You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

You@CSU

Colorado State University

“Do parties or social situations ever make you uncomfortable?”

“How would you categorize your stress level?”

“How often would you say you feel overwhelming anger or irritability?”

These are some of the questions that greet students at Colorado State University when they log in to the university’s new online well-being portal, YOU@CSU. Created through a partnership with Grit Digital Health and officially launched this semester, YOU@CSU acts as a virtual counselor, asking students questions about their mental and physical well-being and directing them to the appropriate campus resources.

The platform is one of several digital tools -- from online portals to text messaging services and smartphone apps -- that colleges are using to provide wider access to mental health services as campus health centers struggle to meet the rising counseling demands of students. Use of what’s called telepsychology for mental health services is increasing, according a survey released earlier this year by the Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors. In the 2013-14 academic year, 6.6 percent of counseling centers reporting using telepsychology in some form. The following year, the figure was up to 9.1 percent.

“One of the things really concerning folks at university counseling centers is the growing demand for student counseling services,” Anne Hudgens, executive director of the Colorado State University Health Network, said. “It’s really hard to meet that demand and to sort through who has a critical issue and who is looking for help and support for more standard issues of stress and anxiety. We believe the help-seeking behavior of this generation is a positive thing, but we knew we had to find a way to get upstream.”

Dan Jones, chair of the Higher Education Mental Health Alliance and former president of the AUCCCD, said colleges have used distance counseling for years, though in the past those services connected students with licensed counselors over the phone. Jones said colleges that use hotlines, text message services and online behavioral therapy platforms aren’t aiming to replace face-to-face counseling, but to supplement it.

Early research, he said, suggests that telepsychology services can help students with issues like anxiety, but counselors are still determining the efficacy of the widening variety of digital tools in addressing other mental health issues. The Higher Education Mental Health Alliance, which includes the AUCCCD and other student affairs and mental health groups, is currently developing a new set of guidelines for colleges that use distance counseling and telepsychology services.

“The fact that there’s so many students using electronic equipment, these services are sort of a natural progression for counseling,” Jones said. “They’re a promising way to supplement counseling, and they’re proving effective for treating anxiety. We’re only just starting to learn whether they could help with more complicated problems.”

The Colorado State platform has two main functions. It acts as a personalized campus search engine, encouraging students to type in questions about mental health, physical fitness, campus life and career goals. A student wondering if there’s a way to meet people on campus with a similar background might be pointed to a cultural center or club. If a student’s searches indicate he or she is feeling suicidal, the website directs the student to call the campus counseling center and a suicide prevention hotline.

“The concept initially focused specifically on mental health and suicide prevention, but it grew into a more complete package,” Hudgens said. “It’s now about how you support students with a whole range of concerns. The goal is to reach students before their challenges have turned into a crisis.”

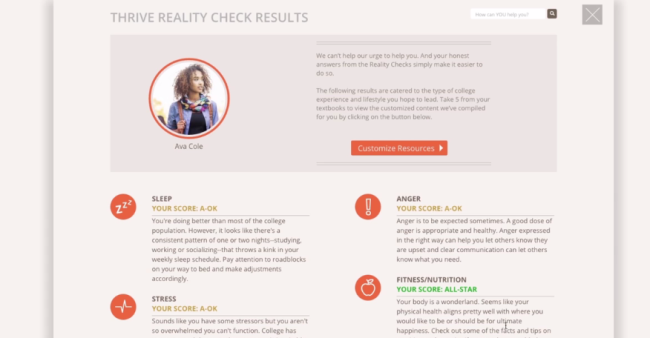

Students are also asked to fill out a series of questions -- what the platform calls “reality checks.” The assessments survey students on a variety of topics related to depression, suicide, body image, dietary habits and academic issues, among many other subjects. After completing the assessment, students are directed to a results page, where they are given next steps and recommendations on how to improve their mental and physical health. They are directed to specific campus resources if they are struggling in any particular area.

Last month, the fraternity Alpha Tau Omega announced that it was offering all of its members free access to a program called Unlimited Messaging Therapy through the app Talkspace. The app allows students to communicate with licensed therapists through text messages, photographs, audio and live video sessions. The fraternity is offering its members three months of the service for free.

“Fraternity chapters are ready-made communities that provide members a strong support system,” Wynn Smiley, ATO’s chief executive officer, said in an email. “At the same time, we want to provide the opportunity for any of our members who feel the need for some assistance the added benefit of professional counseling that is easily accessible. By effectively eliminating wait times, appointments and the anxiety of seeking mental health support, Talkspace is a perfect partner to help us shepherd a higher standard of mental wellness on campuses nationwide.“

Last week, the Steve Fund, an organization focused on improving the mental health of students of color, announced that it had received an $863,000 grant from the Knight Foundation to improve text messaging counseling services in “communities of color, while increasing data collection and research on the needs of this population.”

The Steve Fund already partners with a service called Crisis Text Line, which allows people struggling with anxiety, suicide, depression and other mental health concerns to talk, through text message, to a trained crisis counselor. Texting “Steve” to 741741 automatically connects students with the counselors. When people use that code, the counselor knows the person he or she is helping is likely a person of color. The grant announced last week will also be used to hire more minority counselors for the service.

Victor Schwartz, medical director for the Jed Foundation, a nonprofit organization that works to prevent suicide among college students, said digital tools -- both online assessment platforms and text message counseling -- can be a mixed bag. Many text messaging counseling services use qualified and licensed counselors, meaning if a student indicates he or she is suicidal, the person is trained to deal with the situation appropriately. That includes calling the police or other emergency services. As colleges increasingly turn to these services, Schwartz said, they should ensure they are staffed with the kinds of counselors that officials would want working in their campus health centers.

“Having access to virtual treatment is better than nothing,” Schwartz said, “but you have to make sure there’s some kind of process to very carefully vet who those people are on the other end of the line.”

Some services, including the online platform at Colorado State, allow students to remain anonymous, however, meaning even if the content on the site has been carefully vetted by psychologists, there is no way of knowing when students are in need of immediate help. “At the same time, this is not a problem specific to this kind of counseling,” Schwartz said. “There’s always been a struggle between knowing that students are more willing to open up if they aren’t worried about police knocking on their door, and knowing that if we allow that level of anonymity we may not be able to help them in time.”

There are some other concerns with online therapy outside of its inability to allow for crisis intervention. Last year, researchers at the University of York, in Britain, found that people who used computer-assisted cognitive behavioral therapy, experienced no improvement in dealing with their depression over a four-month period. The researchers wrote that such platforms were “likely to be an ineffective form of low-intensity treatment for depression and an inefficient use of finite health care resources,” and that “participants said they wanted a greater level of clinical support as an adjunct to therapy, and, in the absence of this support, they commonly disengaged with the computer programs.”

Schwartz compared most online therapy options to massive open online courses.

“There’s that same challenge, where the novelty wears off and participation drops off,” Schwartz said. “At the same time, it’s certainly not a bad idea to have this as an option for students. If a school has running wait lists, or there are students you know aren’t seeking help face-to-face, this could have a useful role. No one should get any clever ideas of this replacing counselors.”

The mental and emotional health of students has been of increasing concern to colleges in recent years, even as many institutions struggle to find the resources to better address those concerns. More than half of college students say they have experienced “overwhelming anxiety” in the last year, according to the American College Health Association, and 32 percent say they have felt so depressed “that it was difficult to function.”

Nearly 10 percent of incoming freshmen who responded to last year’s American Freshman Survey reported that they “frequently felt depressed.” It was the highest percentage of students reporting feeling that level of depression since 1988, and 3.4 percentage points higher than in 2009, when the survey found the rate of frequently depressed freshmen to be at its lowest.

But colleges are struggling to meet this demand, and the vast majority of students do not seek help for their mental health concerns. Access to services remains a serious concern for many counseling center directors, according to the AUCCCD survey. Many note that, lacking enough counselors to meet demand, they must use triage systems and put some students on waiting lists before they can receive treatment.

Generally, smaller colleges reported shorter times of years that they had waiting lists for treatment. At colleges with enrollments of 1,501 to 2,500, directors reported an average of eight weeks a year in which waiting lists were used. At colleges with enrollments of 25,001 to 30,000, waiting lists were used an average of 23 weeks a year. At colleges with enrollments greater than 15,000, the average number of students on waiting lists exceeded 50, and it was as high as 70 for institutions with enrollments of 30,001 to 35,000.

As such, many colleges have tried widening access to mental health services for students in distress. In recent months, several colleges have announced that they will expand the hours and locations at which counselors can be sought out.

Earlier this year, the University of Iowa announced that it would hire eight new counselors to meet rising demand for more mental health services among its students. Currently the university has 12 counselors on staff. Rather than setting up new offices in the university’s counseling center, however, some of the new counselors are being embedded in various buildings around campus. In April, Pennsylvania State’s senior class raised money to create an endowment that would embed a counselor in a residence hall.

After complaints from students, Skidmore College hired an additional counselor and contracted with an outside firm to offer a 24-hour telephone hotline. Last year, following the suicide of a New Jersey woman who attended the University of Pennsylvania, the New Jersey State Senate passed a new law requiring that mental health professionals be available around the clock to assist the state’s college students. In January, Willamette University in Oregon partnered with ProtoCall, a 24-hour mental health hotline, to provide around-the-clock support to students. Amherst College launched a similar hotline about a year ago.

The online and texting tools now being used at some colleges are extension of that same desire to make mental health services more accessible. Nathaan Demers, a licensed clinical psychologist and director of clinical programs at Grit Digital Health, said distance counseling and telepsychology services are not intended to replace in-person counseling. Instead, he said, the goal is to reach students who wouldn’t otherwise receive any counseling.

“As a college counselor, I loved working with students, but who I worried about the most were students who didn’t come into my office,” Demers said. “We have an ethical responsibility to connect with people who are not knocking on our door. Digital technology is the first place where millennials are going to look for help.”