You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

I've been hard on assessment in this space, but when I saw David Eubanks of Furman University speak at the Disquantified conference I was buoyed by hearing an assessment expert who shared many of my frustrations, but also could articulate a way out of what seemed to be an unproductive cycle. In this post he lays out a different way of measuring institutions which values the work of the faculty of students, rather than feeding the meaningless assessment machine. - JW

--

Reclaiming Assessment's Promise: New Guidance from the Department of Education Could Help

By David Eubanks

“The assessment of student learning in higher education has been headed down an unproductive path for too long. Not enough faculty and administrators engage in an assessment process that fosters cognitive and affective learning for all their students.”

Those are the first two sentences of a March, 2019 article written by representatives of the three main assessment organizations (AACU, AALHE, and NILOA). Last April, one of the authors was reported as calling for moving beyond “assessment as bureaucratic machine.”

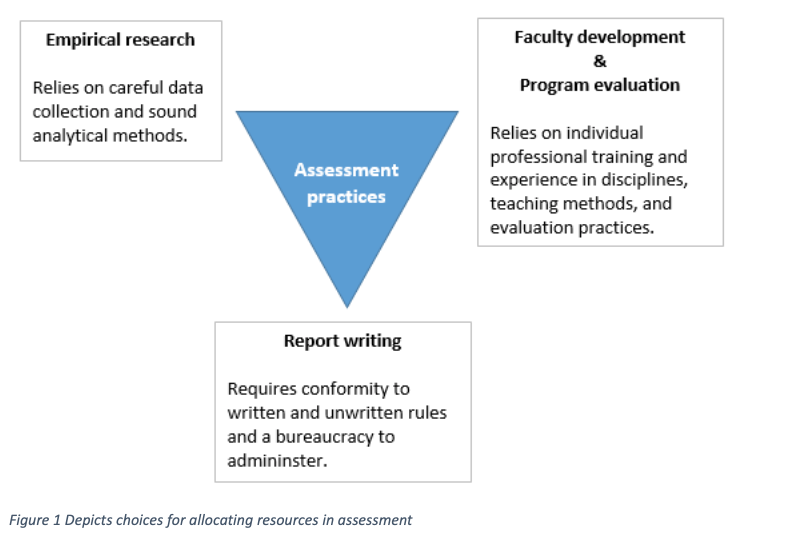

While this feels like progress toward more meaningful practice, my own experience illustrates how difficult it is to disentangle useful assessment work from rote box-checking. You can think of assessment work as an upside-down triangle, with empirical research and faculty/program development at the top two corners and report-writing at the bottom. Assessment offices allocate their resources somewhere in that triangle, with varying emphasis on the three goals. Currently, a large fraction of activity is at the bottom of the triangle: organizing report-writing in order to satisfy external peer reviewers.

The report-writing drill varies by region and type of institution, but it’s probably something like this: gather some senior papers, regrade them using an approved rubric, then average the numbers and compare to some approved benchmark for success in alignment with published goals. If the results don’t measure up, then you are supposed to imagine a fix. This is often a nominal remedy like “we will add more problems on complex thinking to the syllabus.” This work must be thoroughly documented in the proper format.

---

I was too credulous in 2000 when I transformed from a math professor to a director of assessment activities. I spent several years following the practices advocated by assessment experts and built a bureaucratic machine, with its committees and report templates and due dates.

The elements looked for in peer review—goal statements, description of assessment methods, and so forth—can be spotted in the Department of Education’s guidelines for accreditors, regarding student learning (excerpted from here):

[A]ccreditors are able to demonstrate that they have criteria/processes for evaluating the institutional assessment/improvement activity, such as criteria for evaluating the objectives/goals established by the institution; for assessing the data collection activities and improvement plans; and for assessing the outcomes resulting from implementation of the improvement plans (pg. 32)

There’s nothing wrong with this guidance, but it got turned into a list of checkboxes that people like me became responsible for. Instead of taking a cautious approach to the complexity of understanding student learning, peer review culture ignored all those complications, assumed it was an easily-solved problem, and turned it into a formula.

After a while, I realized that my own assessment machine was a smog-belching monster that consumed more energy than it produced, but I assumed that I was just doing something wrong.Presenters at conference sessions bragged about their engines of knowledge and the rewards of positive peer review. These sessions usually address how to set up committees, format reports, and other machine-maintenance tasks. They and the software vendors all promise dramatic insights by “rolling up data” and “finding gaps.” The ongoing failure to fulfill that promise is often blamed on faculty.

It’s embarrassing to admit how long it took me to figure out something was wrong. By then I had written hundreds of blog posts on the subject as well as book chapters and journal articles. I had become involved as a peer reviewer and a board member of AALHE. I led workshops called “What to expect when you’re assessing.”

As I said, I was too credulous. I assumed that someone had done their homework and tested the assertions that consultants and conference-presenters kept making. I assumed that the peer-review standards had been validated with real results. Instead, it seems that those ideas were born of good intentions, and the results were (ironically) not critically examined. It is the fear of peer review that enforces conformity in much of assessment practice, not soundness of methods or usefulness of results. Most of all the regrading of papers with rubrics isn’t measurement and can’t be used for “finding gaps” or “rolling up” to see if institutional goals were met—there is too little data, it is of poor quality, and the models and methods used are too elementary to work. The assessment machine is comparable to mining Bitcoins: spending a lot of energy to find random numbers that are valued only by true believers.

For me, the weight of contradiction became so great that I began to work backwards, to first figure out what kinds of data-gathering and analysis are likely to generate usable results: reallocating our efforts up the assessment triangle. It became clear that the peer-review version of assessment is almost perfectly designed to fail as data-generating exercises. If you sat down to “backwards design” a plan to waste enormous amounts of time and money, you could hardly do better than the assessment report-writing machine that we have now.

---

Three things are clear: (1) data science is a powerful solvent for complex problems, (2) we need answers to complex questions about the quality and value of education, and (3) bureaucracy is no substitute for empiricism. When your car breaks, do you call the DMV or the mechanic?

Imagine if instead of spending the last twenty years doing crypto-measurement to perfect a report-writing culture, we had used that effort to understand how students succeed: their hopes when they attend college, the effect of their history on chances for success, what causes them to choose a major, how the individual traits of students can lead to individualized pathways, what course grades and course evaluations mean and how to improve them, and so on. What if we had used empirical methods instead of relying on a rigid set of rules about what can and cannot be done (like: you can’t use grades or surveys as primary evidence).

Higher education needs good information both for improving services and for making the case to the public that college is worth the cost. As political and demographic changes continue to pressure colleges to adapt, the effective use of data will be ever more important. Institutions need the freedom to allocate assessment resources “up the triangle.”

The Department of Education recently weighed in on this topic. They rewrote the handbook for accreditors encourage more freedom in meeting student achievement standards (pg. 9):

These standards may include quantitative or qualitative measures, or both. They may rely on surveys or other methods for evaluating qualitative outcomes, including but not limited to student satisfaction surveys, alumni satisfaction surveys, or employer satisfaction surveys.

This new language is important because it challenges two of the report-writing machine’s rules, viz: that course grades don’t measure learning, and that survey data (“indirect assessment”) isn’t useful on its own.

More explicit language telling peer reviewers to back off can be found in the proposed rules for accreditors:

Assessment models that employ the use of complicated rubrics and expensive tracking and reporting software further add to the cost of accreditation. The Department does not maintain that assessment regimes should be so highly prescriptive or technical that institutions or programs should feel required to hire outside consultants to maintain accreditation. Rather than a “one-size-fits-all” method for review, the Department maintains that peer reviewers should be more open to evaluating the materials an institution or program presents and considering them in the context of the institution’s mission, students served, and resources available. (Section 602.17b, pg. 104)

In other words, scrap the machine.

Some examples from our work at Furman University illustrate the usefulness of ignoring the report-writing culture. Our weekly assessment meeting is not about reports, it’s about data and research. Here are some recent findings from grades and survey data:

- Student self-appraisal of their abilities has long-term effects on choice of major and career after graduation, sometimes unnecessarily limiting their options.

- Early academic performance is a predictor of many outcomes; high school grades predict the trajectory of writing improvement over four years of college (see my recent article in Assessment Update). It also predicts affinity for the university at graduation.

- Self-reported impact of experiential learning is very informative, for example in quantifying the value of internships (high) in comparison to work study (low). This leads us to improve work study experiences to make them more impactful.

- The overlapping effects of parental income and education on student choices and outcomes are complicated, e.g. education is more important to on-time graduation than money is.

- There are quantifiable links between internships/research and early career/graduate school transitions, and these career tracks can be predicted early by attitudes and sense of purpose.

- On course evaluations, students can accurately assess how difficult a course was, but their ratings of teaching quality are unrelated to difficulty—the strongest biases are in favor of elective courses.

- There are significant differences between academic areas with respect to grade reliability. Reliability of first year grades is particularly important (see this article for more on reliability).

All of these bullet points are subject to cautions and error bounds, and the findings are probably are not generalizable to your institution, although the methods probably are.

There are too many important questions to waste time on poor methods, like those unfortunately now ossified in assessment’s report-writing culture. There is now a glimmer of hope that we can change that.

Accreditation by peer review is itself not the problem. After years of participating in the review process myself, the assessment standards stick out as an oddity—the one place where adjudication is not aligned with the advertised purpose of the standard, and where there are unofficial gotchas. Scrapping the machine entails changing the assessment peer review culture to adopt different values. That will be difficult to do, but it must be done. There are a lot of talented people in assessment and institutional research offices around the country. Let’s stop forcing them to be bureaucrats and let them start on the list of questions we really need answers to.

--

David Eubanks is Assistant Vice President for Institutional Effectiveness at Furman University, where he works with faculty and administrators on internal research projects. He holds a PhD in mathematics from Southern Illinois University, and has served variously as a faculty member and administrator at four private colleges, starting in 1991. Research interests include the reliability of measurement and causal inference from nominal data. He writes sci-fi novels in his spare time.