You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A preliminary snapshot of the academic skills of students who are enrolled in a new, aggressive form of competency-based education is out, and the results look good.

Southern New Hampshire University used an outside testing firm to assess the learning and skills in areas typically stressed in general education that were achieved by a small group of students who are halfway through an associate degree program at the university’s College for America, which offers online, self-paced, competency-based degrees that do not feature formal instruction and are completely untethered from the credit-hour standard.

The university was the first to get approval from the U.S. Department of Education and a regional accreditor for its direct-assessment degrees. A handful of other institutions have since followed suit. College for America currently enrolls about 3,000 students, most of whom are working adults. It offers associate degrees -- mostly in general studies with a concentration in business -- bachelor’s degrees and undergraduate certificates.

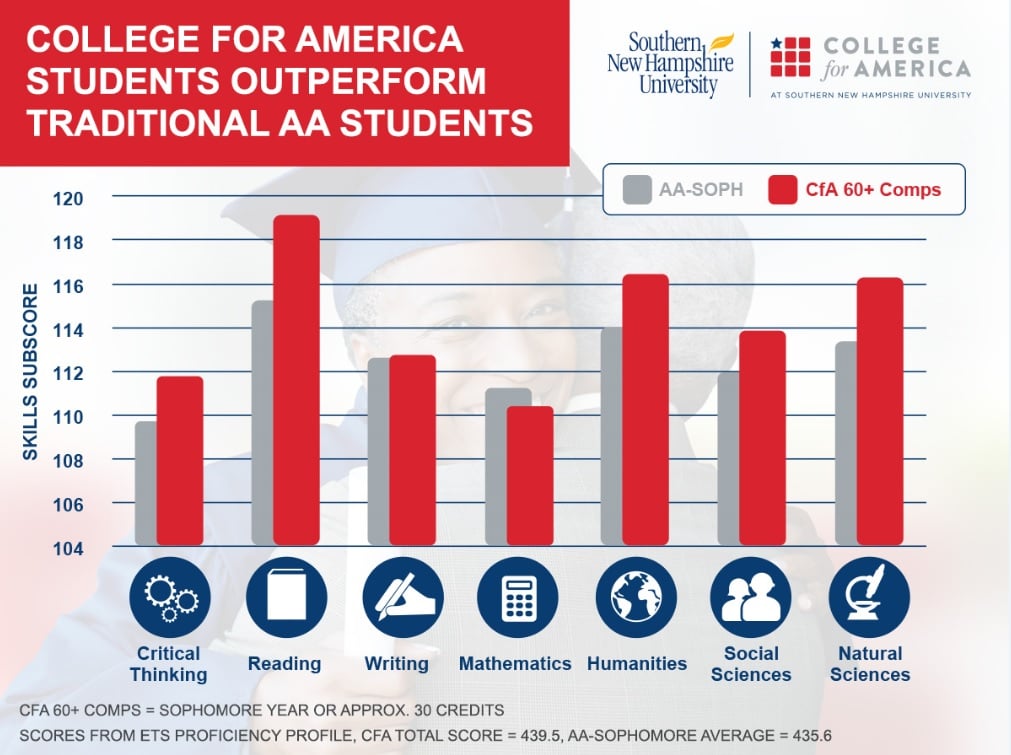

To try to kick the tires in a public way, College for America used the Proficiency Profile from the Educational Testing Service. The relatively new test assesses students in core skill areas of critical thinking, reading, writing and mathematics. It also gives “context-based” subscores on student achievement in the humanities, social sciences and natural sciences. The results could be notable because skeptics of competency-based education fear the model might not result in adequate learning in these areas.

“We wanted to be able to have a way of examining where the students are,” said Jerome L. Rekart, the program’s director of research and analytics. He added that they went with ETS for “external validation.”

Colleges can benchmark their results on the Proficiency Profile against those from other institutions. ETS features comparative data based on results from 7,815 students at 27 associate degree-issuing institutions, representing a wide range of colleges, programs and students.

Matthew Soldner, a senior researcher in the higher education practice at the American Institutes for Research, said the benchmark guide from ETS looked reasonable. (Soldner and AIR are working with a small group of institutions to gather early evidence about competency-based education’s effectiveness.)

The overall results from College for America placed its group of students at the 67th percentile (see chart, below). The students scored at the top -- the 100th percentile -- in reading and the natural sciences. College for America also looked good on the measure of critical thinking. It only lagged behind average in mathematics, and not by much.

“The students did quite well,” Rekart said. “It suggests we’re pointed in the right direction.”

Seeking Proof

College for America cautioned against reading too much into the results, which are based on a small sample from a program that was created less than three years ago.

“This really just scratches the surface of what our students are asked to do,” said Rekart, noting that the college’s academic programs are project based and that many of its students have not taken traditional examinations for years or even decades.

Even so, both critics and boosters of competency-based education are watching closely to see results from College for America and other direct-assessment programs. And Southern New Hampshire is eager to provide evidence about student achievement at its subsidiary. As Rekart said, the ETS comparison “speaks about transferability of the competencies.”

Amy Slaton, a professor in the department of history and politics at Drexel University, has written skeptically about the rise of competency-based education. She said the heavy workforce focus of some competency-based programs -- College for America relies on partnerships with employers as funnels for its enrollment -- makes it hard to glean much from benchmarking with traditional degree programs.

“This is not comparable,” she said. “We’re seeing a false equivalency.”

For example, Slaton said, the lack of traditional grading in direct assessment changes the calculus for students’ risk of failure. In a self-paced, self-directed environment, she said, students don’t fail, they just keep muddling along.

“You see definitions of learning that have really been gutted,” Slaton said. “That’s not higher education.”

Supporters of competency-based education, however, say their degree programs have the potential to be more rigorous. For example, a “gentleman’s C” isn’t possible in a competency-based program that requires mastery of a topic. If a student doesn’t demonstrate that competency, he or she doesn’t move forward.

Either way, competency-based education programs face plenty of pressure to show evidence of student learning.

“Everybody wants it. Everybody needs it,” said Alison Kadlec, senior vice president and director of higher education and workforce programs at Public Agenda.

And, as Soldner said, competency-based programs may have to clear a higher bar to gain acceptance. So the good news for College for America is that its preliminary student outcomes appear similar to (and even a little better than) those of more traditional associate degree tracks.

“Traditional programs have had years, decades and centuries to refine their pedagogies. Competency-based education programs are building from the ground up. Given how new so many competency-based education programs are, how reasonable is it to expect they’ll dramatically outperform traditional programs?” Soldner said in an email. “The curious thing isn’t that competency-based education programs are being challenged to show student learning outcomes; it is that an overwhelming number of traditional programs still aren’t.”