You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Students in the University of Central Florida’s College of Business this week have gotten more than 1,800 signatures on a petition criticizing the college’s recent shift to a blended and active learning classroom model that some students describe as onerous and not conducive to learning.

The business college, meanwhile, is standing behind its changes, arguing they're sound and well intentioned from a pedagogical perspective, and more well liked by students than the petition suggests.

Students who signed the petition, first reported by UCF's student newspaper Knight News, expressed frustration with the college’s "reduced class time" format, in which students work on group projects during five in-person sessions throughout the semester and complete the bulk of their learning outside class by reading an online textbook, watching three-minute instructional videos created by textbook publishers and faculty members, and completing textbook assignments.

Under the previous model, professors delivered two weekly 75-minute lectures students could attend in person or watch online synchronously or asynchronously. The new model eliminates the lecture element and requires students to learn much of the course content on their own, with 75-minute face-to-face sessions five times during the semester, designed to apply what they've learned to concrete activities.

The petition was written by Michael Wensinger, a junior finance major who now serves as leader of the Knights of College of Business Administration Reform group on campus. (The college dropped "administration" from its name in 2016.)

The coalition formed in a GroupMe text thread that Wensinger started a few weeks ago to vent about the reduced class time format. Wensinger and other students said they were blindsided by the news this semester that all but two of the college’s 14 core courses, required for admission to a major, will be taught exclusively in this format. The college started testing the modality in four courses last summer and has slowly spread it over the last year, according to Paul Jarley, who has served since 2012 as dean of the business college.

“A lot of students don’t learn that way or retain” in the reduced class time model, Wensinger said. “Students are having to teach themselves.”

Within a few days, more than 300 students had joined the ad hoc group, he said. Wensinger has established a “facilitating committee” of 12 students to “help lead the movement,” he said. The group plans to attend a town hall meeting next week with the university's president and to begin posting fliers around campus this week, according to Wensinger.

The controversy around the new format points to deeper challenges for the enormous and still-growing university, which seeks to add teaching modalities to accommodate as many students as possible, but risks outpacing its capacity. Jarley said offering courses in multiple modalities and allowing students to choose, for instance, would be too costly for the institution to do without burdening students in other ways.

"The way that we’re able to provide access and affordability to our students is we do things at scale," Jarley said. "If I were to lose that scale, I would lose some of that affordability for students, and I would lose some of that access. It would cost [students] more. Or I would have to really increase class sizes in upper-division courses and reallocate resources that way."

Origins of the Approach

Central Florida -- one of the country's largest institutions, with more than 64,000 students -- was one of the first universities to invest heavily in blended learning, with courses offered for the last two decades both in person and online via lecture capture. University administrators have long regarded the hybrid format as the most popular among students, according to Kelvin Thompson, executive director for the institution’s Center for Distributed Learning. The university also has a mandate from the state government to offer diverse education options.

But according to Jarley, data reveal that many business students in blended classes who opt not to attend face-to-face also never watch the recorded lecture videos -- or they wait weeks after the recording to watch them, perhaps to cram for an exam. During the 2017-18 school year, an average of 46 percent of the 3,400 students enrolled in lecture-capture courses watched fewer than half the videos in their course, according to a university spokesperson.

Those classes tend to have between 800 and 2,000 students, Jarley said. The university doesn't collect attendance data on the in-person sessions because they're not mandatory, a spokesperson said, adding only that "faculty [report] lecturing to largely empty rooms." The business college also didn't provide to "Inside Digital Learning" data on student performance in lecture-capture courses.

The business college, which enrolls 8,500 undergraduate students and 1,000 graduate students, was the first of the university’s schools to implement the reduced class time format, developed last year by the Center for Distributed Learning. Some professors have incorporated adaptive learning into the online portion of the classes so that each student's experience is tailored to their learning needs. Jarley hoped eliminating instructor-led lectures would let students spend more time engaging with their peers and gaining a deeper understanding of the material.

“It’s important that our students get the soft skills and the decision-making skills they need in order to succeed in the workplace,” Jarley said. “That was very hard to do in the lecture-capture format because they’re just being lectured at. They’re not actually doing anything.”

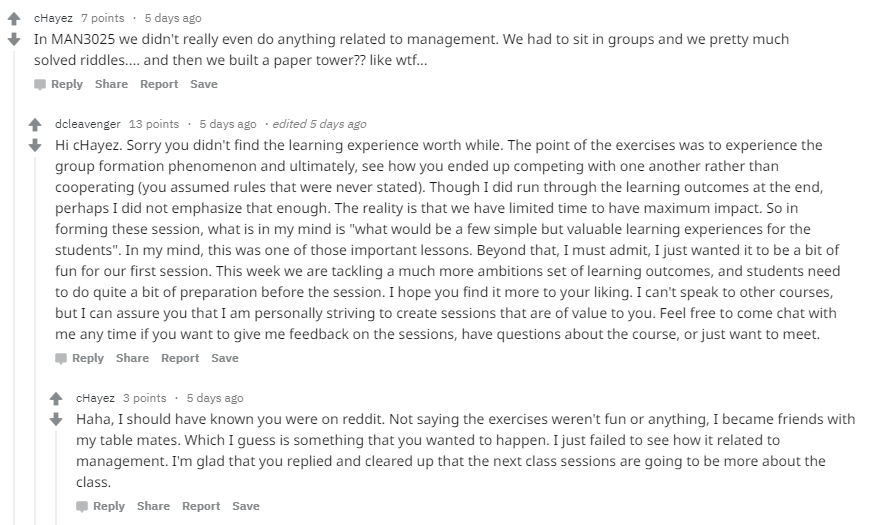

But some students bemoan the drastic step of ending the weekly sessions with instructors altogether. They believe they learn more when they have more opportunities to engage with the professor in person about the learning material, rather than learning most of the material online and completing a group project they perceive as tangential.

Under the lecture-capture model, students could spend up to about 30 hours in a physical classroom with an instructor (assuming they actually went). Now the maximum class time is approximately 6.25 hours, and in some cases the professor might not be present for all of them.

“I’ve been in lecture classes and I’ve also been in reduced seat time classes,” said Kelly Kennedy, another member of the COBA Reform group. “It was way more beneficial having face-to-face interactions than speaking to my professor five times in a whole semester.”

Kennedy said students are balking at the group project assignment, which isn't directly connected to exams. She and some of her peers would prefer to use that time to discuss course content with the instructor.

Students in some classes also told “Inside Digital Learning” that online textbooks provided by McGraw-Hill Connect, which cost more than $100 each, have been glitchy at times, and that in some cases, the first face-to-face session this semester was run by teaching assistants.

“I’m a straight-A student now struggling to get B's,” Wensinger said. “I’m very nervous and stressed out all the time about that.”

In addition to offering more structured in-class activities, this format frees up the business college's 135 full-time faculty members for more sections with smaller class sizes in the business school’s upper-level classes, Jarley said.

Wensinger and his peers say they know some students who like the reduced class time format. But students who signed the petition say they want the university to provide more than one modality option, or to listen to their suggestions for improving the reduced class time format.

John Nazario, a junior business marketing major, thinks the format could work with a few more class sessions focused on discussion, or if the courses were offered entirely online. He told “Inside Digital Learning” Wednesday that he was strongly considering scheduling an appointment with his adviser and switching out of the business school to a new major like digital media.

“If I would have known about this, I wouldn’t have studied at UCF,” Nazario said. “I would have gone to a private college to do something else.”

Navigating Student Feedback

Jarley said he and his colleagues are thinking about ways to explain the reduced class time format more clearly to students during orientation, particularly for transfer students from community colleges, where class sizes are significantly smaller and engaging one on one with a professor can happen more frequently.

According to Jarley, two-thirds of more than 3,200 students who responded to surveys at the end of the last school year rated the reduced class time format “excellent” or “very good.” The business school also trained student observers to evaluate the effectiveness of the group projects sessions and asked business school department chairs to sit in on several sections.

“We were pretty pleased with those outcomes,” Jarley said.

Students have been agitating to air their concerns for meetings with business college administrators. Jarley said he’s open in theory to holding such a meeting, but he’s concerned about ensuring that the students in attendance represent the wide range of opinions.

“I wouldn’t rule out down the road doing some focus groups with specific students,” Jarley said.

“Reduced class time” is something of a misnomer, he points out -- students previously could have watched all of the semester's lectures online, but now they’re required to attend five in-person sessions. When he taught in lecture style with optional classroom attendance, an average of 50 students out of 800 or more in a class came in person each week. Several hundred attended the first couple sessions, he said, but the numbers dwindled significantly afterward.

Now he has fewer class periods per semester to manage, but each group project session has 200 students, and he oversees several sections throughout the week.

Still, he thinks mandating face-to-face class time is worthwhile, given that he often felt like students weren’t paying much attention to his lecture videos or inclined to go above the minimum requirements.

“In my experience when I’ve done extra activities, I’ll have 150 urgent hands in the air, ’Yes I’ll do that,’ then 30 come,” Cleavenger said.

Students don't always avoid lectures out of laziness, according to Kennedy. She said she was turned away from the first day of a core class last semester because the 300-seat lecture hall was full. She continues to prefer attending class in person but was frustrated to drive from her home 30 minutes from campus only to find she'd have to watch the lecture online.

"Students shouldn’t be turned away from classes they’re paying for," Kennedy said.

Petition signees have also raised concerns about price. In-state undergraduates in the business college pay $212.28 per credit hour, and out-of-state undergraduates pay $748.89 per credit hour. Both groups also pay an $18 per credit hour distance-learning fee for hybrid courses. In accordance with Florida state law, the university can charge the distance-learning fee for reduced class time courses because less than 20 percent of instruction takes place face-to-face.

The need for teaching assistants to walk around class sessions with several hundred students means the reduced class time model costs the university more money than the lecture-capture format, Jarley said. He did not provide a specific cost comparison in time for publication.

Measuring Long-Term Outcomes

As of this fall, only two of the business school’s core courses have not shifted to the reduced class time format. One of the two untouched courses is separately set to be revamped with a new content focus, and the other is the capstone course, for which engagement with lecture capture tends to be higher than average, Jarley said.

None of the university’s other colleges have yet offered classes in this modality, according to Thompson -- though the College of Arts and Humanities has three reduced class time sections of one philosophy course in the works for next semester, he said.

Jarley said instructors haven’t reported a significant increase this semester in students signing up for tutoring sessions or meetings during office hours.

Exam scores thus far in the reduced class time courses haven’t been substantially different from those in the lecture-capture format, according to Jarley. He believes gains are likely to start showing up after four semesters offering the format, which would mean increases would appear after this semester.

Students involved in the petition might not be willing to wait that long. But Jarley thinks an experiment only takes shape over time.

“I think whenever you make a change of this kind, which is not only a change in format but a cultural change, you’re changing the perceptions of what the student’s role is in the classroom, and what the faculty’s role is in the classroom. I think you have to expect that people are going to have an adjustment process to that, that it’s not going to come naturally to them,” Jarley said. “That’s not a reason that should stop you.”