You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Istockphoto.com/LeoWolfert

Adam Nemeroff, an instructional designer in Dartmouth College's department of academic and campus technology services, admits he has “super-complicated and conflicted” thoughts about the role of technology in ensuring that digital courses and curricular materials are fully accessible to all students. He’s seen his institution and others in recent years talk more about accessibility and invest in digital tools to address concerns head-on. But he thinks there’s a downside to being too tool focused.

“If you’re starting with the technology, you’re doing it wrong,” Nemeroff said. “In my experiences, it’s mostly an issue of perspective to show where these problems could arise for specific individuals and people really understanding that.”

Institutions have begun taking accessibility more seriously as the threat of litigation has grown, enforcement has grown more stringent and challenges for students have garnered more mainstream discussion. Learning management systems like Blackboard and Canvas are among the companies offering products and services billed as early-warning systems and even antidotes to accessibility shortcomings. Institutions are striving in greater numbers toward universal design for learning, which emphasizes multifaceted tech-driven approaches to improving students’ access to learning.

Technology has limitations, of course. Institutions rely on it so heavily so that some have considered joining forces for a more unified quality-review process. Most observers agree human intervention will always need to remain part of the accessibility conversation, given the diverse array of definitions of the term. Thus far, however, digital tools have proved more successful at identifying superficial failures in courses than at digging into the nuances that make courses more deeply accessible to a wider range of students.

“I have not yet found a digital tool that replaces human knowledge and experience when it comes to accessibility,” said Eric Moore, a UDL and accessibility specialist in the University of Tennessee's office of information technology. “I liken it to a warning light in their car -- it lets you know there’s an issue, but you still need to know whether that’s a serious thing or something that’s not that big of a deal.”

Ask a tech company the same question, though, and the answer is a shade more optimistic.

“I think [institutions] would like to have a magic button to push to make all content accessible,” said Jared Stein, vice president of higher education strategy at Canvas. “We’re still a ways away from having that magic button. But it’s feasible.” Stein adds a note of caution, though: “Even if we have that magic button, I don’t know that that by itself is necessarily the right solution.”

What Falls Under “Accessibility”?

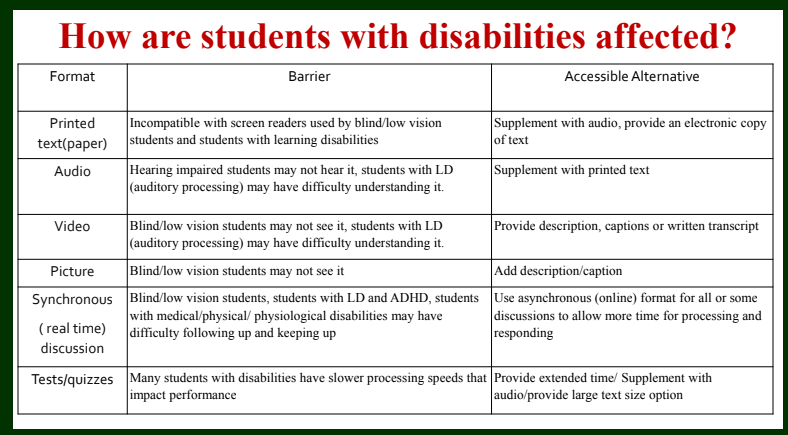

The first challenge that comes with addressing accessibility concerns is a matter of defining terms.

Broadly, “accessibility” refers to allowing individuals with disabilities to use a product or system as easily as someone without those disabilities. Estimates put the number of students in higher education with disabilities at around 10 percent -- though that number is complicated by the fact that many students with disabilities don’t feel empowered to share those details with professors and administrators.

“If I'm using a tool to make my content accessible, or even designing a course with UDL in mind, I still need to understand that I could have a student come into my class with an accommodation request I hadn't planned for -- and that will always be the case,” Sonka said.

Under a federal law established in 1973, organizations are required to ensure equal accessibility for people with disabilities. That law and subsequent federal guidance served as the basis for a 2013 case in which a blind Louisiana Tech University student successfully sued the institution because his professor didn’t provide an alternative to an internet-based application he couldn’t use. The judge ruled that the institution needed to allow that student and all others to be integrated into a class, rather than separated based on availability.

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines, updated most recently in 2008 by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), now offer a detailed road map for ensuring compliance with federal law. But, Sonka points out, “even if you fully meet WCAG 2.0 requirements, content can still be inaccessible" for students outside the disability categories conventionally associated with accessibility.

Where Technology Comes In

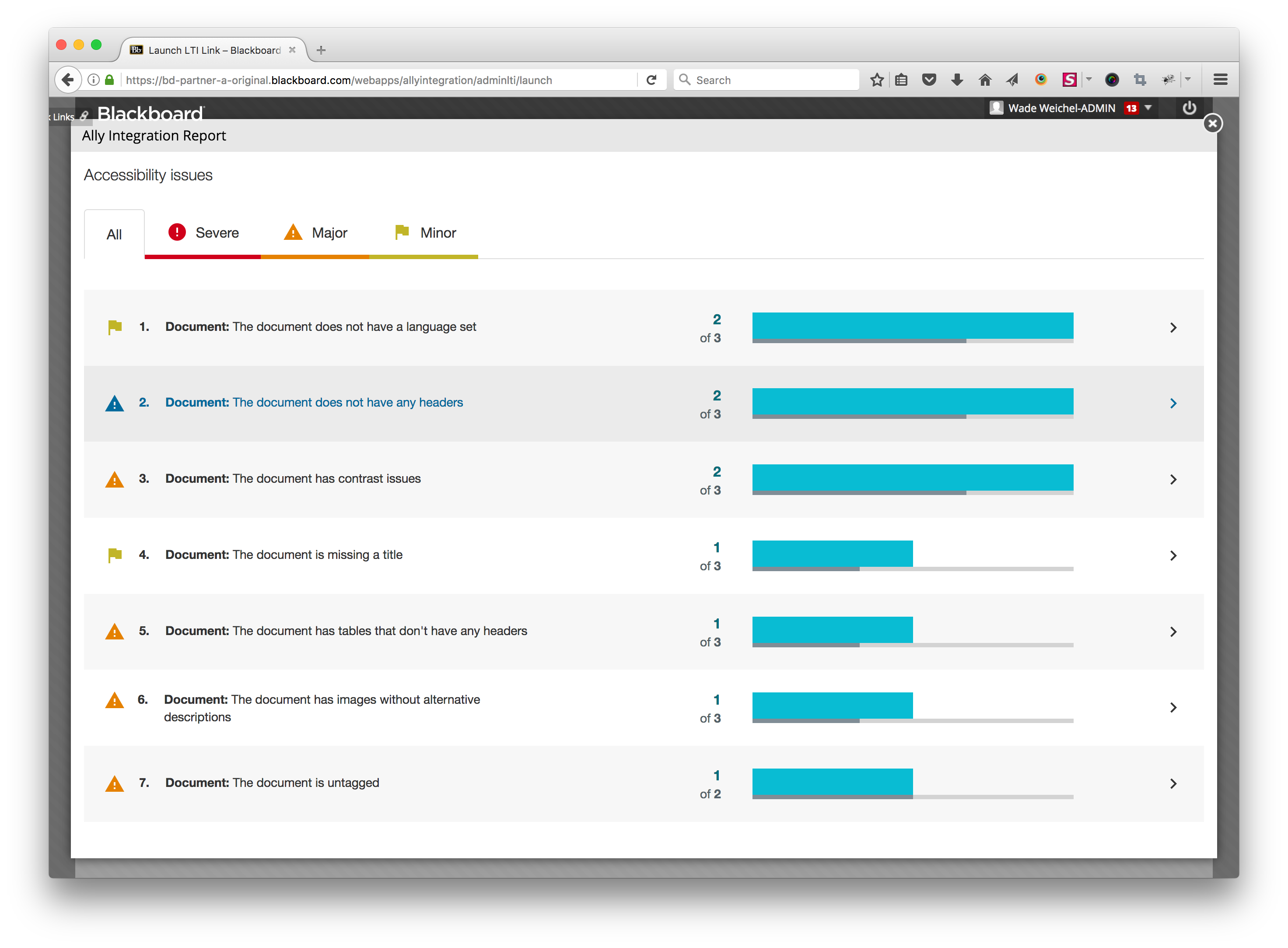

Tools like Blackboard Ally, Canvas Accessibility Checker and the open-source Udoit from the University of Central Florida offer opportunities for institutions to quickly ascertain their accessibility progress, both in individual courses and as a whole. These tools are embedded within an institution’s learning management system and provide reports on digital course materials.

Ally runs materials through a checklist of common accessibility issues and assigns an “accessibility score” between one and 100 to each. The goal is to alert an institution or instructor of areas where it needs improvements, suggest a road map to greater accessibility, and in some cases generate additional resources (such as mobile versions of documents) that can make a course more accessible.

“Ally is a catalyst, opening the door to have an even larger conversation with those institutions as to what needs to be addressed,” said Nicolaas Matthijs, product manager at Blackboard Ally. “The score that we’re seeing on the average is fairly low. But they didn’t know that until they had Ally.”

“Ally is a catalyst, opening the door to have an even larger conversation with those institutions as to what needs to be addressed,” said Nicolaas Matthijs, product manager at Blackboard Ally. “The score that we’re seeing on the average is fairly low. But they didn’t know that until they had Ally.”

When Blackboard last year conducted an anonymized survey of the accessibility factor of institutions' courses, the average accessibility score was 27 percent. That has since crept up to 30 percent.

“In the last five years, there’s been some progress. The bad news is the starting point is very poor,” Matthijs said. “Progress that has been made is fairly small. There’s a lot of work to be done.”

Blackboard doesn’t pretend that using Ally on its own is a workable solution. Ally can address “low-hanging fruit,” according to Matthijs, and point to areas where an institution’s disability services can intervene more closely, but it doesn't substitute for a human's watchful eye.

Canvas’s Jared Stein similarly describes the company’s Accessibility Checker as “a very human-centric, engaging tool that doesn’t eliminate the human interaction from the equation.”

Udoit, an open-source tool funded in part by Canvas, was born half a decade ago at Central Florida out of a similar desire to streamline accessibility conversations. The institution's Center for Distributed Learning and Student Accessibility Services secured a $10,000 grant from Instructure (Canvas's developer) to create the tool, which is now used by more than 50 institutions, according to Kelvin Thompson, the center's executive director. The tool analyzes announcements, assignments, discussions, files, pages, syllabi and module URLs. Items outside its purview include external documents and some video/audio files.

“It’s an arrow in the quiver; it’s a step in the right direction,” Thompson said of the tool.

What Tech Can (and Can’t) Do

From Blackboard’s perspective, “low-hanging fruit” includes identifying documents that have been scanned rather than originated online. Scanned documents are much more difficult to make accessible than digitally native content, because they don't lend themselves to screen readers.

But digital tools are likely to miss subtle details that can make a big difference. For instance, text or images in particular colors might pose a challenge to colorblind readers, but technology tools are unlikely to flag those as problematic. Technology might not have the firmest grasp on “Italian opera, organic chemistry” and other fields with jargon that tools might not seamlessly transcribe, Nemeroff said.

In some cases, technology is better suited to answering binary questions than to identifying more complex defects, according to Jared Smith, associate director of Web Accessibility in Mind (WebAIM), a Utah-based nonprofit that provides web-accessibility consulting to higher education institutions and other organizations. A tool can say whether an image has been outfitted with alternative text that blind readers can hear in place of seeing the image -- but it often can’t say whether alternative text is accurate, or whether it’s been installed automatically by the software program, Smith said.

Technology can determine whether a video has been outfitted with captions, but not whether those captions are more than “automatically generated gibberish,” Smith said. Drop-down menus are another source of confusion. Automated tools struggle to analyze those menus’ complex code, which can be problematic for users who operate the computer without a mouse.

Smith estimates that augmented tools identify a little more than a quarter of potential errors. “That means there’s another 70 percent that’s going to extend beyond the tools to identify,” Smith said.

Tech tools can be misleading in the opposite direction as well, Moore said. Some images, for instance, don’t require embedded alternative text for screen readers because they’re stock images that aren’t essential to understanding the written material, or because they're technically tables that function like text boxes. Observers of accessibility reports might get discouraged by seeing a large number of errors, but that number might be artificially high.

What More Is Needed?

Nemeroff at Dartmouth believes institutions have started to take a more active role in addressing accessibility for reasons that go beyond avoiding lawsuits. His team has started discussing accessibility with instructors throughout the design process.

“If you’re not doing this kind of broader strategic and operational planning to make sure these things are happening and that people are changing their behaviors, simply putting Ally out there isn’t going to change the underlying practices that are either promising or problematic entirely,” Nemeroff said.

Blackboard's work with institutions has followed a similar path, according to Matthijs.

“As we’ve started having these conversations with institutions, I’ve seen a noticeable trend -- that fear of litigation is less and less the starting point of the conversation, less and less becoming a driver,” Matthijs said. “Institutions are more and more starting -- it’s a slow evolution but noticeable -- to see some of the opportunities, and they’re now starting to see other institutions that are trying to tackle this problem.”

Companies are still grappling with the right balance between serving institutions and enabling them to tackle accessibility more effectively on their own. For its part, Canvas hopes to partner specialized tools and companies in an effort to tackle accessibility at a more granular level. Though the company is light on specifics, Stein believes it’s likely technology will within the next five years be much more capable of addressing accessibility questions than it is now.

“I think institutions are realizing more what the limitations of those tools are,” Stein said. “They’re not a plug-and-play solution, but it can be part of a broader accessibility effort.”