You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

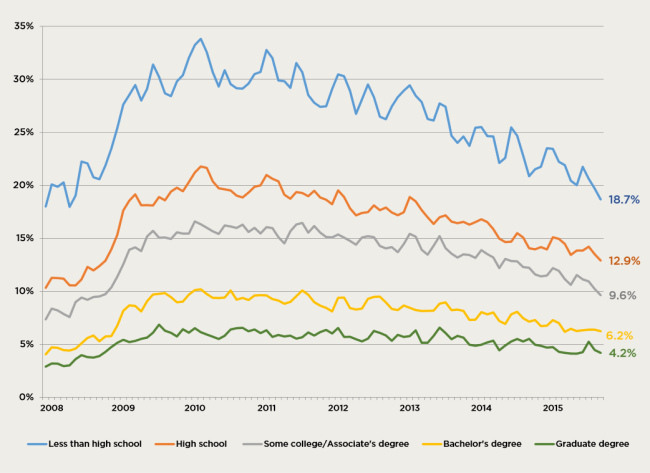

Underemployment rates by education level

Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce

The effect of the 2008 financial crisis and recession on the employment prospects of college graduates peaked in 2010, when the underemployment rate of college graduates -- a metric that includes both unemployed people and workers in part-time jobs, as well as those who have stopped actively seeking a job -- was more than 10 percent.

In the five years since, that rate has starkly declined, according to a new study, and those with college degrees continue to far outpace high school graduates in terms of finding steady work. This is especially true among Americans in minority groups, the researchers found.

Using data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey, researchers at Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce found that in 2015, college graduates with at least a bachelor’s degree had an underemployment rate of 6.2 percent. Those with graduate degrees had a rate of 4.2 percent. That’s compared to a 12.9 percent underemployment rate for high school graduates and an 18.7 percent rate for those who did not graduate high school. The rate for the adult population as a whole was 9.9 percent.

Earlier this year, a Bloomberg Business analysis of U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data found similarly encouraging results for unemployment rates. In February, the unemployment rate for bachelor's degree holders was down to 2.8 percent, compared to 5.7 percent for the adult population as a whole. It was the lowest rate since September 2008.

At the time, some pundits and politicians continued to question the value of a college degree, since the Bloomberg analysis did not focus on underemployment. Critics pointed to anecdotes of college graduates drowning in student debt while working part-time jobs at Starbucks. The Georgetown center’s study suggests that underemployment rates, too, are “substantially lower” for college graduates than for less-educated workers.

The effect a college degree has on underemployment rates is most evident among African-American and Hispanic adults. More than 33 percent of African-American adults who dropped out of high school were underemployed in 2015, compared to 17 percent of white high school dropouts.

As the level of education increases, the researchers found, the differences in underemployment rates begin to converge.

Of those who graduated high school, more than 21 percent of African-American adults were underemployed, compared to 14 percent of white high school graduates. The rate for African-Americans drops to 14.6 percent when they have an associate degree, then to 9.7 percent for African-American adults with a bachelor’s degree. White bachelor’s degree holders had an underemployment rate of 5.2 percent, and Hispanic adults had a rate of 8.4.

For African-American adults with a graduate degree, the underemployment rate in 2015 was 6.1 percent. Hispanics with a graduate degree had a rate of 6 percent, and white graduate degree holders had an underemployment rate of 3.8 percent.

While illustrating that a college degree vastly improves African-American and Hispanic graduates’ chances of finding employment, the center’s study does not include information about what kind of jobs the graduates end up taking. A study published in the journal Social Forces in February threw cold water on the idea that higher education is a great equalizer by showing that while a degree from an elite university improves all applicants’ chances at finding a well-paid job, the ease with which those jobs are obtained is not equal for black and white students.

“Most people would expect that if you could overcome social disadvantages and make it to Harvard against all odds, you’d be pretty set no matter what, [but there] are still gaps,” S. Michael Gaddis, the author of the paper and the Robert Wood Foundation Scholar in Health Policy at the University of Michigan, said.

A white candidate with a degree from a highly selective university, the study suggested, receives an employer response for every six résumés he or she submits. A black candidate receives a response for every eight. White candidates with degrees from less-selective universities can expect to get a response every nine résumés, while equally qualified black candidates need to submit 15.

Also troubling, the Georgetown center noted in a 2013 study, is how African-American and Latino youth -- especially those from low-income backgrounds -- are underrepresented at selective institutions to begin with, and overrepresented at open-access two- and four-year institutions.

Between 1995 and 2009, the 2013 study found, the number of Hispanic and African-American freshmen enrolling in college grew by 107 and 73 percent, compared to 15 percent for white Americans. At the same time, 82 percent of those additional white freshmen enrolled at the 468 most-selective four-year colleges, but just 13 percent of Latinos and 9 percent of African-Americans did. Nearly 70 percent of new African-American enrollments and 72 percent of the net growth in Hispanic enrollment during those years was at the open-access institutions.

The center’s new study, however, illustrates the importance of at least earning a college degree, the researchers said.

“More and more, a college degree is becoming a ticket out of the underemployment line,” Anthony Carnevale, director of the center, said in a statement. “It’s also clear that education is a pathway to reducing racial inequalities.”