You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

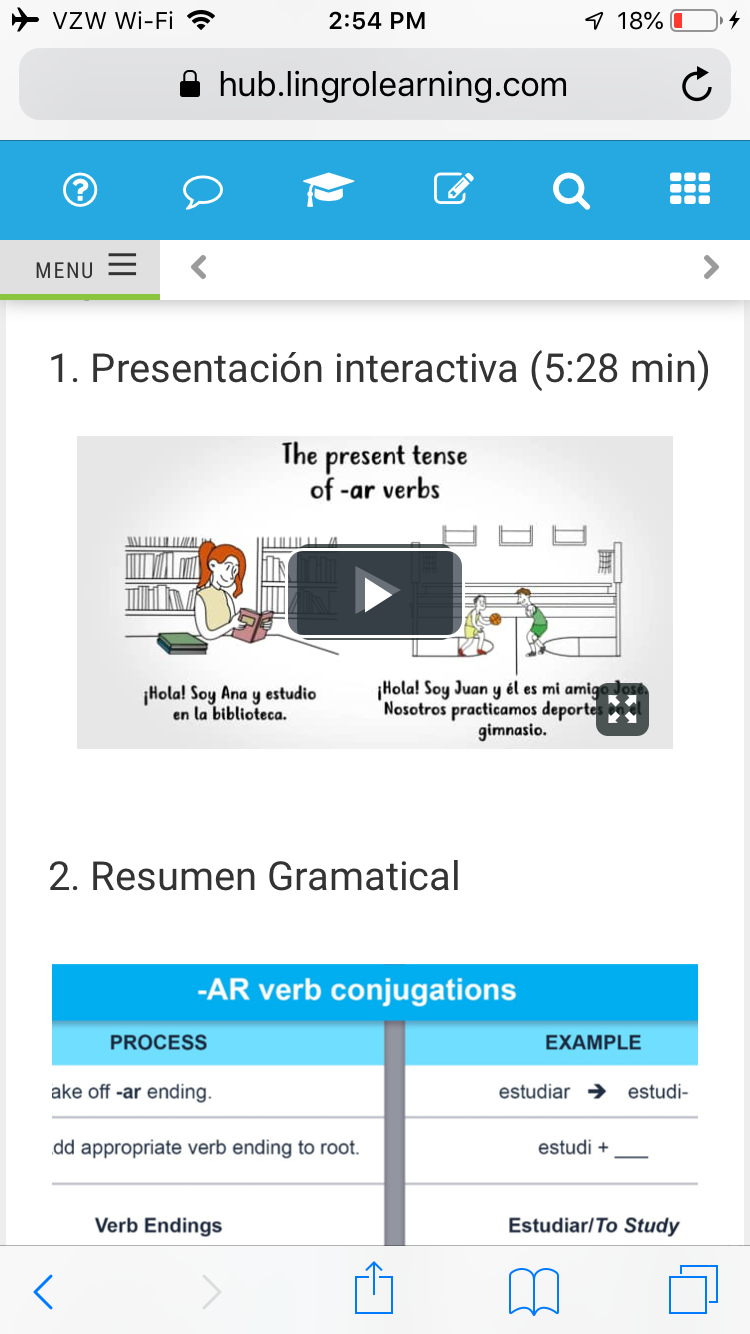

Courtesy of Steve Debow/LingroLearning

Trial and Error is a recurring feature from “Inside Digital Learning” that examines the successes and struggles of technology initiatives on campuses and in classrooms. Have ideas for future columns? Send them to mark.lieberman@insidehighered.com. And be sure to comment below the story with thoughts and ideas for this institution.

The Players: Amy Rossomondo, associate professor and director of the Spanish language program at the University of Kansas. Gillian Lord, professor of Spanish at the University of Florida. LingroLearning, a foreign language educational technology company.

The Players: Amy Rossomondo, associate professor and director of the Spanish language program at the University of Kansas. Gillian Lord, professor of Spanish at the University of Florida. LingroLearning, a foreign language educational technology company.

The Idea: In 2012, Rossomondo and Lord, who had interacted briefly at conferences but never worked together, got separate phone calls from the foreign language team at one of the major publishing companies. The team wanted the two to collaborate on a foreign language textbook with a digital component -- a perfect fit for Rossomondo’s experience with open-access publishing and Lord’s interest in computer-assisted language learning.

The most conventional option was to write a textbook in print and then translate it online. Rossomondo and Lord wanted something more dynamic. The other end of the spectrum would be a computer program like Rosetta Stone, which allows students to be self-sufficient and eliminates the instructor.

Neither appealed to Rossomondo and Lord, who spent much of the early years of the project thinking about how to advance foreign language instruction into the modern age.

Early Efforts: Three years passed. The development process was challenging.

“We would figure out what we wanted, we’d come back and find out the technology can’t do that,” Rossomondo said.

Lord’s vision was for a truly adaptive learning platform that would speed up instruction for students who demonstrated competency and slow it down for those who needed more help. But pulling off a program of that complexity “became mathematically insurmountable,” she said, thanks to the number of permutations that the authors would have to consider ahead of time.

Another idea involved asking students to answer questions about a video. But the publisher's technology apparatus wouldn’t allow for a split screen with a video on one side and a quiz on the other. Lord also wanted the program to be organized as “concepts” rather than “pages,” but that was a challenge for the publishing company, which was still approaching the project as a textbook.

“It’s really hard to imagine something that you’ve never seen before,” Lord said.

More From “Trial and Error”

Medical college translates face-to-face games to online format.

Revamping instructional design and the semester schedule.

Creating virtual reality “as memorable as the O. J. Simpson trial.”

Students and alumni lead an OER factory.

Language learning textbooks tend to be formulaic, Lord said. Moving in a different direction isn’t easy. Eventually the authors and the publisher parted ways, mutually recognizing that they couldn’t quite reconcile the vision with practical reality.

Changing Course: Lord and Rossomondo considered creating an open-access resource, but they found that storing student data would have been impossible in that format, which generally doesn’t have room for a private instructor grade book.

“In theory content could be created and deployed within existing LMSes, but there is not a seamless solution that would provide an out-of-the-box learning program that instructors can easily manage,” Rossomondo said.

OER also doesn’t offer built-in tech support, which would make troubleshooting student concerns too difficult for instructors to manage.

Instead, they reconnected with some of their former publisher collaborators, who had left the company to start a new venture, LingroLearning, that combines digital technology and foreign language instruction. Coupled with the company’s partner platform Junction Education, Rossomondo and Lord had finally found a team with the technological capabilities to realize their vision and expand upon it.

“When we got the opportunity to work on the project on our own terms, and not within the framework of one of the big publishers, we were able to explore a lot of new avenues and do things differently,” Rossomondo said.

“It was a little scary,” Lord said. “It wasn’t like going with a recognized name and a recognized platform.”

They wanted to focus on providing opportunities to students to have an audience aside from the instructor, so they created a social media "portfolio" on which students can test out their new language skills. They also wanted to capture students who might be skeptical of the value of foreign language instruction, by connecting the material they were learning to real-world situations.

The company’s four co-founders all worked previously at Pearson or McGraw-Hill but figured that they could have more impact on the language learning app from a start-up -- creating something from scratch rather than reinventing the wheel, according to Steve Debow, CEO of LingroLearning. The production process for what eventually came to be known as Contraseña (“password” in Spanish) ended up taking 18 months, Debow said.

Debow’s team’s main contributions included editing content, engineering the eportfolio infrastructure, storyboarding and producing video materials.

“We played the role that any ed-tech creator/production company would play. Everything from perception to final outcome,” Debow said. “They had the ideas, they did the writing, but then they also got the ideas from new functionality based on the interaction with our team.”

Debow said determining the cost of the project would be difficult given its numerous iterations.

Once again, Rossomondo and Lord’s ambitions clashed with the technical possibilities, like asking for embedded sound on widgets that couldn’t support it. On the other hand, the tech partners warmed to some of their more idiosyncratic ideas, like a diagram of a mouth moving to form a letter or syllable.

The team also got ideas from outside sources, like the Center for Applied Second Language Studies (CASLS) at the University of Oregon, which helped the company build a portfolio tool where assessments could be posted.

The End Result: Five institutions, including Rossomondo and Lord’s employers, have replaced traditional textbooks with Contraseña this semester. Rossomondo and Lord called everyone they knew to ask if they were interested in using the platform at no cost to them. Students pay no more than $75 per semester to use the program -- not a no-cost solution as the team had originally hoped, but a significant discount from the more expensive traditional textbooks students are often forced to buy, even if they only use a fraction of them.

The program allows instructors to teach in a flipped format, with didactic language learning happening online and dynamic conversation taking place in the classroom. Students are required to produce videos at the end of each lesson demonstrating their mastery of the material.

Those videos get posted to an online portfolio outfitted with the ability to like and comment on posts. Some lessons proceed in a "choose-your-own-adventure" format, with several different possible outcomes.

Lord and Rossomondo’s impression so far is that students prefer this format to the more traditional alternative.

“A lot of times we see some less than ideal motivation in those beginning classrooms,” Lord said. “The fact that students are really enjoying it … is really encouraging.”