You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

It’s hard to think about the future of management education without thinking about the future of work. In case you haven’t noticed, there is no shortage of predictions about the future of work. Any reputable consulting firm has a report out on the future of work, including McKinsey, Bain & Company, BCG, Deloitte, and PwC. Think tanks, media outlets and other organizations also have thoughts on the future of work and how to prepare for the that future, including the World Economic Forum, Fast Company, Strategy+Business, the OECD, The European Political Strategy Centre, and Nature. MITx even has a course about it.

The upshot? For starters, it’s a good time to remember Peter Drucker’s quote: “The only thing we know about the future is that it is going to be different.” Indeed. Or, as the OECD puts it,

“What is certain is that the future is uncertain. . . What is important, however, is to build resilient and adaptable labour markets that allow workers and countries to manage the transition with the least possible disruption, while maximizing the potential benefits offered by the three mega-trends [globalization, technological progress, and demographic change.”

A New York Times article (which includes a great chart on the change in U.S. jobs between 1980 to 2012, showing that jobs requiring social skills are generally the jobs that grew) discusses how work is changing and the skills required for the future of work are also changing:

“Preschool classrooms . . .look a lot like the modern work world. Children move from art projects to science experiments to the playground in small groups, and their most important skills are sharing and negotiating with others. But that soon ends, replaced by lecture-style teaching of hard skills, with less peer interaction. Work, meanwhile, has become more like preschool.”

You can see David Deming’s paper, upon which much of the NYT article is based, here (this 2017 article is an update of the 2015 article) and an outline of the 2015 article here. Findings from World Economic Forum research concur with much of what Deming found:

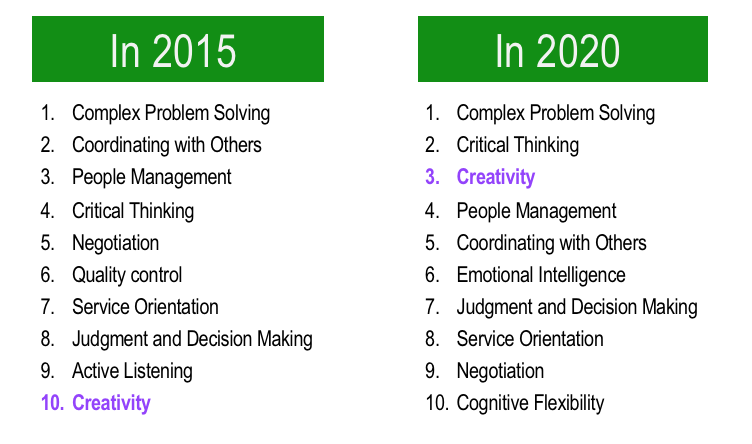

Top Ten Skills for Workplace Success: 2015 versus 2020

What’s a Business School to Do?

Many of these skills can and should be taught in management programs – and some schools are already doing a good job in these areas. But more can be done. As Tom Wujec mentions in a TED talk on a design challenge he runs with many different groups, “. . . among the worst [performing teams] are recent graduates of business school. . .And the reason is that business students are trained to find the single right plan. . . and then they execute on it.” He goes on to note that among the best teams are those that are recent graduates of kindergarten.

Business schools have faced a fair amount of criticism in the past, for everything from being responsible for causing the 2008 financial crisis through teaching the wrong things. The realization that business schools need to change isn’t new and, in fact, the indications are well captured in many different articles, books, and reports. Here are three that I find particularly relevant.

The first I found in the prologue to The Big Short, Michael Lewis’s book on the financial crisis of 2008:

“When I sat down to write my first book [Liar’s Poker], I had no great agenda, apart from telling what I took to be a remarkable tale. . . I hoped that some bright kid at Ohio State University who really wanted to be an oceanographer would read my book, spurn the offer from Goldman Sachs, and set out to sea. Somehow that message was mainly lost. Six months after Liar’s Poker was published, I was knee-deep in letters from students at Ohio State University who wanted to know if I had any other secrets to share about Wall Street. They’d read my book as a how-to manual.”

The second is in the book From Higher Aims to Hired Hands: The Social Transformation of American Business Schools and the Unfulfilled Promise of Management as a Profession. In the book, Rakesh Khurana notes the rise of economics and the quest for shareholder value and the devaluation of leadership and organizational studies. Here are a few quotes from the book:

“Inside business schools, economists on finance faculties used principal-agent theory to recast the role of management. Instead of being responsible to multiple stakeholders for the long-term well-being of the corporation, managers were now said to be responsible only to shareholders, a group whose composition changed continually and that was focused entirely on short-term gains. . . The resulting corporate oligarchy had no role-defined obligation other than to self-interest.” and

“The reality is that inside universities and research-based business schools, leadership has relatively low status.”

The third is from an Harvard Business School Working Knowledge article titled, “What Is the Future of MBA Education?”, which interviews David Garvin and Srikant Datar about their then-new book, Rethinking the MBA: Business Education at a Crossroads. In the article, Garvin notes:

“The common question we heard was about the value added of an MBA degree. In every interview, deans and executives returned repeatedly to that question, as well as to a large set of unmet needs that they identified in areas such as leadership development, skill at critical, creative, and integrative thinking, and understanding organizational realities. . . The single strongest theme we heard in our interviews was the need for MBA students to cultivate greater self-awareness. . . The second theme we heard was the need for practical skills: how to run a meeting, make a presentation, and give performance feedback. The third theme was the need for MBAs to develop a better sense of the realities of organizations within which leaders operate. Politics – issues of power, coalitions, and hidden agendas – are part of that reality. Yet MBAs, with their analytical focus, always try to find the ‘right’ answer. . . Executives and deans told us that MBAs need to develop cultural intelligence, specifically a better understanding of which practices, strategies, and behaviors are universal and which are contingent.”

And now applications are leveling off, and even dropping in the United States, one of the top markets for management education. According to GMAC research, “programs in Europe, Canada, India, and East and Southeast Asia gaining applications while many US programs see declining volumes from shifting demand among international applicants.” Add to this the fact that U.S. business schools are having a harder time attracting international students, and you get articles with titles such as, “Will the MBA Degree Become Less Valuable in the Near-Future?” and “Nothing Special: MBAs are no longer prized by employers.” The Economist article notes that “only 7% of graduates from India’s 5,500 business schools are employable upon graduation.”

So, what can we make of all this? Some of my thoughts on how we might prepare – both individually and collectively – for the future of work include:

- Refocus on learning as a lifelong endeavor. Average life expectancy is rising, more people are wanting (and often needing) to stay in the workforce until much later in life, and the skills they need for the various careers they’ll have will evolve over their lifespan. Colleges and universities need to think this through and create new programs, pathways, and platforms to reach learners at all stages of life.

- Understand that the way we create and deliver education through the university is quite likely to change. The higher education market is in the midst of unbundling. While this will create winners and losers in the higher education arena, it may be a good outcome for increasing access to higher education and spur innovation in higher education.

- Focus more on the human side of management. In his 1996 article, “The Human Side of Management,” Thomas Teal noted that “mediocre management is the norm” and that one reason for this is that “in educating and training managers, we focus too much on technical proficiency and too little on character. . . But we’re still in the Dark Ages when it comes to teaching people how to behave like great managers – somehow instilling in them capacities such as courage and integrity that can’t be taught. Perhaps as a consequence, we’ve developed a tendency to downplay the importance of the human element in managing.” Twenty years later, this still rings true. Poor management demoralizes people and ultimately takes a toll on performance. At a minimum, perhaps we should have everyone read Bob Sutton’s first book, on building a civilized workplace book, and his second one on surviving one that isn’t.

- Teach our children and students about the importance of ethical behavior (and enact policies that support this and laws that punish bad behavior). It matters and will help us shape a world – of work and otherwise – that we all want to live in.

What do you think?