You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Bard College spent $18 million on 380 acres of land housing a historic mansion this year but now faces financial concerns amid a ratings agency downgrade.

Bard College

A ratings agency's downgrade of Bard College has raised anew longstanding questions about the small private college's business strategies, with the spotlight falling on cash concerns at an institution known for prioritizing idealism and expansion over conservative financial models and endowment building.

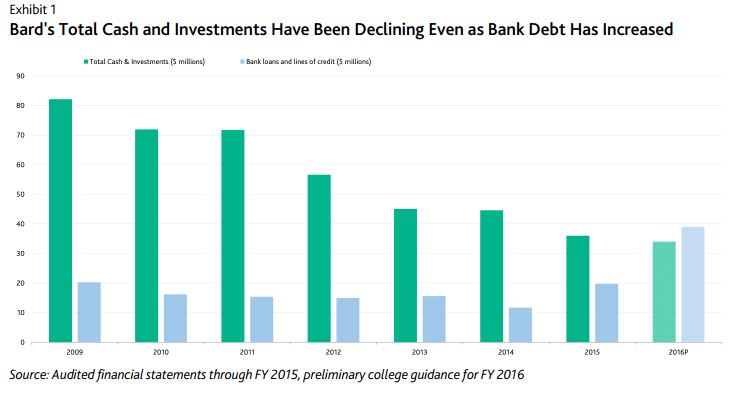

Moody’s Investors Service issued an opinion Aug. 16 downgrading the credit at the small liberal arts college about 100 miles north of New York City, edging it farther into junk territory. The ratings agency pointed to declining total cash, an increasing dependence on lines of credit and Bard's heavy borrowing from its endowment. In short, the institution’s available financial assets have dropped as it has run up higher debt, increasing the possibility of a cash crunch. That in turn puts more pressure on the college to collect donations to fund itself.

“The ongoing depletion of liquidity and increased exposure to bank agreements heightens the prospects for a liquidity crisis in the absence of extraordinary donor support,” Moody’s said in its credit opinion. “With a cash flow from operations insufficient to cover debt service, prospects for a material increase in liquidity apart from collecting pledges receivable or benefiting from additional gifts remain slim.”

Moody’s analyst Edie Behr put it another way in an interview.

“The college is dependent on its endowment and cash flow from borrowing to pay its debt,” she said. “They are not making enough through their core operations to pay their debt service. That’s fairly uncommon.”

Bard has faced ratings downgrades before, with college leaders retorting that they follow a different financial model from most in higher education. Bard’s outspoken longtime president, Leon Botstein (pictured below), has in the past fiercely defended this alternative philosophy, asserting that institutions of higher learning should not function like banks hoarding wealth but should instead spend their money on projects and education.

The college's leaders are reiterating that argument today. But they’re doing so after many of Bard’s financial indicators have deteriorated over the last several years. Now it remains to be seen whether the institution can continue to deal with its high debt levels -- or whether its finances are a house of cards that will eventually collapse.

Bard continues to raise money from donors, according to Taun N. Toay, vice president for strategic initiatives and chief of staff. It recorded $36 million in new pledges last year, he said in an email.

“While we acknowledge the weight some afford Moody's as it relates to bond buyers, they are not measuring our ability to fulfill our mission as a college and are also comparing us to colleges and universities that appear to focus more on their already large endowments than on innovation and education,” Toay said. “We are a nonprofit private institution operating in the public interest, and will continue [to] invest in programming and maintaining our world-class campus and network.”

Toay went on to say that Bard is putting strategies in place to address Moody’s concern about liquidity, although he did not share details on those strategies. He also said Bard has operated on its current model for more than 40 years without ever missing a bond payment.

In that light, this month’s downgrade looks almost like business as usual for Bard. A Moody’s downgrade at the end of 2013 sparked worries when the investors service dropped Bard three pegs from Baa1 to Ba1, moving it from investment grade into the top of junk territory.

At the time, Moody’s wrote that Bard had only had enough cash on hand in October to fund two weeks of operations. Moody’s estimated Bard had drawn 43 percent of the previous year’s budget from donations and that the institution’s debt, which stood at $185 million, was roughly on par with its operating budget.

Fast-forward to this month, and some financial indicators at the college appear to have improved. Bard has trimmed its reliance on philanthropy for operating revenue by six points -- it relied on gift revenue for 37 percent of its total operating revenue in the 2015 fiscal year, according to Moody’s. Philanthropic support is strong and is a key supporting factor in Bard’s current credit rating, Moody’s wrote. Bard’s cash on hand stood at 22 days as of June 30, up from the two weeks in 2013.

Those indicators aren’t without caveats, however. The 22 days’ cash on hand was down from 30 in 2015 -- and cash on hand can increase as institutions draw on their lines of credit, obscuring larger financial issues. Meanwhile, the reliance on gifts for 37 percent of total operating revenue was still “uncommonly high exposure,” according to Moody’s.

The agency’s credit opinion this month dropped Bard’s rating from Ba3 to B1, moving its debt farther into junk territory and signaling a high credit risk. Moody’s also assigned a negative outlook, citing a “profoundly vulnerable liquidity profile” at Bard.

The negative outlook signals downward pressure on the college’s bond rating. Credit rating downgrades can have significant consequences for an institution by making it more expensive to borrow money.

Moody’s listed Bard’s total financial resources at $191 million. But $111 million is in an externally held trust supporting just a small portion of the college’s operations. Borrowing from the endowment has also accelerated over time. The borrowing totaled $96 million as of the 2015 fiscal year.

At the same time, debt has grown faster than revenue. Bard’s operating revenue grew 1.6 percent year over year, to $190.3 million in 2016. It was outpaced by total debt, which grew 17 percent to $203 million.

One noteworthy driver of the debt increase was a $4 million settlement announced by the U.S. Department of Justice in March. Bard agreed to pay the money to resolve allegations it received funds under the federal Teacher Quality Partnership Grant Program but had not complied with the grant conditions, and to resolve allegations that it awarded, disbursed and received Title IV student loan funds at campus locations before those locations were accredited or before providing notice of the locations to the Department of Education.

The settlement came after a whistle-blower complaint filed by two former students at Bard’s master of arts in teaching program at Paramount Bard Academy, in Delano, Calif. Bard acknowledged no wrongdoing. It pulled out of the charter school in 2013.

A larger driver of the debt was a purchase of the 380-acre Montgomery Place estate in January 2016. Bard bought the estate, which is adjacent to its Annandale-on-Hudson campus and includes a historic mansion, farm and 20-odd smaller buildings, for a reported $18 million. That purchase price includes $1 million for antiquities on the site. Bard used a $13 million seller-financed mortgage to help pay for the acquisition.

The Department of Justice settlement was small in terms of Bard’s total operations, Toay said in his email. He called the Montgomery Place purchase a strategic investment that would be neutral in terms of operating costs.

“The cost of that purchase is far outweighed by the value of the property both in terms of real estate and of programming potential,” Toay wrote. “In setting the stage for Bard’s long-term future, acquiring 380 [contiguous] acres was a wise investment and speaks to the underlying strength of the college.”

Monetizing assets like land can be tricky, however.

“When you talk about buying land, if it’s going to provide the opportunity for growth, you need additional capital to turn that into an asset that’s actually generating revenue,” said Bob Shea, a senior fellow for finance and campus management at the National Association of College and University Business Officers. “Just buying the land and holding onto the land is an expense. Turning it into dormitories or something that’s going to have a revenue stream, that makes sense as part of a strategic plan.”

Bard said when it acquired the land that it would begin creating a master plan. It has received a $100,000 foundation grant for repairs and renovations of a greenhouse on the land.

One more notable 2016 expense concerned the American Symphony Orchestra, where Botstein is the music director. Bard has an agreement with the orchestra to cover any of its unfunded expenses, although college leaders told Moody’s some trustees guarantee those expenses. The agreement led to Bard absorbing $1.5 million from the symphony’s operating deficit in the 2016 fiscal year, according to the ratings agency.

Bard has made a number of other investments in programs in recent years. For example, it acquired the Longy School of Music in Cambridge, Mass., in April 2012. That deal came shortly after it acquired a European institution in November 2011 in order to create Bard College Berlin.

After Moody’s dropped Bard’s investment rating from investment grade to noninvestment grade in 2013, Botstein called financial questions a distraction.

“When you have bond raters peering over your life’s work, it’s like hanging a painting in front of semi-blind people,” he said at the time.

Faculty members see benefits from Botstein’s strategy.

“By all accounts, Bard has been an extremely vibrant intellectual community over Leon’s tenure,” said John Halle, director of studies in music theory and practice at the Bard College Conservatory of Music, in an email. The conservatory was founded in 2005.

There is an argument to be made that Botstein, who took over at Bard in 1975, can keep finding donor support for his college. He’s proven himself to be an able fund-raiser for the institution, bringing in high-profile donors like George Soros, Leon Levy and Richard Fisher. He has wooed donors without ties to the college, an important skill for the president of a liberal arts institution that, with just 2,800 full-time equivalent students and a reputation for idealistic scholarship, does not have the largest pool of wealthy alumni to tap.

Fund-raising, however, can be an imperfect science. It’s generally regarded as a difficult way to reliably fund operations, even though practically every private -- and many public -- institution is banking on building endowments for a sustainable future.

“That really is the crux of the credit issue,” said Behr, the Moody’s analyst. “This college is very unique in that they have tens of millions of dollars of pledges, and there is no certainty with regard to when those gifts will be received. And in the interim, the college operates hand-to-mouth, drawing on these lines of credit for cash flow.”

Fund-raising is also very much driven by personality. Moody’s noted that Botstein, who is nearly 70, has said he intends to remain at Bard for another decade, but it also noted he tightly controls Bard’s management. At the same time, Moody’s said Bard’s board is becoming more involved in financial planning and liquidity management.

Botstein continues to be outspoken about a number of issues. This month he wrote an editorial calling on Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton to forgive student loan debt and create a new loan program if she is elected. One line in the piece said, “We must underscore the fact that universities are not businesses.”

It’s unclear whether Bard operates differently enough from other institutions that it cannot serve as an early indicator of spreading financial troubles. The college’s strategy may be unique enough that it is in its own class. Moody’s only assigned nine institutions in its not-for-profit higher education arena a rating at or below B1 -- the rating just assigned to Bard.

Still, Bard’s troubles do fit into a broader narrative about head winds many institutions are facing. Colleges and universities of different sizes are running into demographic, cost, technological and economic challenges, said David Strauss, a principal at Art & Science Group, a Baltimore-based consulting strategy firm.

“It’s a real competition, and there are winners and losers,” he said. “Have they carved out a substantive appeal that is compelling enough to draw kids to come and to pay enough of the freight to support the place? So far, the answer you’re giving is ‘Not yet.’ And that’s the answer for a lot of colleges and universities around the country these days.”

Bard’s discount rate in the 2016 fiscal year was in line with the national average -- 48 percent, according to Moody’s. Net tuition revenue per student was $26,000.

So the open question remains whether Bard can find a way to keep its balance sheet in good enough shape to convince bankers and donors to support its ideals.

“They may very well march to the beat of a different drummer,” said Rick Hesel, another principal at Art & Science. “But if you run out of cash, the drummer stops beating.”