You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Performance-based funding in higher education is spreading, with 35 states either developing or using formulas that link support for public colleges to student completion rates, degree production numbers or other metrics.

The resulting debate over whether performance funding works is heating up, too. But a new report from HCM Strategists makes the case that there is great variation among the policies in those 35 states. It seeks to classify four types of formulas to help inform policy makers, researchers and higher education officials.

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which supports performance-based funding, paid for the report from HCM, a public policy and advocacy firm. Martha Snyder, a senior associate with HCM, wrote the paper. She has worked with policy makers in several states on performance funding.

Snyder said blanket statements about those policies tend to drown out the nuance. The report tries to move past this type of argument by distinguishing between state approaches and by describing which ones work best.

Four broad types of performance-funding models have emerged, according to the report, which uses the term “outcomes-based funding,” the preferred nomenclature among advocates.

The report assigns types to policies based on increasing levels of “sophistication and adherence to promising practices.” Type I, for example, covers some of the earliest approaches, which do not include completion goals and only affect low levels of funding -- less than 5 percent of public college budget contributions. But Type IV features at least 25 percent of funding and factors in outcomes for underrepresented students.

“These typology characteristics reflect commonly articulated and research-informed design and implementation principles,” the report said.

A key point in assessing whether performance-based funding works, according to HCM, is to first determine how much money is at stake.

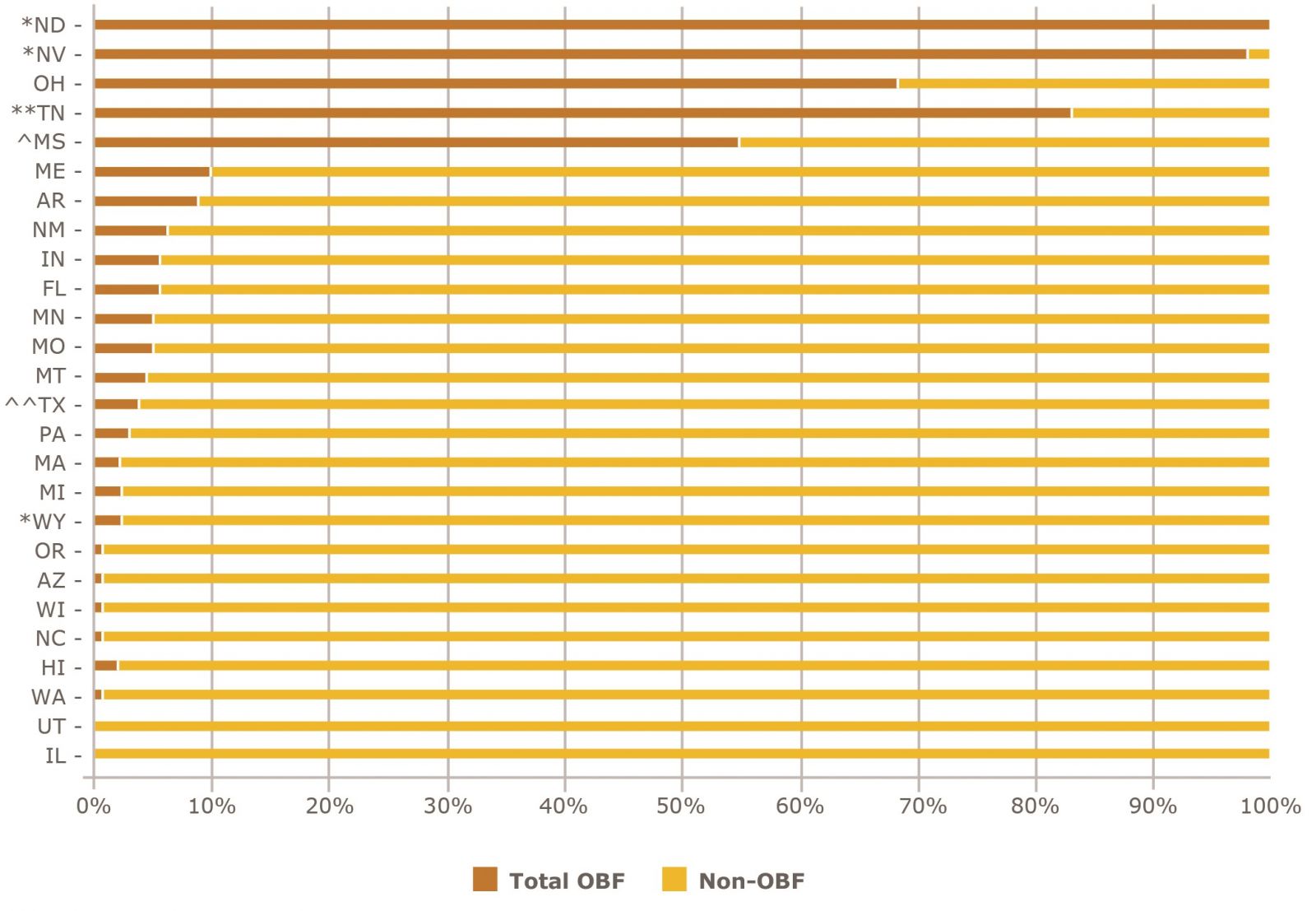

While 26 states have performance policies on the books, only 5 tie more than half of overall state support for public institutions to the formulas. Those states are North Dakota, Nevada, Ohio, Tennessee and Mississippi.

It’s a steep drop-off after that group -- the other 21 link less than 10 percent of state funding to performance.

That money doesn’t go far on a per-student basis. The report said states with some performance-funding average $810 per student in outcomes-tied spending. Tennessee and Ohio both top $4,000 per student, while Washington is $23 and Texas is $377.

The share of performance funding should be large enough to gain attention, shape priorities and influence actions, according to the report. Others, however, would prefer that experiments with funding formulas are limited, and seek to sway colleges' behavior without risking large pots of state money.

Critics Weigh In

The Gates Foundation is a prominent supporter of completion-oriented accountability in higher education. Some skeptics likely will be unmoved by a Gates-funded report in its attempt to reframe the debate around performance funding.

However, two academics who have produced studies that cast doubt on the efficacy of performance-based funding said the HCM document will be helpful.

“They’re offering some guidance and some classification themes,” said Nicholas Hillman, an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, who studies higher-education finance and policy.

David Tandberg agreed. Tandberg, an assistant professor of higher education at Florida State University, said he appreciates that the report is distributing information about the program design of funding models.

He praised its use of portions of studies by Kevin J. Dougherty, an associate professor of higher education at Columbia University’s Teachers College who is a senior research associate with the university’s Community College Research Center. But Tandberg also said he was disappointed that the study did not draw from the growing body of quantitative research on performance-based funding.

"We cannot expect to improve public policy if we choose to ignore the results of rigorous evaluations,” Tandberg said in an e-mail.

In response, Snyder said much of the existing research is about funding models that no longer exist, weren't focused squarely on completion and were done on the margins. She also said that some of those studies "make broad claims that reach beyond the findings."

The HCM report in part seeks to shape the conversation by pointing to design principles that it said research has shown to work best. Many of those lessons have been learned from the trial and error of early funding formulas. States can use these emerging “best practices” to develop their own models, according to the report, or to update existing policies.

The report’s recommendations include establishing a consensus around goals before developing a policy, making funding meaningful and secure, identifying limited and measurable metrics, including all institutions while allowing for differentiation, rewarding progress, and evaluating and adjusting.

“The analysis of state funding policies must continue in an effort to inform these considerations and understand the most effective way to direct their investment in higher education,” the report concludes. “Moving toward results-based policies may require fundamental shifts in resources and mind-set -- but our students deserve no less.”

For his part, Hillman said deep questions plague performance-based funding. A big one, he said, is that it’s unclear if the use of incentives to move institutional behavior is effective.

“The design oftentimes isn’t the problem,” said Hillman.

Yet both Hillman and Tandberg said further discussion is warranted.

“Hopefully moving forward we can establish a better dialogue between independent researchers and those advocates who are working with the states on such issues,” Tandberg said. “These are very important and high-stakes issues that deserve serious consideration and empirical evaluation.”

.jpg)