You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Science labs often hinge on the work of postdoctoral fellows, but this group as a whole is a relatively understudied. And that’s a problem, given the increased focus on fixing leaks in the graduate student-to-faculty pipeline -- especially for women and underrepresented minorities. A new study is shedding some light on the topic, suggesting that while biomedical sciences postdocs are getting advanced training through their positions, they’re actually less clear about their career goals than they were when they entered graduate school.

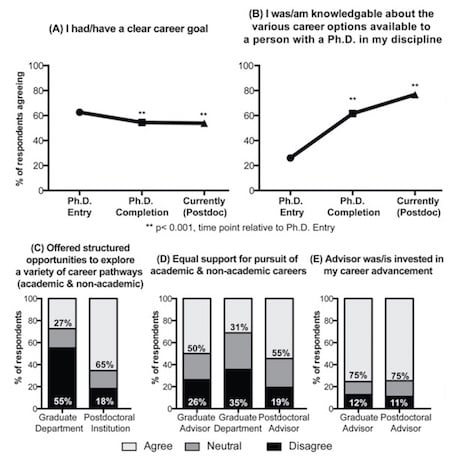

An online survey of 1,002 biomedical postdocs found that the majority were offered structured career development at their postdoctoral institutions, but less than one-third received it from their graduate departments. At the same time, postdocs from all backgrounds reported significant declines in interest in faculty careers at research-intensive universities and increased interest in nonfaculty careers.

“There is a misalignment between when postdocs are getting career development resources (i.e., during postdoctoral training), and when they are making up their minds about their careers (i.e., graduate school),” the study’s lead author, Kenneth D. Gibbs, a cancer prevention fellow at the National Cancer Institute, said via email.

The takeaway? Universities “should enhance efforts to ensure that robust career development is part of Ph.D. training,” Gibbs said. But that’s more than just providing information through seminars and individual development plans.

“Our results show that even though people are getting more information as their training increases, they are not getting more clear,” Gibbs said. “More has to be done to ensure that people have ample space and time to think through their career options -- not only what is out there, but explore what would be the best fit for them.”

Differences in interest in faculty careers at research universities across gender and race are not explained by research productivity, research self-efficacy or adviser relationships, the study notes. So efforts to increase the number of women and minorities in the sciences should look at other structural factors that are disproportionately leading these groups away from faculty careers.

Gibbs said studying postdocs matters because these fellows are “critical contributors and drivers of the research enterprise.”

“To put it another way, the health of our research enterprise depends on a pool of people we know very little about,” he added.

The study, out this week in CEB Life Sciences Education, is based on an Internet survey of U.S. postdocs starting in late 2012. The final sample is about 9 percent of all eligible respondents -- meaning postdocs in the life sciences, bioengineering, neuroscience and psychology -- and 19 percent of underrepresented minority background postdocs. (Note: This sentence has been updated from a previous version.) The data set was the basis for another study published by Gibbs last year in PLOS, which suggested that female and minority Ph.D.s in biomedical fields are more likely than others to lose interest in faculty careers while earning their doctorates.

Findings of this new study include that postdocs reported entering Ph.D. training poorly informed about career options. Just 26 percent of respondents said they entered graduate school knowing what they could do with their Ph.D., for example.

Over time, they become less clear in their career goals: clarity about what they want to do dropped from 63 percent at Ph.D. program entry to 54 percent at entry to postdoc. Very few postdocs also reported getting career development in graduate school -- just 27 percent. But 65 percent reported getting it during postdoctoral training. That’s perhaps good news to the many critics of postdoctoral fellowships -- including the authors of a landmark 2014 study -- who say that they’re more a form of cheap labor than true, advanced education.

Gibbs's co-authors for this study are John McGready, an associate biostatistician at Johns Hopkins University, and Kimberly Griffin, an associate professor of higher education at the University of Maryland at College Park.

All social groups saw significant declines in interest in faculty careers at research universities, but these declines happened more quickly for women and minorities -- who mostly lost interest during graduate school -- than for white and Asian men, who lost interest as postdocs.

The percentage of underrepresented minority women who reported that they felt they belonged socially in their graduate labs and departments was 13-21 percentage points lower than their peers. Just half (48 percent) of underrepresented minority women postdocs reported feeling that they belonged socially in their graduate departments.

Women reported lower levels of confidence in their abilities as independent researchers, even at the same level of productivity.

While things like research productivity, adviser relationships and confidence in one's ability matter, Gibbs said, “they don't explain the differences we see across gender in career interests. The career interests formed in graduate school are by far the biggest predictor of what one wants to do careerwise, and these career interests differ even if other important factors (publication record, mentoring, confidence, etc.) are the same.”

Career Clarity, Advancement Among Postdocs