You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

As tuition prices and student loan debt weigh on the minds of students, they’re paying more attention to the payoff from specific majors or degree programs. But the College Scorecard, the consumer tool the U.S. Department of Education introduced last year, reports only outcomes for a particular college overall and for those students who receive federal financial aid.

That’s because of a ban enacted by the U.S. Congress on a federal student-level data system. So students are left with a broad view of institutions' results where data is available.

“When the data you collect and use focuses on schools instead of students, then you can't answer some pretty basic questions about the value of higher education,” said Tom Allison, policy and research director for the Young Invincibles, a think tank focused on young people.

When the group called recently for the federal ban's repeal, it came amid a changing political landscape. Multiple higher education associations have come around on the idea, and a number of prominent conservative Republicans have expressed interest in more transparency on student results in higher education.

In the absence of quick movement to repeal the prohibition, however, states and universities are moving forward with their own workarounds to the ban to track student outcomes.

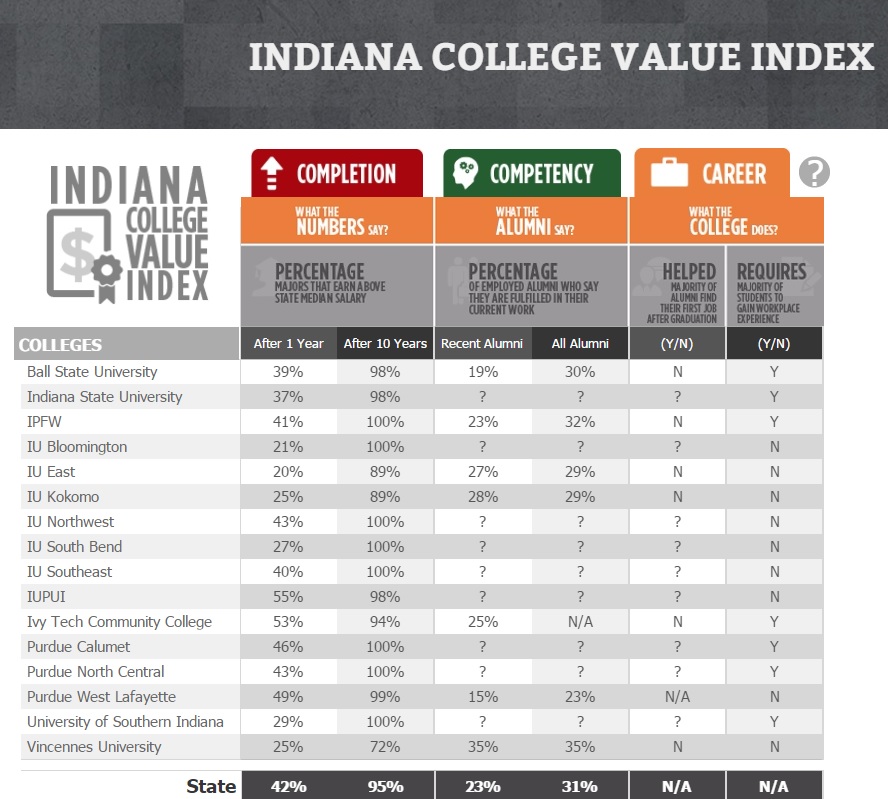

In Indiana, the Commission on Higher Education last month launched the Indiana College Value Index. The state got help from USA Funds and Gallup to release a set of metrics that takes into account both quantitative and qualitative measures.

The index doesn't rank Indiana's colleges and universities. Instead, it aims to provide students and families with information on completion, postgraduation salary and satisfaction of university graduates.

Teresa Lubbers, who leads the commission, said Indiana already has explored performance-based funding in public institutions. The rising cost of college in recent years has contributed to discussions about the value of higher education, she said.

“People are asking, ‘Are you funding things that matter to the individual and to the state?’” Lubbers said. “In order to [answer] that, you have to have data, you have to have metrics you’re aiming for and you have to publish them.”

Farther south, the University of Texas System last month announced a partnership with the U.S. Census Bureau to track the postgraduation outcomes of alumni who have moved across the country. Development of that program began in 2012, after the system's Board of Regents received recommendations from a student debt task force.

Stephanie Huie, vice chancellor for the system's Office of Strategic Initiatives, said UT currently tracks postgraduation outcomes for students who reside in Texas by sharing information with the state workforce commission. But the system can’t calculate employment rates or wage data for graduates who move outside of the state. And the College Scorecard, which collects data on students who have received financial aid, reflects only 43 percent of the system's graduate population, she said.

“That isn’t the fault of the Department of Education,” she said. “They’re doing the best they can. They don’t have all the data they would like to have access to.”

Huie said the partnership with the Census Bureau, which is a pilot project for the agency, could demonstrate the value of matching student-level data with information on earnings for all UT alumni, no matter what state they live in. The data would help the system better inform students at its campuses while also finding programs that could be improved and providing more resources in the state appropriations process.

Republicans and the Higher Education Lobby

In the last two years, the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities and the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators have come out in favor of some kind of federal student-level data system.

House Speaker Paul Ryan of Wisconsin is among a number of Republican leaders who now support legislation to add transparency in higher education, along with prominent Democrats like Senator Patty Murray of Washington. But the House education committee itself -- where any legislation on a repeal would originate -- remains a major obstacle to hopes for movement on the issue. Only one Republican committee member, Representative Joe Heck of Nevada, has come out in favor of removing the ban. And Heck is running for Harry Reid’s Senate seat, so he will either be in the upper chamber or out of Congress entirely next year.

The likely next chair of the committee, North Carolina Republican Virginia Foxx, remains steadfast in her opposition to a federal student-level data system. Foxx, who sponsored the ban in 2008, said the privacy concerns that motivated the ban remain as significant as ever.

“When Congress prohibited the creation of a federal database to collect personally identifiable information on individual college students, it was respecting the deep concerns that Americans have about government intrusion into their private lives,” she said in a written statement. “Today, those concerns are as relevant as ever. It’s apparent there is also a need to provide more accountability in the higher education system. As we continue to discuss reauthorization of the Higher Education Act, we will work to protect the privacy of students and ensure strong accountability.”

That position is supported by the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities, which represents more than 1,000 private nonprofit institutions and is the last serious holdout among major higher education associations on a student unit record ban.

Amy Laitinen, director for higher education at New America, wrote in a 2014 report that NAICU has exercised an outsize influence in blocking a possible repeal.

“They’ve historically been the problem and they continue to be the problem,” she said.

Laitinen said other higher education associations are no longer on the sidelines on the issue because they’ve seen that it is in their interest to make sure data featured in tools like the College Scorecard are accurate. While she sees reason for optimism in the new interest of Republican leadership in pushing for transparency, she said NAICU still holds sway among GOP committee members.

“The committee really sees the associations as their constituents,” she said. “They should look at the students as their constituents. It’s classic regulatory capture.”

Sarah Flanagan, NAICU's vice president for government relations and policy development, said it is misleading to suggest that the association is the only source of motivated opposition to a student-level data system.

“There is a federal ban because members of Congress advocated for a federal ban,” Flanagan said. “If Congress changed its mind, the ban would be removed.”

She said proponents of a repeal still have yet to seriously address the privacy concerns that originally motivated the ban. Laitinen, for her part, said the data in question are already being collected at the state level or by federal agencies and are just not being shared in a useful manner.

The Association of Big Ten Students was one of several student organizations that contributed feedback to the Young Invincibles' data reform agenda. But the group has been active on the repeal of the student unit record ban going back several years, meeting with members and congressional staffers each spring.

“It's something that is on people's radar,” said William Dammann, a University of Minnesota Twin Cities senior who serves as the association’s legislative director. “It's interesting, because when you talk to people about the idea behind [the repeal], they say, ‘Well, I don't get it. Why aren’t we getting this information? It doesn't make sense.’”

Mark Schneider, vice president and institute fellow at the American Institutes for Research, said advocates of a repeal would have more success politically if they dropped the term “student unit record.”

“The problem is the term is toxic,” he said. “You use any of those three words and people on the Hill, many staffers and representatives, just go crazy.”

Schneider said advocates should talk about student-level data systems instead, of which there are multiple examples. He pointed to the efforts at the UT system and in other states -- he helps lead a company working on data systems in Colorado and Tennessee -- as evidence of momentum for making student data more widely available.

But those programs, even when they account for all students, provide only outcomes on students from a particular state. And the College Scorecard, which is based on federal aid data, only accounts for students who have received aid.

“Right now we’re just doing all kinds of workarounds because of the fact that many student-level data systems exist,” Schneider said. “They’re all workarounds, right? And that’s the problem.”