You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

In early November 2016 I drove from Lake Charles, Louisiana, where we live now, to the Houston airport, to pick up New York City street photographer Donato DiCamillo. There wasn’t time to park in a garage, so I sat in a line of cars under a massive concrete building, regretting the giant cup of Diet Coke. I wasn’t sure I could identify Donato in a crowd, and he had no idea what I looked like. A couple of likely suspects came out of Arrivals and made eye contact, and I rolled down the window and yelled at one of them, “Hey! Donato!” I’ve hosted many campus visitors, and the minutes of first meeting are always awkward and exciting. “Donato!” He didn’t respond. We had a two-hour drive back. “Donato! My man! Hey!” The guy looked at his phone, embarrassed for me, and got in a different car.

Donato emerged after a time, muscular, tattooed, looking a lot like Henry Rollins in the ‘90s. He lightly carried a shoulder bag, a suitcase, and a Pelican case covered with stickers out to where I waited in the car. I raised the hatch, but he paused at the curb to check over the case’s contents: three digital rangefinder Leicas and a digital SLR Olympus, multiple lenses, a Japanese 6x6 viewfinder camera, a GoPro with its own case and mounts, chargers, cords, extra batteries, memory cards, and film. He hadn’t known what he might need, since he didn’t know exactly what he’d be shooting. Neither did I. As we got in the car he told a story about the flight attendant in New York insisting he surrender his professional equipment so they could stow it in the hold, and him resisting, and how the pilot came out of the cockpit and personally put it in a locker in the cabin with a measure of respect.

Donato emerged after a time, muscular, tattooed, looking a lot like Henry Rollins in the ‘90s. He lightly carried a shoulder bag, a suitcase, and a Pelican case covered with stickers out to where I waited in the car. I raised the hatch, but he paused at the curb to check over the case’s contents: three digital rangefinder Leicas and a digital SLR Olympus, multiple lenses, a Japanese 6x6 viewfinder camera, a GoPro with its own case and mounts, chargers, cords, extra batteries, memory cards, and film. He hadn’t known what he might need, since he didn’t know exactly what he’d be shooting. Neither did I. As we got in the car he told a story about the flight attendant in New York insisting he surrender his professional equipment so they could stow it in the hold, and him resisting, and how the pilot came out of the cockpit and personally put it in a locker in the cabin with a measure of respect.

I knew his gear cost more than my new car, and some of it was on loan from Leica, but more to the point, it obviously represented the future. Donato is fiercely ambitious and eager to make up lost time, and while the tools of his trade are necessary, they more importantly allow for process, and artistic process is his chosen life now.

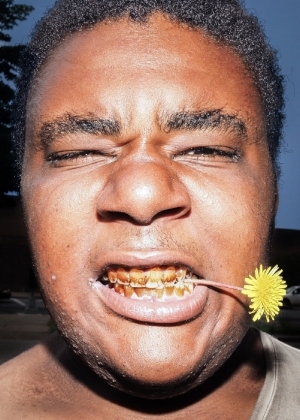

I’d learned of him a couple of months earlier, from a piece in the Huffington Post. He was just getting noticed by national media. I scrolled down through his portraits of Coney Island beachgoers and city dwellers, and his astonishing work reminded me of Diane Arbus and William Klein. There’s something deeply affecting in it. He has a deep compassion for his subjects, a great sense of humor, and, though he’s only been shooting a few years, sureness and an identifiable style.

I’d learned of him a couple of months earlier, from a piece in the Huffington Post. He was just getting noticed by national media. I scrolled down through his portraits of Coney Island beachgoers and city dwellers, and his astonishing work reminded me of Diane Arbus and William Klein. There’s something deeply affecting in it. He has a deep compassion for his subjects, a great sense of humor, and, though he’s only been shooting a few years, sureness and an identifiable style.

He shows us, I think, glory in the profane, and if I was a photo editor at The Atlantic, the New Yorker, Esquire, Tin House, Rolling Stone, etc., I’d throw him the few thousand bucks it would take to send him around the world, just to see what would happen. I think what would happen would be magic.

He shows us, I think, glory in the profane, and if I was a photo editor at The Atlantic, the New Yorker, Esquire, Tin House, Rolling Stone, etc., I’d throw him the few thousand bucks it would take to send him around the world, just to see what would happen. I think what would happen would be magic.

As it was, I knew I’d need to move fast. I explained by phone that if he didn’t mind not flying directly to Lake Charles, and if I paid some of the expenses myself, the McNeese Review, a print annual for which I’m the Editor, could bring him down to shoot during the week of the Presidential election. He asked half-a-dozen times how long we’d have to be in the car from Houston—he obviously had a thing about confined spaces, or boredom, or chitchat, or carbon footprints, or something—but he agreed. I couldn’t believe my luck.

I made a list of three- or four-dozen possible locations in and around Lake Charles, as well as on the Gulf, 30 miles away, and up the coast. Because the pages of the Review are small enough that panoramas and landscapes wouldn’t print well, and because Donato usually gets close to his subjects, I began to think of this as a sort of “Faces of Lake Charles” assignment. (The photos shown here are mostly outtakes from his visit.) I hoped he might capture something of interest at this odd time in our history, though the election itself probably wouldn’t be the focus. Donato had stressed to me from our first conversation that he’s not the kind of photographer to “cover things,” and besides, I couldn’t know what would happen that week.

There are tensions. Louisiana has turned red, of course, a relatively recent change. Trump won 58% of the state's popular vote, and there are many fringe elements for him to court and please. ("Thank you President Trump for your honesty & courage to tell the truth about #Charlottesville & condemn the leftist terrorists in BLM/Antifa," Louisiana's David Duke, former grand dragon of the Klan, tweeted after Trump called some of his friends "very fine people.") Lake Charles is now majority black, but the Klan recruited here recently, and the Confederacy is widely admired, with a Rebel statue on the courthouse lawn and lost-cause flags at all parades and gun shows. The state has some of the laxest gun laws, with open carry, no background checks, and no licensing required for buyer or dealer, and the highest number of gun deaths per capita in the country. Almost a quarter of Lake Charles lives under the poverty line, despite a petroleum economy that’s said to reward the community for its presence; 68% of the poor are black, in contrast to 26% of whites. And while there are many interracial families, there’s also a certain segregation I haven’t experienced elsewhere, even in caste cities like Miami. People have things to say but don’t say them, at least in public, or at least to people they believe are different from them in public. The silence on race is hard and absolute but fogged by southern manners. The election seemed like it could become a venue for people to air their grievances, but who knew where that might lead?

Donato is a perfectionist, so he doesn’t entirely trust others’ views of his work. The media had latched on to his story for the least relevant reason: that he began to learn photography while in federal prison. He could already see that that sort of interest was limiting, not just to his career—once the novelty waned, they’d be off to something else—but to who he was as an artist and person. But the attention and praise were still new enough to him that he was grateful, disbelieving, and a little suspicious getting the assignment out of the blue. (He’d have no reason to know it, but it’s unusual for a lit journal like ours to commission photos in this way, and it’s the first issue since its founding in 1948 to use color on inside pages.) In any case, he wasn’t sure what to make of me and my admiration. After we got comfortable, he admitted that when I offered the commission he asked friends if they thought I might get him down here and kill him. There were a couple of times that intense week I thought about it, but the moments always passed.

When we got back to Lake Charles, I drove him around for an overview. He wasn’t impressed. Down by campus he said it all looked like New Jersey. He’d expected, I began to understand, some prototypical Southern town. He mentioned In the Heat of the Night. I got him something to eat and took him to his cheap motel, where he seemed discombobulated and couldn’t find his things. He pointed out that a low wall outside his window would allow thieves to break in and steal tens of thousands of dollars worth of gear. He asked again what the assignment was, exactly, and I showed him the locations list and said not to worry; we’d just go out the next day and see what we could get into. He didn’t seem convinced. I went home with a terrible ache in my shoulder and neck, right about where the aesthetic gland is located. He barely slept that night for noise and the fear of robbery.

When I picked him up early the next morning and moved him to a new motel, he admitted he was worried. He wasn’t seeing anything to shoot, and he found it bizarre there weren’t any people, which was a problem for someone who shoots faces. People were driving around, of course, locked up in their pickups and cars, and others were presumably inside their houses and businesses set back from the roads. But there was no human bustle or interaction as he was used to, and it was kind of creeping him out, he said, as if something bad had happened and we hadn’t heard about it yet.

Our first stop, after a quick dyspeptic breakfast, was North Lake Charles. It’s known as the black side of town, and there, thankfully, people were out walking and sitting on their porches and working on cars. The neighborhood broke the gloom, and I thought back to when the guy who hired me asked my early impressions of the town, and I’d answered that it seemed to me whites had all the power but the black community had the vital culture, and he said I’d got it right. Donato began to twist in his seat with excitement, looking at passing faces, signs, and buildings with compositional interest. We got out and talked to residents, went to churches, stores, a scrap yard, and were welcomed graciously by all.

Our first stop, after a quick dyspeptic breakfast, was North Lake Charles. It’s known as the black side of town, and there, thankfully, people were out walking and sitting on their porches and working on cars. The neighborhood broke the gloom, and I thought back to when the guy who hired me asked my early impressions of the town, and I’d answered that it seemed to me whites had all the power but the black community had the vital culture, and he said I’d got it right. Donato began to twist in his seat with excitement, looking at passing faces, signs, and buildings with compositional interest. We got out and talked to residents, went to churches, stores, a scrap yard, and were welcomed graciously by all.

Once Donato was charged, we worked continuously for four days, dawn until the light failed, moving around the city and beyond, rarely failing to find subjects. I served as driver, production assistant, fixer, and interviewer, and fell asleep in a chair at the end of each day, emotionally as much as physically exhausted. He may or may not be correct that he’s not suited by temperament or vision to journalistic coverage of an event, such as a Presidential election, but he was perfectly suited to capturing a humanistic view of all those we met that week: homeless, addicts, clergy, churchgoers, business owners, a tattoo artist, a housekeeper, voters and pollsters, drug dealers, fishermen, police, local vacationers on the Cajun Riviera—a cross-section of the human comedy of Lake Charles, Louisiana.

It wasn't just his eye, his energy, endurance, fearlessness, and sense of adventure. Subjects love him, I discovered. He never pushes; if someone says they don’t want to be photographed, he moves on. But they rarely say that, since he establishes instant trust and rapport. He touches their faces, manipulates bodies, bears witness to exactly who they are.

It wasn't just his eye, his energy, endurance, fearlessness, and sense of adventure. Subjects love him, I discovered. He never pushes; if someone says they don’t want to be photographed, he moves on. But they rarely say that, since he establishes instant trust and rapport. He touches their faces, manipulates bodies, bears witness to exactly who they are.

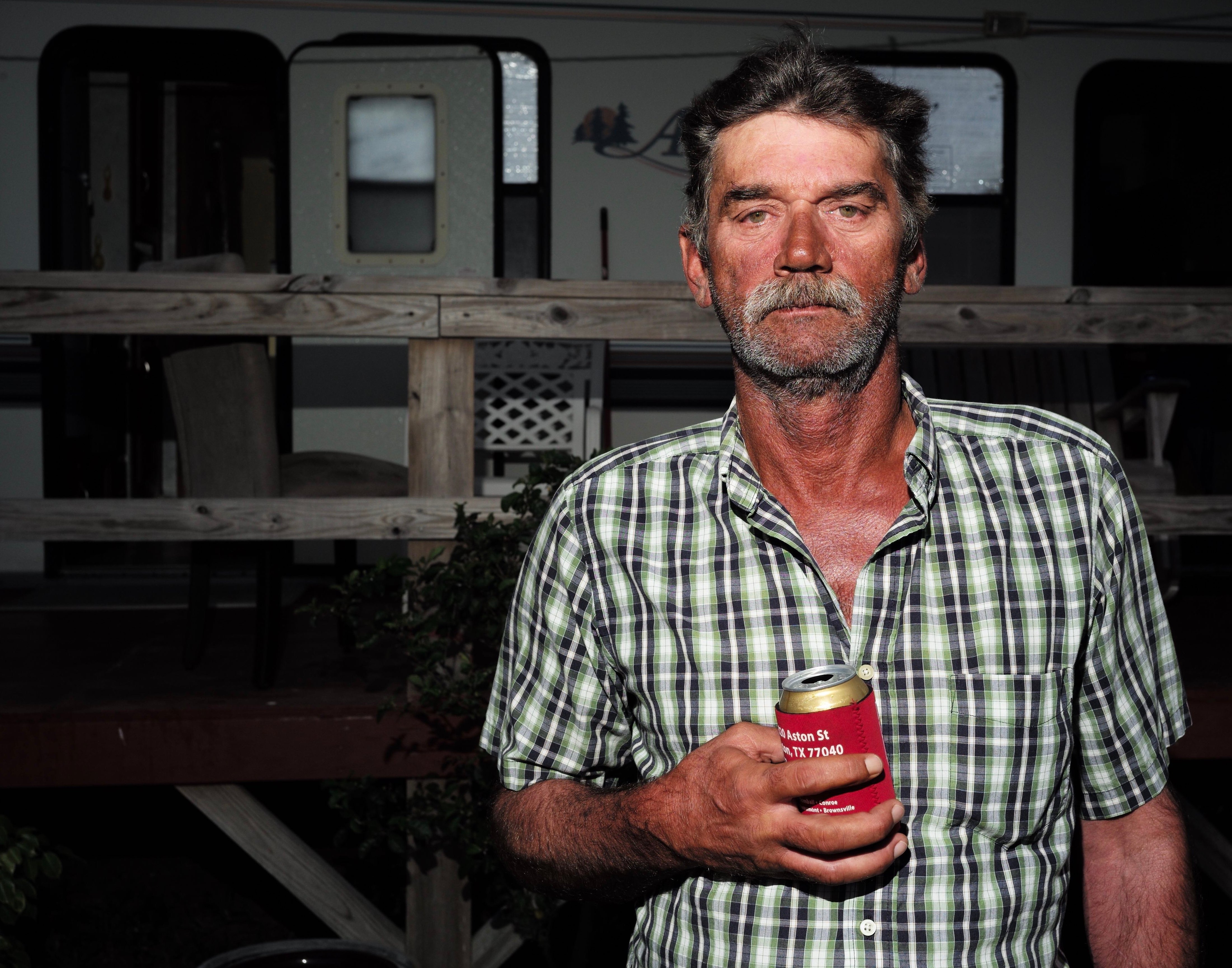

Will and LaDonna, for example, a couple we found together on the street, melted as soon as Donato rolled down the car window and yelled, “Hey, how you guys doin’?” LaDonna said she knew by looking at him that he had lived through some stuff. We got out, and they discussed the dangers of krokodil. Will offered the camera his ravaged teeth, which a Medicaid dentist had finished ruining before coverage ran out. LaDonna was anemic and cold in her hoodie. She gave us hugs and listed off “the five worst hoods in Lake Charles,” so we would be safe. “This place is heaven compared to others we’ve lived in,” she said.

Will and LaDonna, for example, a couple we found together on the street, melted as soon as Donato rolled down the car window and yelled, “Hey, how you guys doin’?” LaDonna said she knew by looking at him that he had lived through some stuff. We got out, and they discussed the dangers of krokodil. Will offered the camera his ravaged teeth, which a Medicaid dentist had finished ruining before coverage ran out. LaDonna was anemic and cold in her hoodie. She gave us hugs and listed off “the five worst hoods in Lake Charles,” so we would be safe. “This place is heaven compared to others we’ve lived in,” she said.

Marvin, having morning coffee at a little table behind his house, talked about his job as a longshoreman at the port, which is what Donato’s dad had done for a living in New York. Donato asked me to take a photo of them together.

Marvin, having morning coffee at a little table behind his house, talked about his job as a longshoreman at the port, which is what Donato’s dad had done for a living in New York. Donato asked me to take a photo of them together.

Mrs. Craven, a leader in the United Daughters of the Confederacy, invited Donato to stay with her family any time he returned to the area. She gave us jars of homemade jam and satsuma oranges from their tree, and her husband explained the meaning of their Confederate bearer bonds.

A little one was christened, family all around and Donato on the edges, as the choir rocked and a teenager beat a trap set in a plexiglass booth next to the pews.

A little one was christened, family all around and Donato on the edges, as the choir rocked and a teenager beat a trap set in a plexiglass booth next to the pews.

A young man named Keith, outside the Hardee’s after a casino nightshift, chatted as he posed, his pompadour shining in the morning sun. He got on his motorcycle and rode off to get some sleep, but two minutes later texted to say that Donato was a handsome man and should come by the casino that night.

The Lake Charles SWAT Team released their attack dog on Donato—twice—to everyone’s laughter and delight, most of all Donato’s.

Joe, who was living under a gazebo on the lakefront by the tiny yacht club, wanted Donato to know he isn’t homeless, that he’s on assignment himself for a project on being homeless, and the three-month job turned into six months, then a year, and now he can’t imagine going back to his life.

Joe, who was living under a gazebo on the lakefront by the tiny yacht club, wanted Donato to know he isn’t homeless, that he’s on assignment himself for a project on being homeless, and the three-month job turned into six months, then a year, and now he can’t imagine going back to his life.

Our cover subject served in Vietnam, worked the petro plants and port for decades, and is now retired. He was in his rocker on the porch of his trim little house, and he issued orders to his young son to trim the lawn while he sat with great dignity for Donato’s portraits. I leaned on a railing and asked questions until I noticed I was standing in a fire ant mound. The old man got a can of Raid and sprayed down my bare feet and legs then squirted the inside of my running shoes full. I retreated to the car to nurse my dozens of bites. He and Donato remained cheerful together through it all.

Our cover subject served in Vietnam, worked the petro plants and port for decades, and is now retired. He was in his rocker on the porch of his trim little house, and he issued orders to his young son to trim the lawn while he sat with great dignity for Donato’s portraits. I leaned on a railing and asked questions until I noticed I was standing in a fire ant mound. The old man got a can of Raid and sprayed down my bare feet and legs then squirted the inside of my running shoes full. I retreated to the car to nurse my dozens of bites. He and Donato remained cheerful together through it all.

Two days after the national election was announced I went to get Donato for the last time, to drive him back to Houston. Travelers from Alabama sat next to us in the motel’s crowded breakfast room and shook their heads at Fox News coverage of liberal protestors elsewhere in the nation. Donato commiserated and said flag burners should go straight to prison. Then he watched an interview with Chris Christie with amusement and said, “Dat clown will be the first guy to go down.” (Christie had “transformed himself into a sort of manservant...constantly with Trump at events” in the lead-up to the election and was head of Trump’s transition team for three days past the election, but did not take the cabinet posts offered.)

Two days after the national election was announced I went to get Donato for the last time, to drive him back to Houston. Travelers from Alabama sat next to us in the motel’s crowded breakfast room and shook their heads at Fox News coverage of liberal protestors elsewhere in the nation. Donato commiserated and said flag burners should go straight to prison. Then he watched an interview with Chris Christie with amusement and said, “Dat clown will be the first guy to go down.” (Christie had “transformed himself into a sort of manservant...constantly with Trump at events” in the lead-up to the election and was head of Trump’s transition team for three days past the election, but did not take the cabinet posts offered.)

In the end, public gestures of representative democracy were not the focus for our New York Yankee in King Cotton’s court. Nothing happened here, after all, before, during, or after the fraught election—neither protests nor gloating, let alone unrest. Social norms and the veneer of southern politesse had held. Still, his lens captured American truths, and I was sorry to see him go. It was chilly out, 68 degrees with a breeze off the Gulf, low scattered clouds, and the sun like a weak bulb as we started out in the new era.

In the end, public gestures of representative democracy were not the focus for our New York Yankee in King Cotton’s court. Nothing happened here, after all, before, during, or after the fraught election—neither protests nor gloating, let alone unrest. Social norms and the veneer of southern politesse had held. Still, his lens captured American truths, and I was sorry to see him go. It was chilly out, 68 degrees with a breeze off the Gulf, low scattered clouds, and the sun like a weak bulb as we started out in the new era.

All photos courtesy of Donato DiCamillo. This piece is adapted from my introduction to Donato’s photos in the McNeese Review, Volume 54, 2017.