You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

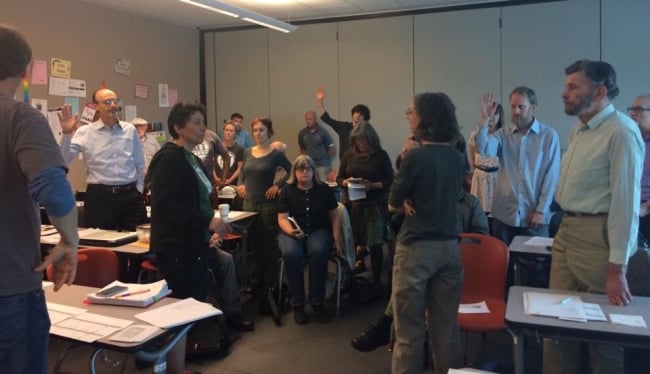

CCSF union members voting to strike next week

AFT 2121

City College of San Francisco’s long-running accreditation crisis has gotten expensive for taxpayers in the city and state, with California's government ponying up $100 million in extra funding for the college over the last three years.

The state in 2012 passed a law to create the new stabilization funding stream, mostly to protect City College from enrollment declines due to its uncertain accreditation status, which understandably appears to have scared off large numbers of students.

“This college, had we not received the stability funding, would have been decimated,” said Susan Lamb, City College’s interim chancellor. “It would have destroyed the college and the community, in so many ways.”

Enrollment is down 35 percent since 2012, when the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges sanctioned City College for a wide range of financial and administrative problems. It currently enrolls the equivalent of roughly 21,000 full-time students, which is down from about 33,000 when the accreditation woes began.

San Francisco’s residents also have helped the college ride out the budget crunch of losing so many students (and their tuition dollars and state subsidies). The city’s voters in 2012 passed a new parcel tax, which has generated about $15 million in annual funding for the college.

Likewise, City College also has benefited from Proposition 30, the bundle of new sales and income taxes California voters approved in 2012. The college’s budget for this year includes $25.5 million in revenue from those taxes.

The three new streams of money, which add up to roughly $75 million in funding this year, have helped City College come back from the brink of bankruptcy. But the funding is due to expire soon, with some money drying up next year and all three funds gone by 2020. And the college is wrestling with how much to shrink -- meaning cuts to the number of courses it offers and the numbers of instructors who teach those courses -- amid losing more than a third of its students.

That tense discussion is occurring as the college’s leaders and its primary faculty union are at loggerheads over a new employment contract. And the union’s members voted overwhelmingly to stage a one-day strike next week.

Lamb said the college is trying to rebuild its enrollment, through advertising and work with city partners, including the local K-12 district. While she’s confident the college will restore its numbers, that process will take years. And some cuts loom in the meantime, she said, particularly as the temporary funding streams dry up.

“We are actively reducing the schedule,” said Lamb, who was brought in last year and is City College’s fourth leader since the accreditation crisis began. “It’s a tough time. It’s a defining moment in the college’s history.”

Faculty union leaders aren’t buying the administration’s argument that reductions are needed. The local chapter of the American Federation of Teachers, a national faculty union, said the college’s leaders now are doing the work of the “rogue” accreditor, the ACCJC.

Tim Killikelly, the chapter’s president and a political science professor at City College, said in a written statement that faculty pay levels are more than 3 percent lower than they were in 2007. He also criticized still-emerging plans by the college’s leaders to shrink City College by 26 percent, particularly given that the college now has substantial cash reserves. City College has $36 million in unrestricted reserves, according to the Fiscal Crisis and Management Team, a state agency tasked with assisting public colleges and schools.

“San Francisco is not 26 percent smaller than it was in 2007; in fact it has grown,” Killikelly said.

As a result, Killikelly said, 92 percent of the union’s members made the tough call to strike next week.

“We understand strikes have consequences for everyone -- it has consequences for faculty, it has consequences for students, it has consequences for the city,” he said. “We understand that, but the situation has become intolerable over the past several years.”

Crisis Averted, for Now

How to use financial reserves wasn’t a problem for City College in 2012, when the commission slapped on sanctions.

Shortly after the accreditor’s action, a team of state auditors criticized the college for having flimsy finances. City College only had three days’ worth of cash reserves on hand and was facing possible bankruptcy with a projected budget deficit of $25 million and growing.

“City College of San Francisco has not developed a plan to fund significant liabilities and obligations such as retiree health benefits, adequate reserves and workers’ compensation costs,” concluded the state fiscal crisis team in a 2012 report. “Further, it has been subsidizing categorical programs with unrestricted general fund monies regardless of the effect on the general fund, and has provided salary increases and generous benefits with no discernible means to pay for them.”

That situation changed dramatically, although temporarily, when the state and city stepped up with infusions of new money most community college leaders could never dream of receiving.

Two years ago the state contributed $28 million in additional stability funding, a formula calculated to cover the full amount of state funding based on enrollment levels from before the sanctions. The next year City College got $39 million more in stability funding from the state, with $33 million slated for this year’s budget. That adds up to $100 million over three years for City College, which has an annual budget of about $200 million.

City College released a budget presentation showing the stability funding has been almost 20 percent of the college’s total revenue in recent years.

“It’s a lot of money,” said Fred Glass, communications director for the California Federation of Teachers, a union representing many faculty members at the California colleges. But the funding was necessary, he said, thanks to the accreditor’s actions. “Serious damage was done to City College’s enrollment.”

The college is slated to receive an estimated $25 million in stability funding from the state next year. After that, the fund runs dry unless it’s renewed by California’s Legislature.

Lamb said the college is interested in pursuing new state funding for “restorative growth.” City College also is mulling a proposal to extend the parcel tax.

Meanwhile, the college has until the fall to prove it is in full compliance with its accreditor. The ACCJC is scheduled to send a team to the college this fall to determine whether it has fixed problems the accreditor identified and cited in the 2012 decision to threaten yanking City College’s accreditation.

“We have had this shadow over us regarding accreditation,” Lamb said. “We are working hard to meet the standards.”

The college has made financial progress as well, thanks to the infusion of funding. The $36 million in cash reserves is a big improvement from City College's flirt with bankruptcy a few years ago. The college and its governing board also recently met benchmarks the state’s fiscal crisis team set for adopting prudent fiscal policies and controls.

“The board is managing the pressure to compromise prudent fiscal principles and is not ignoring the messages in the multiyear financial projections in response to the faculty’s compensation demands,” the state agency wrote earlier this month.

Will Students Return?

The enrollment crunch at City College remains a serious problem. And the college faces challenges in reducing the size and cost of its class schedules, according to the fiscal crisis team, as it seeks to adjust to much smaller enrollments.

Leaders at the college also are contending with the possibility of an economic downturn, which always looms in California’s boom-and-bust cycle, as well as coping with demographic shifts in hyperexpensive San Francisco.

“The city is becoming increasingly unaffordable for many of the demographic groups that have traditionally been the majority of the CCSF’s student population,” the state fiscal crisis team said. “Additionally, unlike the traditional characteristics of most CCSF students, the demographics of those moving into the city tend to be highly educated and employed in higher-paying and time-intensive jobs.”

The financial pressures will get urgent quickly, the fiscal crisis team said, if City College is unable to secure extensions to its stability funding or to the parcel tax, which expires in 2020. Proposition 30 revenue also begins to peter out next year. (Meanwhile, a member of the city's Board of Supervisors has introduced a "free" community college proposal for the city, which would cost an estimated $13 million per year.)

“Efforts to extend the parcel tax may be challenged by the potential negative effects of either a threatened faculty strike or a board-approved salary increase that is seen as excessive by the voters,” the fiscal crisis team said.

Even so, the college appears likely to survive its multiyear accreditation woes. The same might not apply to the accreditor, the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges, which has faced a wide range of criticism for how it handled the City College crisis, including from the federal government.

California’s community college system has been working on making a change to its accreditor. The system’s governing board in March voted to get rid of the commission. But that would take several years, so the system also is mulling possible changes to the accreditor’s structure and leadership, rather than fully replacing it.

Glass, of the California Federation of Teachers, blamed the commission for City College’s plunging enrollment and subsequent need for more state funding.

However, Barbara Beno, the commission’s president, said City College’s financial problems preceded the sanction by the commission.

“The college’s precarious financial position was also documented by independent parties, including the college’s own external auditor and the state’s Fiscal Crisis Management Assistance Team,” she said via email.