You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

In an undergrad class we recently finished a unit on three Heart of Darkness texts: the novella itself; the film Apocalypse Now; and Hearts of Darkness, the documentary made, in part, from footage shot by Eleanor Coppola as her husband struggled to finish Apocalypse. The interest is in how the book and films talk to each other, and what they have to say to our time.

There are surface similarities among the three, of course: plot (a voyage to witness or confront a guy supposedly gone mad with power), setting (up rivers in the jungles of Africa, Southeast Asia, or the Philippines), and characters (a Kurtzean figure, a Marlovian role, and similar supporting players, such as the shadowy figures who stay behind and wield the true power—in the novella, company men in Brussels; in Apocalypse, the brass and spooks in Saigon who task Captain Willard [Martin Sheen] with assassination; and in Hearts, studio execs and money men in Hollywood).

More importantly, all three texts are meditations on facing up to, variously, “the horror,” the “abyss,” or “the barren darkness of [the] heart” of the human animal. For Conrad, human nature is often like the landscape: immutable, mute, mysterious, gloomy, brooding, lurking, inscrutable, hazy, incomprehensible, but, above all, dark. HoD and Apocalypse both imply a genocidal instinct underpinning the “civilized” West—I think of Christopher Browning’s “unequal or asymmetrical embrace of the Enlightenment”—and show how colonialism provides it a stage, whether in the “merry dance of death and trade” or in foreign wars.

Even in Hearts, which is primarily an extended metaphor of the artist and artistic process, production designer Dean Tavouris speaks uneasily about hiring hundreds of Filipino locals to do hard, dangerous labor for a dollar or two a day, simply because they were cheap, unlike Hollywood teamsters. He hopes they weren’t being taken advantage of, he says, “but that’s what they were paid.”

There are also corresponding targets in all three texts for Chinua Achebe’s accusation that Conrad displays a “preposterous and perverse arrogance...reducing Africa to the role of props for the break-up of one petty European mind.” The same might be said for both Francis’ and Eleanor’s work. (She shares directing credit for Hearts with Fax Bahr and George Hickenlooper.)

“A film director is kind of one of the last truly dictatorial posts left in a world getting more and more democratic,” Coppola says in Hearts. Later: "My film [Apocalypse] is not about Vietnam. It is Vietnam,” he says in grotesque overstatement. “It's what it was really like. ... There were too many of us. We had access to too much money. Too much equipment. And little by little we went insane." The communist rebellion in the Philippines, the miseries of Typhoon Olga, and Martin Sheen’s heart attack become props to his own financial risks, production difficulties, and suicidal thoughts.

Since we’re not famous film directors or Special Forces colonels, it’s sometimes difficult for students to accept the texts’ warning that we all may contain the seeds of darkness. Students certainly know they mean no one like them harm; they’ve been raised in families and the church; have been good sports on the field; love America; are ambitious but haven’t even had a chance to exert their wills yet. If the stories are trying to suggest some slant of original sin, well, what’s a Sunday school for?

HoD has its answer. When Marlow visits his aunt, who got him his job in Africa, he is angry at her willful unconsciousness. “There had been a lot of...rot let loose in print and talk just about that time, and the excellent woman, living right in the rush of all that humbug, got carried off her feet. She talked about ‘weaning those ignorant millions from their horrid ways,’ till, upon my word, she made me quite uncomfortable. I ventured to hint that the Company was run for profit.”

Not looking, due to filters of piety, patriotism, or pollyannaism, does not absolve. More than once, telling his story, Marlow has an outburst about the insulated lives of his listening friends.

“Here you all are, each moored with two good addresses, like a hulk with two anchors, a butcher round one corner, a policeman round another, excellent appetites, and temperature normal—you hear—normal from year’s end to year’s end. [...] You can’t understand. How could you?—with solid pavement under your feet, surrounded by kind neighbours ready to cheer you or to fall on you, stepping delicately between the butcher and the policeman, in the holy terror of scandal and gallows and lunatic asylums.... Of course you may be too much of a fool to go wrong—too dull even to know you are being assaulted by the powers of darkness.”

“Try to be civil, Marlow” one of them growls eventually.

What “civil” might mean is, of course, in question. “Never get out of the boat,” Captain Willard (Apocalypse’s Marlow) intones—the boat meaning the thing you’re familiar with. “Absolutely goddamn right. Unless you were going all the way.”

What “civil” might mean is, of course, in question. “Never get out of the boat,” Captain Willard (Apocalypse’s Marlow) intones—the boat meaning the thing you’re familiar with. “Absolutely goddamn right. Unless you were going all the way.”

And that’s one of the central problems of Kurtz: He does go all the way. His society/company sends him up, armed with money, equipment, and the freedom to exercise his power. He’s believed to be one of the best and brightest the society has produced (true of Mr. Kurtz, Colonel Kurtz, and Coppola). He is an extension of its values, its emissary, and it’s assumed he’ll be made the head of the enterprise one day. And for a time (while he can still make others rich or otherwise powerful) he’s lauded as a great man, a writer, an artist, a musician, and a commanding speaker.

But when you get off the boat of your own society, with its familiarity and protections, problems arise, not the least because now you’re messing with someone else’s society. Kurtz’s output drops—“unavoidable delays—nine months—no news—strange rumours”—and when he’s judged ineffectual, he’s removed from office, even sacrificed, to assuage the fake shock of the hypocritical society, which will pretend that going all the way was a bad idea to begin with. But of course Mr. Kurtz puts the heads of his enemies on pikes around his house; of course he turns their faces inward, so he can look at them, instead of turning them outward a a warning. He’s the id of the society that sent him, and he takes their mission to its illogical conclusion. Only afterward, when his utility is over, are his methods judged “unsound,” an embarrassment to the cause.

Much about the reputation of Kurtz has been inflated all along, Marlow discovers. His painting is creepy; a journalist says he “really couldn’t write a bit”; his fiancee’s people don’t think he’s good enough for her. “I had taken him for a painter who wrote for the papers, or else for a journalist who could paint—but even [Kurtz’s] cousin...could not tell me what he had been—exactly,” Marlow says.

What people seem to remember was not his accomplishments or his words, but the manner of his speech. Even Marlow says it to the last: “Kurtz discoursed. A voice! a voice!” The journalist, Marlow says, “informed me Kurtz’s proper sphere ought to have been politics ‘on the popular side.’ ...’heavens! how that man could talk. He electrified large meetings. He had faith—don’t you see?—he had the faith. He could get himself to believe anything—anything. He would have been a splendid leader of an extreme party.’ ‘What party?’ I asked. ‘Any party,’ answered the other. ‘He was an—an—extremist.’ Did I not think so? I assented.”

Kurtz was a demagogue in the making. That’s exactly why the company/society chose to elevate him. But even the fungus finds its limits, and while Kurtz’s power is deadly, it’s only as deep as the pockets his company can reach into. (Brando-Kurtz: “It’s our time to grab.”)

Conrad purposely keeps Kurtz’s words vague, so we’re thrust into the position of those who can’t seem to explain his substance. Coppola can’t do that on film, so there’s this monologue that Brando-Kurtz delivers:

“Horror and moral terror are your friends. If they are not, then they are enemies to be feared. They are truly enemies! I remember when I was with Special Forces... seems a thousand centuries ago. We went into a camp to inoculate some children. We left the camp after we had inoculated the children for polio, and this old man came running after us and he was crying. He couldn't see. We went back there, and they had come and hacked off every inoculated arm. There they were in a pile. A pile of little arms. And I remember... I... I... I cried, I wept like some grandmother. I wanted to tear my teeth out; I didn't know what I wanted to do! And I want to remember it. I never want to forget it... I never want to forget. And then I realized... like I was shot... like I was shot with a diamond... a diamond bullet right through my forehead. And I thought, my God... the genius of that! The genius! The will to do that! Perfect, genuine, complete, crystalline, pure. And then I realized they were stronger than we, because they could stand that these were not monsters, these were men... trained cadres. These men who fought with their hearts, who had families, who had children, who were filled with love... but they had the strength... the strength... to do that. If I had ten divisions of those men, our troubles here would be over very quickly. You have to have men who are moral... and at the same time who are able to utilize their primordial instincts to kill without feeling... without passion... without judgment... without judgment! Because it's judgment that defeats us.”

The monologue gets at something important. If war is a moral grotesquerie, then Coppola gives us a chance to be hoisted on our own petard when we protest how it’s prosecuted. How different is Kurtz’s admiration from that of the former helicopter crew chief who told me that RoK (Republic of Korea) troops that he ferried on SF missions in Vietnam came on board reeking of dried blood, rotten teeth, and kimchi, and that those hard men never took prisoners? Or my first First Sergeant in the army, with the Big Red One combat patch, who used to laugh that their unit motto in Vietnam was “women and children first”? The figure of Kurtz is a martyr to the discomfort of being shown the actions in which your civil society is complicit.

The endpoint of this sort of madness is always the same, and here too Kurtz can be counted on to come out with it, at the end of Marlow's summary: “It was very simple, and at the end of that moving appeal to every altruistic sentiment it blazed at you, luminous and terrifying, like a flash of lightning in a serene sky: ‘Exterminate all the brutes!’”

***

Later in the semester we’ll read Hiroshima and look at the ongoing debate, even among historians, whether the atomic bombings of Japan by the US government were necessary to end the war, and why so many civilians had to be targeted. The book has more urgency than usual, due to Trump’s game with North Korea. If the North Koreans launch missiles to splash down near Guam as threatened; if one of their rockets fizzles and lands on the Japanese mainland; if they detonate an atomic warhead in the open Pacific or explode one in space and take out satellites...will our president kill millions in North Korea? To start something and not “go all the way” might be to ensure the deaths of those “on our side,” after all. “[M]ilitary analysts believe that such a conflict would claim more than a million lives in South Korea in its opening phase, while also exposing American cities to the possibility of a nuclear attack.”

We are the society that put this president in office. Whether we like it or not, he is an extension of some aspect of American feeling and thought. He was touted by the money men and Republican pilgrims as an emissary of change, of advancement. In fact he is not only not our best and brightest, his only talents seem to lie in the manner of his speaking and his savage ruthlessness. “[H]e was hollow at the core,” Marlow says of Kurtz.

We have given Trump money, power, equipment, and the legal distance to exert his will. What will he do in his near-isolation? What in us will he enact?

In his “Rocket Man” speech at the UN last week, Trump threatened to “totally destroy North Korea. He asked, “Are we still patriots? Do we love our nations enough to protect their sovereignty and take ownership of their futures?”

It’s the notion of love in a dark heart that worries.

***

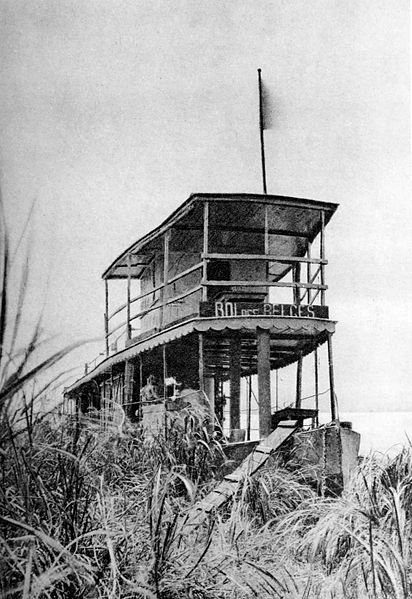

Photo: Purportedly the Roi Des Belges, the steamboat that Joseph Conrad piloted up the Congo. It was named for King Leopold II, whose Congo Free State killed as many as 10 million Africans. The boat provided the model for the “two-penny-half-penny river-steamboat with a penny whistle” that Marlow commands in Heart of Darkness and is a symbol of what he sarcastically calls “the cause of progress.” Wikimedia Commons.