You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

In October 2014 I discovered a Kickstarter campaign by Griffin Dunne—actor, director, and nephew of Joan Didion—whose goal was to finance “the first and only documentary being made about Joan Didion.” Dunne would be co-director. The working title was “We Tell Ourselves Stories In Order to Live,” a line from her White Album, which, stripped of context, sounds both hopeful and self-justifying.

Dunne’s co-director was a longtime editor for director Michael Apted; producers included a Didion niece and a Ric Burns collaborator; and the campaign worked with “a creative services agency that gets projects financed through crowdfunding with a 100% success rate.”

“When you donate, you are proving that there is a huge, hungry audience for a documentary about Joan,” they said. Proving? I wondered who’d turned them down for funding and why.

I also wondered why they needed crowd-sourced money. When Griffin Dunne got married for the third time, in 2009, to designer Anna Bingemann, “They were joined by [Nicole Kidman, Keith Urban, and] Naomi Watts and Liev Schreiber, who took their sons Alexander and Samuel. Keeping them company were Hugh Jackman and Deborra-Lee Furness, Uma Thurman, Sacha Baron Cohen and Isla Fisher, Mark Ruffalo and Suze DeMarchi. The ceremony and party took place in Dunne's sprawling gardens. Bingemann, whose family is part of the Perth Sterlings retailing dynasty, wore a cream ‘bohemian’ gown from the French fashion house Lanvin.”

Dunne and company asked the crowd for $80,000. They got $221,085 from 3,564 individuals—plus fifty bucks from me—and entities such as vogue.com. Then they made a deal for the film to become a Netflix Original with worldwide distribution.

Kickstarter campaigns usually offer incentives for donations. The trick is to make rewards seem worthwhile without eating into the funding. At the $50 level I was to receive several things, including “ACCESS...you will get updates regarding the film: all of the behind the scenes anecdotes, images, and clips. Welcome to the team.” There was also “an oral history of Joan's life and work”; a PDF of Saturday Evening Post columns written by Didion and her husband, John Gregory Dunne (“one of the best[?] literary couples of our times”); “a [PDF of a] handwritten list of Joan's 12 most important books to read before you die.... Try to read one every month for the year”; and a PDF of “her recipe book [that] represents a lifetime of entertaining...all perfectly preserved in her handwriting.” There would be a free digital download of the film when it was finished.

There was a whiff of the amateur, even the unseemly, about the campaign. Some of that could have been a result of various levels of campaign organizing and copywriting that confuse issues of family, access, and wording, such as “the best literary couples,” which is not something anyone in the literary world would ever say. Organizers said if you wanted to reach Didion, you could write a two-page letter on what she meant to you, and her family would read it to her; this cost $350. But, “No gift is too small,” they wrote. Updates on the film got spotty and never gave much ACCESS, then radio silence set in. I don’t recall getting the oral history; the book list is only surprising in how unsurprising it is (lots of James, Farewell to Arms, Notes of a Native Son, Executioner’s Song, etc.). The recipe book is abridged and cribs from House & Garden, Good Housekeeping, All-Clad, and Williams-Sonoma.

But these were only gimcracks; the film was the thing. What I really wanted, as a nearly lifelong Didion fan, was the documentary that should already exist—something insightful and artistic in its own right, a Beatles Anthology in comprehensiveness, a Last Waltz of her in archival action, a Swimming to Cambodia regarding her process and reflections on the art.

“Incredibly, this story has never been told,” the campaign pitch said. “Now that we have the access, we must tell it. This is our chance to be Joan's witness.” (Now we have access? Did Didion resist her family making the film? What changed her mind? Or was that the sentiment of some lower-level producer? And wasn’t Joan Joan’s witness?) “While her writing is fierce and exposed, Joan herself is an incredibly [my emphases] private person. We have the privilege to know Joan as a subject and also as a member of our family.”

Those two “incredibly”s cancel each other, of course. Didion’s sense of privacy at least partly explains the lack of a previous film or more books about her. Tracy Daugherty, with whom I worked as editor on a different book, was not granted access to Didion or many in her circle when he wrote his recent biography. Of course, by cooperating with an outsider, any subject might end up a collaborator in her own unflattering portrait. But there are hazards too in keeping it in the family, including a documentary that’s merely respectful or affectionate. If Didion actually wanted a legacy film, couldn’t her connections and cooperation have gotten anyone in the world for the project?

Three years passed, and I started reading about the finished film in the press, then saw it was a festival contender. On August 25 of this year I got an email that apologized for the “long silence” and said the film was nearly ready. At the end of October an email announced the Netflix deal; unfortunately Netflix wouldn’t permit the digital download, but there was a code for a free month of Netflix; be sure to watch before your month runs out. It was ridiculous to feel a twinge of irritation, like some stockholder with a .02 share, but hadn’t Griffin Dunne said, “And by supporting this campaign, you are actually making this film with us”? I didn’t even get to see the coffee carried, and I would gladly have done it myself, if Dunne had let me erect my pup tent in his sprawling gardens.

***

I’ve watched the documentary three times. To start with, I’m not sure how many of the campaign’s stated goals were met:

I’ve watched the documentary three times. To start with, I’m not sure how many of the campaign’s stated goals were met:

“We Tell Ourselves Stories In Order to Live traces the arc of Joan’s life through her own writings, and in her own voice. Our film will tell Joan’s story through passages she has chosen (and will read aloud) from her work, as her friends, family, colleagues and critics share their accounts of her remarkable life and writing. Patti Smith, Vanessa Redgrave, Allison Janney, Graydon Carter, Robert Silvers, and Bret Easton Ellis are just a few of the people we’ll interview.

“We want to honor Joan's language, to visualize the stories she tells, to put her words to picture. Joan’s obsessive memory, and her sharp and unsettling observations, will be brought to life, using music and images–rare and atmospheric film and stills that encapsulate her words. We will also be using rare archival from Joan’s personal life and family history.”

Not all the interviews were done, apparently, or made the cut. (The film is an hour and 38 minutes long and includes other interviews, such as Hilton Als and Calvin Trillin, who are terrific and moving.) Historical context is never provided as well as Didion herself does it. There’s little critical-intellectual engagement. And this business of putting “words to picture” often feels disconnected or weak—many times, eg, we have no idea if we’re looking at stock photos/footage or her own archives. It’s a minor film on someone who has been a major figure in my reading, thinking life.

The “family” approach does, however, accomplish one thing it apparently set out to do: create a sense of intimacy. The film feels personal. In one scene Griffin sits with Joan on her sofa and recalls being a child at a pool party that she and her husband attended. “Here’s, like, my five-year old memory of meeting you,” Griffin, a 62-year old man, says shyly as they page through a photo album together. He recalls how one of his balls had fallen out of his fancy swimsuit, and the men in the family, even his own mother, roasted him for it. “I was scarlet. I was so embarrassed,” he says. “And you were the only one that didn’t laugh. You just kept right on going, with a totally straight face. I always loved you for that.” Joan squirms with silent laughter punctuated with squeaks of delight. There’s the feeling it’s a family classic, which calls into question how much of Dunne’s telling is performance.

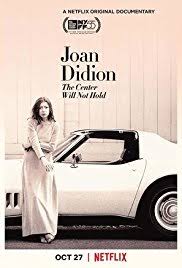

The film also bears down on the premature losses of Didion’s husband and daughter, written about in two of her most recent books, Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights. Why that focus, in a whole-life honoring? Was it because it’s the portion of Didion’s life that Dunne has shared most directly? Or did Didion herself push in that direction? In any case, her longing, grief, and isolation are so present, overriding so much else that might be portrayed, that even the title of the documentary had to change, to Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold. This shift in focus is the larger accomplishment of the film, but I’m not sure the makers intended it.

Here’s the full quote from Didion’s The White Album that contains the film’s original working title:

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live. We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the ‘ideas’ with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.”

That is rather more clear-eyed than the sentiment of the first sentence by itself, and it’s what many of us have valued in Didion’s work. When this negative idea about telling stories is combined with the Yeats poem that serves as epigraph to Slouching Towards Bethlehem—“Things fall apart; the center cannot hold; Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world...The ceremony of innocence is drowned”—we can grasp Didion’s lifelong view of life’s “atomization,” of entropy, of defeat as a normal, even banal, consequence of being alive. The tragedy—not the perfect word—portrayed in the documentary is that this lion of our literature, who achieved fame, fortune, and canonical acceptance, and whose work will endure, suffered unexpected, intolerable losses late in life that seem to illustrate the working thesis she’s had at least since her 20s.

Didion is elderly now—just turned 83—in psychic pain, and frail. (She complains that people comment on her weight and insists she’s weighed the same since her twenties, but the film reveals she was down to 75 pounds at one point.) Her long-diagnosed MS perhaps makes her arms move on their own, and she often struggles to speak. What revelation is at hand for us if even Joan Didion can lose her eloquence? We wish our icons to stay holy, untainted by the profane, immortal.

Long scenes in the film of Didion doing little more than making watercress and cucumber sandwiches and cutting off their crusts are heartbreaking in their way. They show very clearly, as she performs this domestic ritual of decades, now alone, how the center cannot hold. I wept at Didion’s Blue Nights without loving it, but to actually hear her say aloud, “One of the things that worries us about dying is we're afraid always we're leaving people behind and they won't be able to take care of themselves. We have to take care of them. But in fact...you see, I'm not leaving anyone behind,” in a quavering voice.... This view of loneliness is so personal it feels like a violation. The filmmakers said they would bear witness. What did they have in mind?

Yet this is what Didion wanted all her life, right? The clear-eyed view? “I've always had this sense that the unexamined fact is like a rattlesnake. It's going to come after you. And you can keep it at bay by always keeping it in your eye line,” she told the Guardian in 2011. When familial disaster revealed the truth that she had not been seeing clearly, she wrote about that too, and, again, we loved her for it.

But we have our own idee fixe in this, which is about the redemptive power of art, the struggles of form and process as salvation. Surely by writing those books, Didion made some degree of peace with her loss and connected with readers in a community of grief and the celebration of life. The documentary seems to show otherwise. Perhaps this was her last gift to us, since she’s said she may not write more books: What if to understand is to be crushed for the vanity of trying to understand? Only our need for narrative, for happy endings, for justice and redemption, delude us otherwise.

“I used to say I was a writer, but it’s less up front now. Maybe because it didn’t help me,” she said, after Blue Nights. I’ve always thought Joan Didion helped me, and that recapturing reality should be a goal—more than ever in our current era. It’s the honor we pay life by not dismissing it with delusions, fantasies, and desires.

We can’t know the whole book of the world, but it’s not that there are no answers in fragments. How else to start? I carry around Didion’s most recent book, South and West, where I live in the South, as if it were a collection of ancient poetry fragments. The book comprises hard observations on race, culture, and personality, extracted from her notebooks written on a month-long visit to the deep South in 1970. Nathaniel Rich, in the foreword, calls it, despite its unfinished nature, “the most revealing of Didion’s books.” “Readers today will recognize, with some dismay and even horror, how much is familiar [in Trump’s America] in these long-lost American portraits. Didion saw her era more clearly than anyone else, which is another way of saying that she was able to see the future.”

Didion’s pages have shown us, among other things, how to have the courage to face our past, present, and future, and not have them warp or silence us. To see in fragments and impressions, lacking a coherent narrative. The documentary provides one more view. At the end of it we watch her move unsteadily down a hallway lined with family photos, toward a large mirror, and turn the corner, leaving us behind. In the end we get what’s coming to us, every penny.