You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

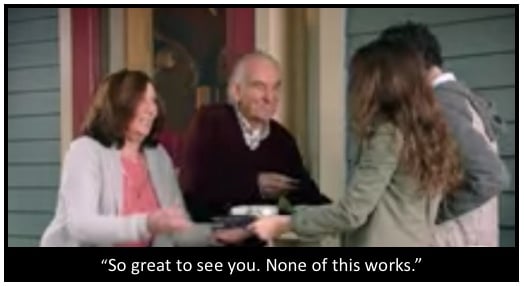

Credit a 2016 Ally Bank commercial with one of the more effective efforts to explain the tech experience and frustrations of many (often older, non-techie) individuals. As their two grandchildren excitedly rush up the front steps, the grandparents greet the them, arms extended, with laptop computers and cell phones: “Great to see you. None of this works.”

Why cite the Ally Bank commercial? Because Mark Lieberman’s Inside Digital Learning article this week on why many college and university presidents may feel insecure about digital learning reminded me of many conversations over the years with presidents and provosts whose reference point for “going digital” was often their children’s and grandchildren’s experience and expertise with IT. As campus leaders, these men and women were clearly proud of the work of their faculty and could readily cite the important research of their most prominent professors or some of the instructional innovations underway at their institutions. But it was sharing of a story about a child or grandchild that really highlighted the chasm between their own digital experience and expertise and that of their family members – and by extension, the digital chasm between themselves and many of their faculty and students.

Somewhat surprisingly, the experience of some corporate executives suggests a strategy for presidents, provosts, and other senior campus officials who would like to enhance their tech skills and better understand the digital pedagogies and learning experiences of their students. Two stories, from the executive offices of tech titans IBM and Microsoft during the early 1990s, may be useful for many campus leaders in 2018.

Let’s begin with Microsoft, which paid little relatively attention to the emerging Internet in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Microsoft’s (then) young co-founder and CEO, Bill Gates (b. 1955), focused his company on expanding (and protecting and defending) the firm’s hold on the profitable operating systems (DOS and Windows) and application franchises (Word, Excel, PowerPoint, etc.) that had become almost ubiquitous on personal computers across the globe. Gates and his colleagues were aggressive if at times myopic competitors, determined to address the expanding needs of consumers and corporate clients while attempting to contain firms such as Apple, Ashton-Tate, Borland, Lotus, and Word Perfect, among others, which they saw as threats to Microsoft’s profitable hegemony in operating systems and software applications.. (Note that only Apple survives today as a recognizable brand.)

What led Bill Gates and others in Microsoft’s leadership team to look beyond their screens to the larger, connected world of the Internet? It was the steady stream of Microsoft’s new hires from American colleges and universities who experienced the early Internet as undergraduates. The newly hired students sounded the alert that something really big and important was happening on college campuses.

It was the recent college graduates at Microsoft, often a dozen years younger than their leaders and supervisors, who ultimately led Gates and his executive team to acknowledge that attention must be paid to the emerging Internet. And in a pivotal May 1995 internal memo, titled The Internet Tidal Wave, Gates proclaimed that because “the improvement in computer power will be outpace[d] by exponential improvements in computer networks . . . . I now assign the Internet the highest level of importance” to the future of Microsoft.

As Microsoft was advancing during the economic downturn of the early 1990s, computer giant IBM was in significant decline. From 1990-1992, IBM’s US workforce declined 23 percent. In 1993, the company cut an additional 25,000 jobs world-wide and also reduced R&D expenditures by $1 billion (15 percent).

The individual selected to lead IBM out of its downward spiral was Lou Gerstner (b. 1944, a decade ahead of Bill Gates), who previously served as chairman of RJR Nabisco, and before that, as a senior executive at American Express. There was nothing in Gerstner’s background to suggest he was the ideal candidate to lead one of the world’s most prominent tech companies. Moreover, Gerstner was the first outsider selected to lead IBM; previous CEOs had all risen through the ranks. (Sending a small shock to IBM lifers who lived with a corporate dress code that dictated white shirts, Gerstner notoriously wore a blue shirt on an early visit to IBM’s corporate campus in Armonk, NY.)

Yet Gerstner, who served as CEO from 1993 through 2002 and has been credited with reviving IBM, obviously had other qualities which lead to his appointment as president and CEO. To school himself on IBM’s technology, Gerstner retained a group of young tech tutors.

Gates and Gerstner are not alone among CEOs, in tech firms and elsewhere, who have retained younger tech personnel to serve as their tutors. By doing so they acknowledged the distance between themselves, the products and services provided by their firms, and the experience, expertise, and expectations of clients and employees.

The CEO’s tech tutor is not on hand to do weekly “show and tell / let me show you something interesting” sessions. Rather their role is to school the boss on a world beyond the C-suite that they may not know, but really need to understand to be effective leaders.

For presidents and provosts/CAOS on edge about IT and digital learning, “tech tutors” – either students or younger faculty, perhaps based in the same major or field as the tutee – provide a simple and effective strategy to assist and inform senior campus officials who truly want to enhance their understanding of the rapidly evolving world of digital pedagogy.

Follow me on Twitter: @digitaltweed

ALSO OF POTENTIAL INTEREST: TO A DEGREE, the postsecondary success podcast of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.