You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

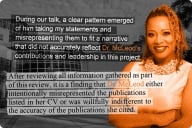

Christle Nwora, a University of Texas senior, and others from the university, after arguments at Supreme Court

U of Texas

The U.S. Supreme Court on Wednesday heard arguments in a case that, if one side gets its way, could limit or even ban the consideration of race and ethnicity in admissions decisions.

With the stakes high, many observers have been hoping for some indication of how the justices will rule in the case. But the strongest statements came from justices who have fairly consistent records on issues of race and education. Justice Antonin Scalia didn't leave doubt about his disdain for affirmative action, and some of his comments angered advocates for minority students. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, by contrast, didn't leave much doubt of her disdain for those who minimize the role of race in American society.

But the votes of those two justices (and others who spoke) haven't been much in doubt.

Justice Elena Kagan has recused herself on the case because she worked on it while in the Justice Department before joining the Supreme Court. Her recusal leaves only three justices who have generally been open to the consideration of race in education. Nothing said by Justice Sotomayor or the two others -- Justice Stephen G. Breyer and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg -- suggested that they have changed their view.

The other five have generally been dubious of the consideration of race. Justice Clarence Thomas, as is his habit, did not ask questions, but if he didn't vote against affirmative action, most court observers would be stunned. Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, whom supporters of affirmative action hope to sway despite his past skepticism on the consideration of race by schools and colleges, didn't really tip his hand. At one point, he wondered if the case should be remanded to a district court to gather more evidence, but as his questions continued, he seemed to doubt that anything new would come out of such a move.

The case attracting all the attention is Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin. This is actually a return to the court for the case. Ruling 7 to 1, the court in 2013 found that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit had erred in not applying “strict scrutiny” to the policies of UT Austin. The case is back at the Supreme Court because the original plaintiff and her lawyers maintain that lower courts did not adequately follow the Supreme Court’s directions in considering the case after the 2013 ruling.

The plaintiff in the case is Abigail Fisher, a white woman rejected for admission by the university who said her rights were violated by UT Austin's consideration of race and ethnicity in admissions decisions. Fisher's lawyers argued that the University of Texas need not consider race because it has found another way to assure diversity in the student body. That is the “10 percent plan,” under which those in the top 10 percent of students at Texas high schools are assured admission to the public college or university of their choice. The university maintains that it does not get enough diversity through the 10 percent plan, and should have the right to consider race.

Slower Tracks?

The most discussed line of questioning came from Justice Scalia, who argued that affirmative action may hurt black students. His language had many on social media calling him a racist.

"There are those who contend that it does not benefit African-Americans to get them into the University of Texas, where they do not do well, as opposed to having them go to a less advanced school, a slower track school where they do well. One of the briefs pointed out that most of the black scientists in this country don't come from schools like the University of Texas," he said.

Black scientists, he said, "come from lesser schools where they do not feel that they're being pushed ahead in classes that are too fast for them," he added. "I'm just not impressed by the fact that the University of Texas may have fewer [black students]," Scalia added. "Maybe it ought to have fewer. And maybe … when you take more, the number of blacks, really competent blacks admitted to lesser schools, turns out to be less. And I don't think it stands to reason that it's a good thing for the University of Texas to admit as many blacks as possible."

While Scalia's words angered many who read about them, he was actually making an "overmatching" argument that has been used by many critics of affirmative action (and rejected by many supporters of affirmative action).

The argument is viewed by many as an attempt to suggest that one can be against the consideration of race in admissions and at the same time concerned about minority students. Defenders of affirmative action, of course, note that while there are of course many minority students (not to mention white students) who may not thrive at competitive colleges, many others do -- and very much want that chance.

Via email, Raynard S. Kington, the president of Grinnell College, who has studied the educational trajectories of black scientists, said that "the suggestion that African-American students are not smart enough to go to academically challenging schools such as the University of Texas at Austin is just sort of unbelievable and offensive." He added that there is great heterogeneity among students of all races. "There are African-American students for whom the local community college might be better than the University of Texas, Austin, but guess what? There also are African-American students for whom Harvard is better than the University of Texas, and the same can be said for white students."

Although Scalia's questions attracted the most attention, other justices' comments may have focused more on issues that could be crucial to the outcome. The justices who in the past have been supportive of affirmative action had questions about whether the plaintiff's lawyers would be challenging the consideration of race if Texas did not have the 10 percent plan. They seemed to be suggesting that a defeat for Texas would limit admissions options and diversity throughout American higher education, not just at the University of Texas.

And Chief Justice John Roberts raised questions about the "critical mass" argument used by many supporters of affirmative action (including the University of Texas), who say that it is important for colleges not only to have some minority students, but to have enough that they are represented in a broad range of classes. Justice Roberts seemed dubious, asking, "What unique perspective does a minority student bring to a physics class?"

An unofficial transcript of the arguments, by the Alderson Reporting Company, may be found here.