You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

There is no more humbling experience in my life as a writer than reviewing the copyeditor’s work on a book manuscript.

I almost said “humiliating” instead of humbling, but I’m trying to be kinder to myself, especially in the wake of spending a week in the presence of my errors. I like to think I have some strengths as a writer, but the final polishing of my own work is not one of them. It’s not that the work is sloppy or careless, but when confronted with it, I cannot turn off my engagement with the ideas I’m wrestling with long enough to focus down to the grittiest nits.

Fortunately, when it comes to producing a book you get to work with a professional with a very specific set of skills, skills acquired over a very long career. Skills that save people like me from the nightmare of sending a book into the world with errors which could have been caught.

My expert is named David Goehring, and like every other copyediting I’ve experienced, I am astounded by the care and precision he brings to the task. It is not merely a matter of knowing grammar and usage and how to properly format a manuscript. A good copyeditor is required to do the same thing I am attempting in the drafting of the book, consider the ideas and their potential impact on the audience. The difference for the copyeditor is the ideas belong to someone else, which requires a simultaneous act of interpretation of the author’s message while also keeping the audience always in sight.

This is decidedly not easy, both because the original author’s ideas may not be 100% clear (particularly in a drafting stage), and the copyeditor may not be fully simpatico with the audience.

But every book I’ve ever done, invariably a copyeditor has zeroed in on the things I wasn’t sure about as I was writing, questionable inferences, arguments which I’m hoping work, but suspect may not, references which tickle me, but may confuse audiences.[1]

The first job I applied for after college was as an entry-level copyeditor for a textbook publisher in Champaign, IL. They handed me a screening test of thirty sentences which I was tasked to correct (if they needed correction), utilizing standard copyediting notation.

I walked out before even completing it, realizing I was in over my head. I now recognize that I may have been hasty, that there may have been an opportunity for training, but even so, I think I knew I did not have what it took to do the job as well as it must be done.

I’m a much better polisher of other people’s work, and I am a better developmental and line editor above that. This divide between how I can see the work of others versus how I see my own work has influenced how I respond to my students’ work.

Just about any of us has looked at a piece of student writing and wondered how or why they made a particular mistake. For a long time, I viewed students through their defects, focusing on the error itself, as opposed to the root of that error, or even better, to see the student writing as a whole, reflective of the person who wrote it, warts and all.

Much of this was wrapped up in the teaching folklore I’d absorbed and was perpetuating. I was doing unto others what had been done unto me. But some of this was also rooted in how I viewed my own defects as a once unpromising student (as measured by grades) myself. I knew that I probably could’ve worked “harder,” and so assumed my students’ mistakes were rooted in similar shortcomings.

But over the years, having worked as teacher, writer, editor, I’ve come to a much greater appreciation for the complexities of all parts of the writing process and the inevitable ways an individual working alone will fall short. In class, I started to mitigate against this by creating working groups of students who would fulfill different roles for each other during a project, sometimes editing, sometimes proofreading. I’d even occasionally add in a “cheerleader,” someone whose task was to explicitly highlight the positives.

The goal was to expand the range of responses to the students’ writing in order to help the students reconceive and then revise their own work. All writers make mistakes. The gap between our intentions and the results is never fully bridgeable. Recognizing this is the an important step to developing as a writer.

Sometimes we need help. I’m grateful to be in a position where it’s available to me.

Copyediting is also a fraught time because it’s really my last chance to fix anything I’ve gotten wrong. At the same time, it’s exciting because I believe I’ve gotten many things right, but there’s still many months until others have a chance to read it.

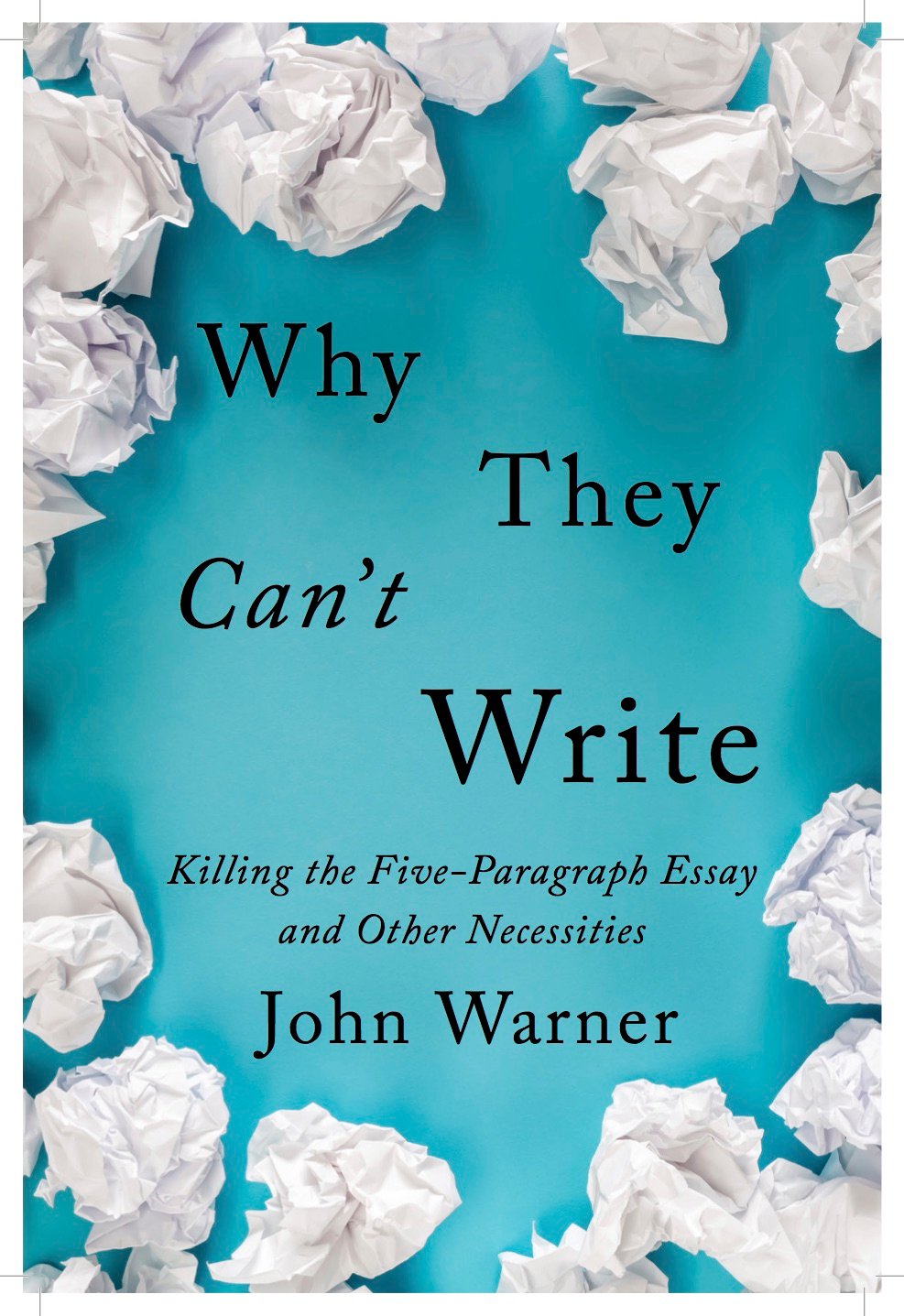

Here’s the cover. It’ll be published this December.

[1] For example, the third paragraph of this post is an extended reference to a famous monologue delivered by Liam Neeson in the movie Taken. The sentiment of the paragraph is something I wholeheartedly believe, but framing it through Taken is mostly just entertaining for me and a very small handful of readers who may get the reference. A good copyeditor may offer a caution if my fun is obscuring my point. The copyeditor on this project has saved me from myself several times. With the blog, though, I'm left to my own instincts, for better or worse.