You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Faculty members at all levels engage in mentoring and advising. Yet the midcareer years can feel like something of an onslaught as professional and departmental demands increase considerably, while faculty are still working on developing their own careers. Junior faculty members are often protected from mentoring responsibilities, but many midcareer faculty face high expectations to provide mentoring to not only students but also their colleagues.

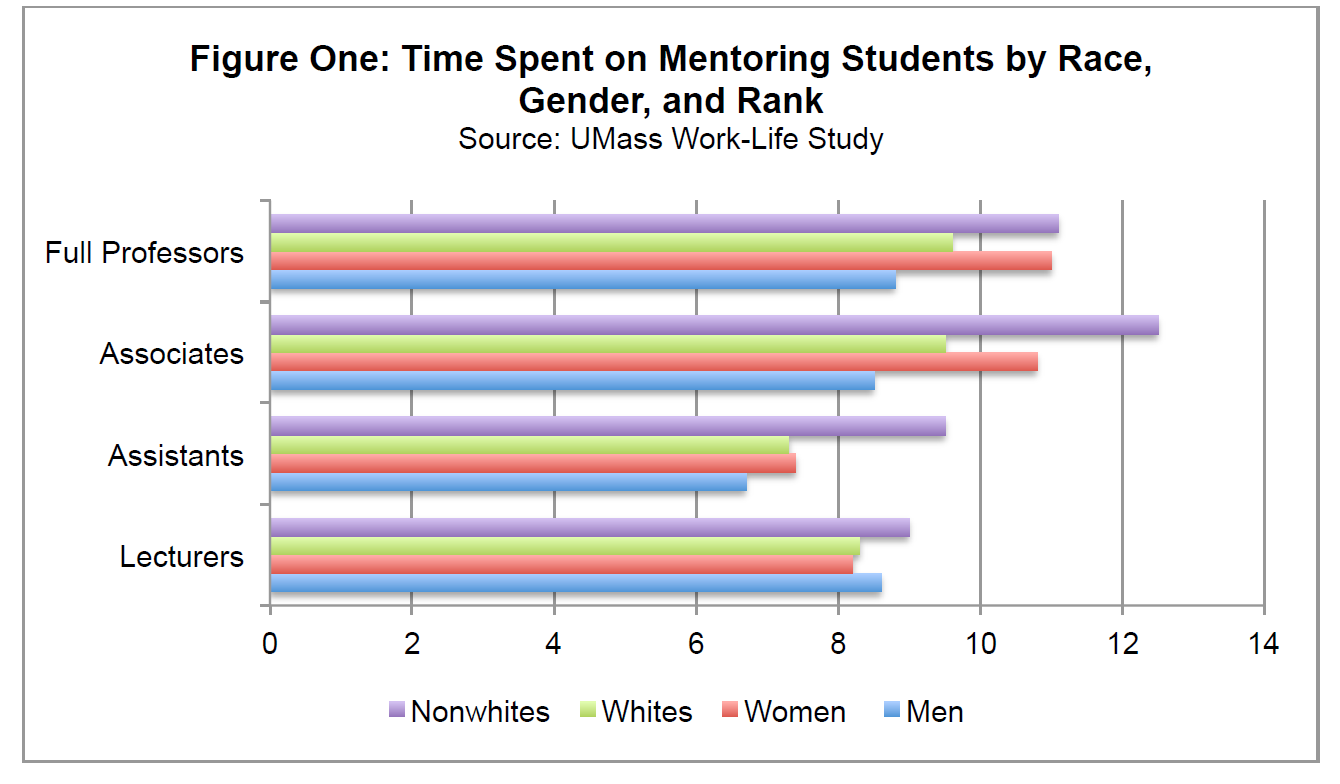

In research at our institution, we asked faculty members how much time they spent mentoring and advising students. We found that, on average, associate professors spend about 10 hours a week, while assistant professors spend seven hours. The additional three hours per week adds greatly to the workload of new associate professors. And since most associate professors also engage in peer mentoring of colleagues, those numbers in fact underestimate the impact of mentoring on midcareer faculty members’ workloads.

The chart above shows that faculty members at our institution spend more time mentoring and advising students as they move up in rank -- although lecturers tend to spend more time on advising students than tenure-track assistant professors (except for nonwhite faculty members). That is one of the many challenges that the adjunctification of the faculty has created, whereby non-tenure-line faculty, who are actually most vulnerable, carry out key elements of faculty work. On our campus, for example, many lecturers are providing needed advising to undergraduates.

Women spend more time on advising than men at every rank, except among lecturers. That may reflect gendered expectations from students for women and colleagues to provide mentoring and support those around them. Faculty members of color have the highest rates of advising at all ranks, which may reflect pressures to provide mentoring and support to students of color. Workload around mentoring and advising is high for women, and particularly high for faculty of color. All of this indicates inequities.

Mentoring requires an investment of time, which most faculty members feel is in short supply. Indeed, when we asked faculty members about the challenges they faced, all of them noted that time was their key challenge. In addition, funding agencies, like the National Science Foundation, increasingly ask researchers to communicate their mentoring approach, identifying strategies they will use to help students learn research skills. Developing effective mentoring structures helps faculty members meet these requirements. At the same time, most faculty members have not been trained to mentor.

Given that demands for mentoring appear to expand in midcareer, what strategies might help faculty members provide quality advising and mentoring while setting limits? We suggest that institutions and faculty members consider the following:

Providing recognition. Colleges and universities ask faculty members to do more and more with less and less. Given the pressure to produce scholarly work, achieve high teaching evaluations and engage in academic leadership and service, mentoring may take a backseat in many faculty members’ schedules. Publicly recognizing the important place of mentoring and advising is a crucial step an institution can take to help place a priority on those activities.

Some institutions and departments give faculty members credit for mentoring, for example, by reducing the course load for active mentors. For example, if the average teaching load is 2/3, faculty members who are advising more than the average number of students might be eligible for a 2/2 teaching load. Another approach might be to provide a teaching or service reduction for each Ph.D. student who graduates.

Documenting mentoring and weighing it in personnel and merit recommendations is another approach. Some institutions document formal mentoring that faculty members provide students through honors theses or master’s or dissertation committees. Many do not fully credit the time faculty members spend advising undergraduate students, sponsoring student organizations, writing letters of recommendation or informally mentoring students or colleagues. Formally recognizing the value of this invisible work draws attention to the myriad ways that faculty members work to support those around them. Creating mentoring awards is another way of highlighting the importance of mentoring to the institution.

Such strategies suggest that institutions can play a key role in helping faculty members juggle competing demands and value mentoring. They can also help address the imbalances in mentoring by race and gender that our research has identified.

Reserving mentoring time. If mentoring is an expected part of a faculty member’s workload, one way to push back against other demands is by setting time aside for advising work. That can be crucial, since student progress often relies on advising and timely feedback from faculty members.

Setting regular mentoring hours is one way of ensuring that meetings with students do not bleed into every other hour of the day. Some faculty members use scheduling software that allows students to sign up for advising slots. This allows faculty members to limit their meeting times, know who plans to meet with them and avoid having a long line of students sitting on the floor outside of their office. Similarly, some faculty members also schedule time in their weekly schedule for providing feedback to mentees. Peer mentors can also actively reserve mentoring time, for example, meeting with colleagues for support one day a month or scheduling peer-mentoring groups at particular times.

Many people wish for mentors that are responsive. As one student noted, “They don’t need to respond to emails immediately, but within a couple of days would be great.” Yet being responsive does not necessarily mean providing feedback immediately as much as responding to students who send work and letting them know when to expect feedback. Developing a rhythm, so that those seeking comments send work far enough in advance of meetings to allow time to review it, can help stimulate “a productive discussion about the work,” in the words of one student. Mentees can help participate in this process by negotiating a reasonable date for feedback or by scheduling an appointment to discuss the work.

Practicing clear communication. The faculty members we spoke with also identified effective ways to communicate with mentees, such as asking them to write weekly or biweekly emails or keep an online log that that mentors can review before meeting with them. Practicing effective communication strategies may be particularly important when geographic distances make meeting in person difficult. For example, graduate students in the field may write private blogs that allow mentors to provide feedback on their research strategies or the challenges they are facing.

Faculty members also recommend that undergraduate or graduate students write up a summary of meetings, which helps ensure that both sides have the same understanding about the conversation. One faculty member noted, “One of the best things I've learned to do is to have students write up a brief paragraph after our meetings, restating what we talked about and what we agree will be the next steps for the student. This provides us with a kind of social contract, allowing me to clear up any miscommunication, establishing goals, keeping us in regular contact, etc. … I encourage students to brood over the conversations for a few days before writing to me. I've found it to be quite effective.”

Mentors can communicate not only about research progress but also about career developments, such as “opportunities like conference attendance and presentations, funding/grants/awards, workshops/seminars, and employment.” Forwarding announcements of this sort is not necessarily time-consuming and helps maintain a sense of connection and recognize the mentee’s professional goals. Such efforts can also provide essential support to students and junior colleagues, who may feel uncertain about which opportunities to pursue.

Engaging in group mentoring. Faculty members also suggested group-mentoring strategies, where students meet jointly with a faculty member to discuss their research. That enables faculty members to work consistently with mentees while limiting the number of individual meetings required. This approach may occur fairly naturally with scientists who train students in lab and can be used in other disciplines, even when students are pursuing different types of research.

One of the greatest successes of this strategy is that it helps students learn from peers and develop peer-mentoring networks outside of interactions with faculty members. It can work through peer-advising models, helping undergraduate students identify courses or internship opportunities, as well as for graduate students, who can support one another around research, teaching and professional development. As one student noted, “I have found some of the most helpful mentoring from other graduate students who have more experience with something (like publishing).” This can be helpful in both directions, as giving feedback to others can help catalyze realizations about your own work.

Group mentoring can also be very effective in peer mentoring models, where colleagues meet to discuss one another’s work or simply have conversations and seek advice about professional decisions. For example, biweekly brown-bag lunches aimed at providing feedback to colleagues’ work can also be a form of mentoring.

Sharing effective mentoring practices. Mentoring is not often taught; faculty members usually learn how to mentor based on how they were mentored. Yet most of the faculty with whom we spoke suggested that they learned what not to do as much as what to do from their mentors. One noted, “To be glib: I just think about what my mentor would do, then I do the opposite.” As Sonja K. Foss and William Waters argue, many faculty members want their mentees to succeed, but “simply don’t know what to do to be good advisers.”

This suggests that faculty members need opportunities to talk with colleagues and students about how to mentor effectively and to identify strategies for mentoring. There are many excellent resources to consult, including materials from the University of Wisconsin and University of Michigan, and mutual mentoring materials from the University of Massachusetts. At the same time, peer support or mutual mentoring helps address the conundrum many associate professors face. These faculty members often note that, once they are tenured, they no longer receive mentoring -- just as they are being asked to provide more and more mentoring to junior colleagues and students. Yet given that academic careers consistently ask faculty members to take on new challenges, mutual mentoring models can help faculty members feel supported as they move forward in their careers.

While midcareer faculty members often are sandwiched -- facing very high expectations for mentoring with limited time for their own career advancement -- these strategies can help them address the challenges. Faculty members may practice specific strategies around reserving time, communicating with mentees and grouping students that may alleviate some of these pressures. Institutions can also work to provide more support for mentoring through peer mentoring networks that help identify challenges and successful strategies for resolving them. Yet, our most important point is that if institutions see mentoring as part of the faculty workload, they need to recognize this work and provide space for it.