we teach them. We can’t wait for them to find this out after they’ve failed their third math test.”