You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The Washington Post ran an interesting story last week on America’s trucker shortage. The trucking industry needs about 100,000 more drivers than it has. Despite good pay and benefits - new truck drivers can earn $70K with signing bonuses and health insurance - too few are training to become truckers. Retention is even more of an issue, with an annual turnover rate of 94%.

This trucker shortage is a supply driven problem. There is plenty of demand for truckers. There is an inadequate supply of people willing to train for and do the work of truck driving. Higher wages seem to have more of an effect of causing drivers to switch from one employer to another, rather than causing new drivers to get certified.

The reason for the supply shortage is that trucking is a difficult and dangerous jobs. Over the road truckers can be away from home for weeks at a time. Commercial driving is 8 times as deadly as working in law enforcement. Truckers reportedly experience high rates of illness, stress, and divorce.

My conversations with higher ed colleagues from across the country has caused me to become interested in understaffing. One constant across higher education seems to be that every college and university is trying to do more with fewer employees.

For those working in higher ed, employment feels increasingly tenuous and risky. For those wishing to get into higher education, the odds seem to be getting worse.

On the instructional side, we all know about the growth of adjunct, temporary, and contingent faculty in place of full-time tenure track lines.

On the staff side, we are increasingly seeing positions not being renewed when someone retires. New staff positions, if they are created, are often short-term roles.

The reason for the people shortages in higher ed are demand driven. There is a willing supply of people who would like to work in higher education. The demand for these workers - the willingness off colleges and universities to hire people - continues to decline.

The reason why colleges and universities are loath to hire, or to hire full-time and non-contingent faculty, is that labor costs account for 60 to 70 percent of total spending.

Spending on instructional faculty and staff accounts for about half of all labor costs.

Limiting the number and compensation of faculty and staff is one of the few ways that a college or university can constrain costs.

Cutting other areas of spending, such as deferring maintenance on buildings, can help balance budgets in the short-term. But those bills eventually come due. Lowering spending on marketing, recruitment, or tuition discounting is also very difficult for tuition-dependent institutions, as applicants and yields are sensitive to these spending levels.

I’m fascinated by how higher ed and trucking (and many other industries) have ended up, for opposite reasons, in the same place. Both supply (trucking) and demand (higher ed) shortages are causing acute and endemic levels of understaffing.

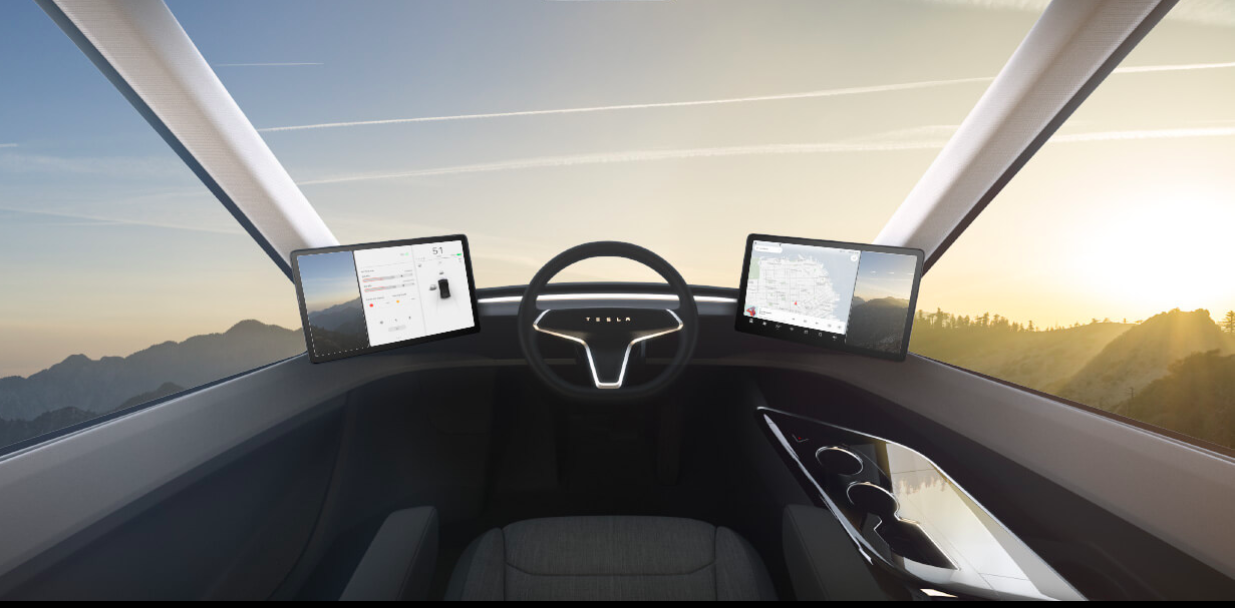

Will future technologies alleviate supply and demand driven employee shortages?