You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Wake Forest

Wake Forest University is looking to find a new way to measure the “well-being” of its students and alumni.

The university’s administration and a few faculty members have been working on a longitudinal survey that is designed to determine whether the college is helping its students find meaning and purpose in their lives, though questions are also likely to include more practical matters, such as post-collegiate pay.

The survey, which is perhaps a year or more away from widespread deployment at the private university in North Carolina, is a new entrant into a small but potentially growing field of measurements designed to find out more about students.

The measurement attempts to contrast with those being explored by the federal government, which would measure completion, salaries after graduation, recruitment of low-income students and more, as well as with other efforts to quantify college competitiveness and campus life by the likes of U.S News & World Report and the Princeton Review.

The results of another such survey by Purdue University and Gallup are set to be released next week. The Gallup-Purdue Index focuses on a set of factors that are supposed to correlate with a “great life,” such as about work place and community engagement, personal relationships, physical fitness, sense of purpose and happiness, and economic management and stress. A few other surveys – including the Freshman Survey developed by the University of California at Los Angeles and the American College Association’s National College Health Assessment – measure a few but not all of the things Wake Forest is after (although for entering or current students).

Wake Forest wanted something even more nuanced than it found the Gallup-Purdue project to be, said its vice president for student life, Penny Rue. The university is concerned not only about students in college – who are suffering from stress, anxiety and trouble sleeping – but alumni who enter a post-collegiate economy of “permanent whitewater.”

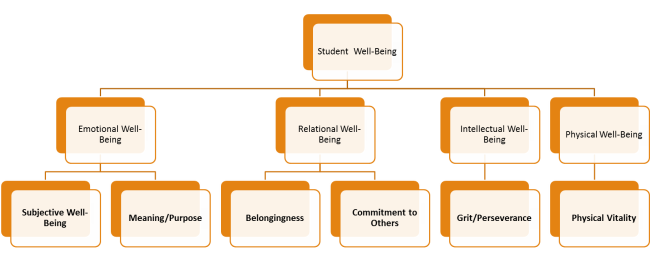

“Our experience is that with this age group particularly, we really felt the need to split out issues of commitment to others, belongingness, meaning and purpose – it’s just a richer, deeper look at issues we think are particularly relevant,” Rue said.

The university has six main areas it wants to explore: self-reported well-being; the level of meaning and purpose students find in their lives; “belongingness”; commitment to others; grit and perseverance; and physical health. The survey might include statements to respond to, such as "I am a good person and live a good life," "I often feel left out," "I am satisfied with my life."

Wake Forest is still working out what the survey will look like. The university wants to find something that not only models student well-being but provides actionable information, like data that can be used to improve the university’s first-year experience programs.

But it will also be used to keep tabs on alumni.

“I think more and more universities are going to be educating alums rather than just entertaining them – we’re going to redefine what an alum means,” Rue said.

For the survey to work, it has to be able to figure out what about a person the university can change and what it cannot, said Sara Dahill-Brown, an assistant professor of political science who is helping to develop the tool.

“Ideally, we want our measurement to be able to differentiate between aspects of your well-being that are more fixed and differences of your well-being that the university can actually move,” she said.

The survey is now being based in part on the work of Eranda Jayawickreme, an assistant professor of psychology who studies well-being. He received grant from the John Templeton Foundation to study student well-being, but the project happened to dovetail the university’s interest in assessing its own performance. Andy Chan, the vice president for personal and career development, helped secure money to expand the project.

Jayawickreme said Wake Forest wanted its own instrument because the surveys he saw, like the Gallup/Purdue Index, focused on “justifying the cost of higher education” rather than the totality of a person’s life.

Brandon Busteed, who leads Gallup's education work, said the firm's work is definitely not about justifying the cost of higher education and is aimed at how to improve the quality of it — plus, he said, Gallup's higher ed well-being work is not yet public, so he's not sure how anyone can accurately characterize its nature. He wished Wake Forest the best as it comes up with its own definitions.

"But Gallup has literally written the book on well-being after decades of work on this area," he said in an email.

Jayawickreme said if universities begin to measure well-being, they will begin to try to make changes that improve students’ lives.

“By measuring these dimensions of well-being over time, universities will start caring about which to improve upon,” Jayawickreme said.