You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

With up to 600 colleges working to create competency-based education programs, a new report examines the business model for this emerging approach to higher education, finding significant savings possibilities for colleges and students alike.

According to the report, four institutions that were early adopters spent an average of 50 percent less per student on education-related activities in competency-based degree tracks compared to their traditional programs.

The rpkGROUP, a consulting firm that advises colleges on financial matters, conducted the analysis. The Lumina Foundation funded the report.

Some of the cost savings the report identified can be passed to students in the form of lower tuition rates. And the focus on mastery in competency-based education can give students a chance to move at their own pace, the report said, potentially earning a degree faster than they would otherwise.

However, achieving a 50 percent efficiency gain while preserving academic quality and fundamentally altering the role of faculty members is far from easy, according to the report and to experts who have helped create new competency-based programs.

“This is not going to be a quick revenue source,” said Deb Bushway, a higher education consultant who has previously worked for Capella University and the University of Wisconsin Extension. “People have to be in it for the long haul.”

One challenge, the report said, is that programs will need to attract substantial numbers of students to achieve economies of scale. That has not happened in most cases, at least not yet, as the typical competency-based education program remains fairly small.

An exception to this rule is Western Governors University. The nonprofit WGU currently enrolls more than 70,000 students in its fully online, competency-based degree programs. Tuition at the university is a flat rate of about $3,000 per six-month term (somewhat more in M.B.A. and nursing programs).

The four institutions included in the new report -- Wisconsin Extension, the Kentucky Community & Technical College System, Brandman University and Walden University -- are, while newer to competency-based education than WGU, still pioneers in the field.

For example, the three universities offer a new form, dubbed direct assessment, which is completely untethered from the credit-hour standard.

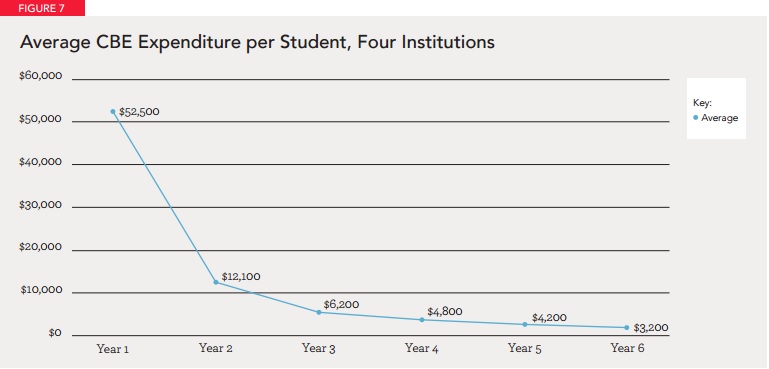

To create their competency-based programs, the four institutions in the report spent an average of $4.2 million during the first year. About one-quarter of that spending went toward curricular development, with the rest paying for staffing, technology and other infrastructure expenses.

Start-up costs grew during the first three years -- to a range of $6.3 million to $11 million -- after additional spending on technology and curricula.

The four institutions project an average annual cost of $3,200 per student in education-related spending once their programs mature. By the fifth year of operation, three of the four institutions expect the programs to be able to cover their annual operating costs. But getting there requires aggressive enrollment growth, the report said, of 150 percent annually for five years.

“The break-even point -- when annual per-student revenues exceed expenditures -- occurs in the fifth year of operation, when enrollment averages just under 6,000 students,” according to the research.

That timeline is consistent with most new businesses. But an enrollment of 6,000 students is hardly a boutique program -- a term that currently describes most competency-based degree offerings.

The report said a reason colleges will need a relatively substantial student population to make competency-based education sustainable is the low tuition rates most now charge.

“Current competency-based education programs have quickly settled around a price range of $5,000 to $6,000 in annual tuition. This price range reflects historical pricing set by industry leader Western Governors University, combined with a desire to maximize access to competency-based education programs,” the report said. “In some cases, this price range was established before a full business model was developed and before the revenue streams and expenditure structures behind each competency-based education program were fully understood.”

As a result, pricing may have to be higher for smaller programs, said Rick Staisloff, rpkGROUP’s principal and a co-author of the report.

“Be careful about locking in too early to that price point,” he said.

Faculty Role

Much of the savings in competency-based education, as well as much of the controversy, center on the new roles and responsibilities it creates for faculty and staff members.

Not all competency-based programs require such a reorganization, the report said. But typically, some faculty members serve as the primary architects of course content, said the report, either creating it or turning existing content into competencies and developing related learning assessments. Faculty members who don’t work on the content then have more time to work with students.

“This unbundling of faculty roles allows them to provide more students with advice and assistance as they tackle different learning experiences,” the report said.

Other new roles in competency-based programs that the report identifies include enrollment coaches, academic success coaches, mentoring faculty and learning outcomes assessors.

When combined with technology, such as automated online course material and adaptive, personalized learning software, the unbundled faculty role can lead to much higher student-to-faculty ratios than in traditional programs, the report said, without sacrificing academic quality.

The average ratio of students to so-called mentoring faculty, or subject-matter experts, at the four institutions in the report is expected to be about 200 to one. Those ratios range from nine to 18 students per faculty member in the institutions' traditional instructional formats.

In addition, some of the new student support roles in competency-based education tend to come with lower salaries than what colleges pay faculty members. For example, average salaries ranged from $38,000 to $62,000 for academic success coaches at the four institutions, the report found.

Several academics have criticized the push for efficiency in competency-based programs, arguing that this approach reduces the role of teaching professors while putting students’ mastery of skills over their knowledge of a subject.

“Budget versions of education, like surgery or car repairs, are no bargain,” wrote Amy Slaton, a professor of history at Drexel University, in a 2013 essay. “In such outcomes-focused college curriculums, stripped of ‘unnecessary’ instruction, open-ended, liberal learning easily is deemed wasteful.”

Advocates for competency-based education disagree, saying this model can offer more academic rigor than a traditional program, in addition to offering flexibility and affordability to students.

“What students need to know, understand and be able to do to earn credentials is clearly articulated and students can progress rapidly through competencies they have previously mastered, which could shorten the time to degree,” the report said. “Students also are provided additional time for mastering application of difficult concepts.”

Even so, concern about the faculty role in competency-based education poses a threat to this approach, and not just a theoretical one.

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Inspector General has issued several critical audit reports that said the department and accreditors did not adequately scrutinize new competency-based programs.

Specifically, the reports questioned whether those programs included “regular and substantive interaction” between faculty members and students. And Western Governors is awaiting the results of a multiyear audit by the inspector general that focuses on similar issues. The results could have a big impact on WGU and competency-based education on the whole.

Staisloff advised colleges that are considering a new competency-based program to study the regular-and-substantive issue.

“Get smarter about it and get ready,” he said.