You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Remember Lolo Jones?

Yeah, me neither, or me barely. For six or eight weeks prior to the London Olympics the 100-meter hurdler seemed ubiquitous, appearing in endorsements and on magazine covers, including being one of the athletes featured on Time magazine’s Olympics preview series.

She made herself open to the media, doing interviews, including one with Mary Carillo on Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel, where she talked about being a virgin at age 29 and wishing to remain so until marriage. She said that maintaining her virginity was more difficult than training for the Olympics

This disclosure significantly upped her Q Score as other media outlets had her on to repeat what she’d already said, as though they couldn’t believe their ears that an accomplished, well-spoken, beautiful woman featured on magazine covers was going to abstain from sex until marriage.

The backlash struck before she even had a chance to hit the track, with the New York Times’ Jeré Longman writing a bit of news commentary implying that this empress had no clothes, and not just when she was posing for the ESPN Magazine body issue. Noting that she had finished third in the American trials, and had only the 20th best time in her event this year, Longman declared that the attention Jones was receiving:

“was based not on achievement but on her exotic beauty and on a sad and cynical marketing campaign. Essentially, Jones has decided she will be whatever anyone wants her to be — vixen, virgin, victim — to draw attention to herself and the many products she endorses.”

Jones finished 4th in the Olympics, 1/10th of a second out of a bronze medal.

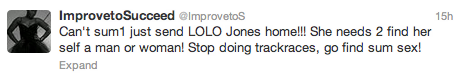

The Twitterverse was merciless in the wake of the race:

And so on…

In the eyes of the public, or at least the public with Twitter accounts, Lolo Jones was a loser on multiple fronts.

Following her 4th place finish, Lolo Jones made an appearance on the Today Show where she was asked about the backlash to her public profile, and the Times article in specific.

Jones said, “I just thought that that was crazy because I worked six days a week, every day, for four years for a 12-second race and the fact that they just tore me apart, it was just heartbreaking.”

--

The “Harvard Cheating Scandal” continues to deepen and darken. An anonymous student told Salon that the university is guilty of a kind of bait and switch, that in previous years, “Introduction to Congress” had been viewed as a kind of gut course.

As he told Salon, “That’s why people took the class in the past: fun lecture, goofy class, you go in and go out you know…. We took the class with the same assumption.”

But the actual exam, according to students talking to the New York Times, was “confusing” and designed to “trick” students.

The guidelines at the top of the test say that while the exam is open note, that collaboration and consultation with others is not allowed.

One of the accused students told Salon that Harvard is “out for blood” with their investigations, looking for scapegoats. Students are “lawyered up,” ready to fight over the “unfair process.”

There’s been a lot of commentary on this “scandal,” the most interesting of which may be from Howard Gardner, an education professor at Harvard, who literally wrote the book on the balance of excellence and ethics.

Gardner has been at Harvard for just about his entire adult life, transitioning from one-time student to longtime professor, and through his work and research he has become worried about what he sees a “hollowness at the core” of his students. He reports that while the students he talks to say they are interested in good and meaningful work, (work that betters society and brings them personal fulfillment) mostly what they wanted, was to be “successful,” and in their eyes, being successful sometimes necessitates taking an ethical shortcut or two or three.

In Gardner’s words, “They feared that their peers were cutting corners and that if they themselves behaved ethically, they would be bested.”

In the world of these Harvard students, success has a clear scoreboard, one with a dollar sign in front of it.

--

I will admit to experiencing a bit of schadenfreude at both Jones’s failure to medal and the Harvard cheating scandal stories. (Much more in the case of Harvard.) Prior to the games, Jones really did seem like an attention hog, attention that was possibly coming at the expense of her superior hurdling countrywomen, Dawn Harper and Kellie Wells.

But then I watched that Today Show interview where she talked about her heartbreak and how hard she had worked to return to the Olympics following taking a spill in the same event at the Beijing games, even as she looked like a certain victor, and I felt the shame start to creep through me.

I tell myself and my students daily that what matters is the journey, not the destination, that we need to be focused on doing the work, rather than the grade at the end of that process, and here I was, in my head, declaring the 4th fastest women’s hurdler in the world a loser.

Lolo Jones knows more about hard work and sacrifice than I’ll ever approach. She has lived a life of obvious integrity, consistent with her values. She has worked hard, and been rewarded for her hard work, for example, improving her time between the U.S. trials and the Olympics by 2/10th’s of a second. She just wasn’t rewarded with an Olympic medal.

My schadenfreude in the case of Harvard was wrapped up in envy over how “man’s greatest university” viewed, and my belief that Harvard is indeed not so special as it’s made out to be (not particularly different from any other selective university), that it too has gut courses and lazy professors and cheating students.

When I talk to my students about the Harvard story and tell them that it was a class with more than 200 students with a take-home exam, they essentially ask “what did they expect?” Of course they’re going to cheat. They not only made it possible; they made it desirable.

At Jezebel, Lindy West offers a defense of certain kinds of cheating:

When I was in high school and time was crunched, my friends and I took turns passing around our math worksheets, because math worksheets were—to a certain extent—bullshit. But I would never have cheated on a test or bought a term paper online. Some forms of "cheating" are actually more akin to savvy time management—it can be just a disparaging term for "efficiency." Some cheating is about determining which bullshit counts and which doesn't, and then cutting out the bullshit bullshit. A lot of school is bullshit. And I feel like a big part of a high school and college education is learning how to navigate around bullshit. Because it's bullshit. You know?

West says that independent of whether or not something can be viewed as “cheating,” “Identifying shortcuts and successfully taking them is useful.”

I imagine that many of the Harvard students thought that the test was, on some level, “bullshit,” and they may even be right. Granted, I know very little of the specifics, but a multi-hundred person course on introducing students to Congress doesn’t sound Harvard-worthy to me.

Howard Gardner is concerned about what the cheating scandal may do to Harvard, how it may harm people associated with the university through no fault of their own.

But he is more worried about what we’re signaling to our students, about how they do see “professors cut corners -- in their class attendance, their attention to student work and, most flagrantly, their use of others to do research.”

This is where these two stories -- Harvard and Lolo Jones -- intersect for me, those signals that Professor Gardner is talking about because it makes me realize that in the end, we are what we admire.

Prior to the Olympics Lolo Jones was “admirable” because she was a successful athlete and hot looking and willing to pose provocatively for magazines. That looks a lot like success by today’s standards. (Beauty, money, fame.) The declaration of her virginity made some see her as a bit of an outlier (à la Tim Tebow), but still admirable. Missing out on something, but admirable for her sacrifice.

After her race, Lolo Jones was a loser to be pitied, not admired, mocked 140 characters at a time, rather than celebrated.

A student at Harvard who gets a B on that exam because they worked independently as instructed would likely be viewed as a bit of a sucker by classmates who combined forces and collaborated. That person is dumb for not “identifying shortcuts.” They are putting up barriers to their own “success.” The students at Harvard, and indeed across the country know well what matters, how they are being measured. For now it is grades, grades that will lead to financial security, and if they’re either lucky, or find enough shortcuts, incalculable wealth.

Howard Gardner says he hopes that the scandal will have a, “positive outcome if leaders begin a searching examination of the messages being conveyed to our precious young people and then do whatever it takes to make those messages ones that lead to lives genuinely worthy of admiration.”

I wonder how this is possible in the face of the prevailing culture. I’m interested in ideas from others.

I don’t know about Professor Gardner, but I worry that we’ve already lost that battle, and maybe the whole damn war.

--

John Warner frequently displays mercy on Twitter @biblioracle.