You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

One of the central problems many midcareer faculty members face is how to preserve their time for research while contending with new demands on their time. As we have earlier described, reaching midcareer can be a surprising letdown. Rather than celebrating the success, many faculty members find themselves drowning in a sea of new responsibilities.

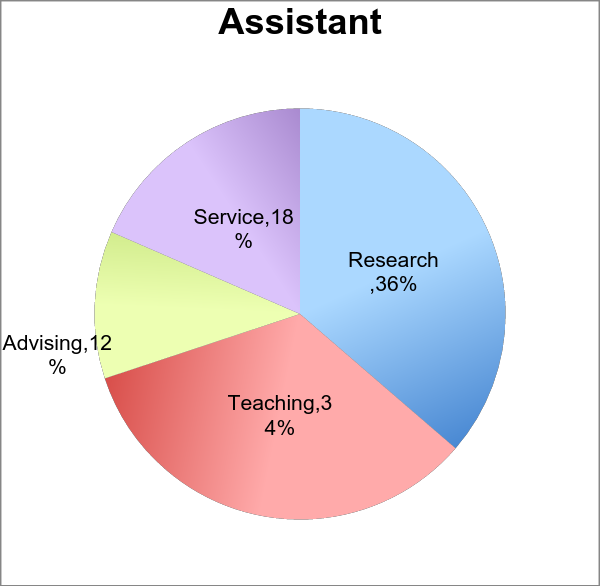

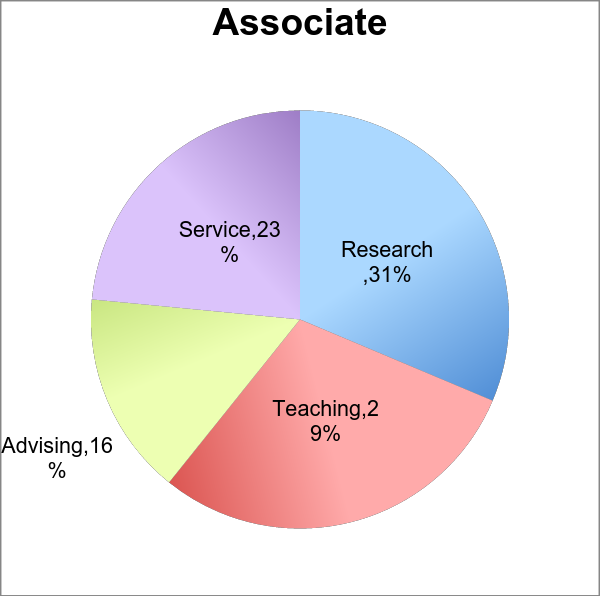

Survey research on faculty members at our institution shows that earning tenure does not dramatically reduce work hours but does change how much time they spend on research. While associate professors spend less time on their teaching, perhaps becoming more efficient with experience, they also spend less time on their research and more time on advising and service.

Figure 1: Average Reported Distribution of Type of Work Hours per Week, Assistant and Associate Professors at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst

Being strategic about how you divide your time across research, teaching, service and mentoring can help you feel more in control. One common recommendation is for faculty members to block off research time each week, not allowing other forms of work to intrude. Yet that is much easier said than done.

We talked to a number of faculty members at American colleges and universities on the phone, in person and via email and social media to understand their experiences with “protecting research time.” Many discussed how stressful and challenging it is to protect research time. They also shared strategies that they have used effectively to do so.

Challenges

One faculty member noted: “I've only spent about six hours on research this semester. Not per week. Total. … One of the big obstacles to getting work done is that the administrators in my college seem to believe that we're only ‘working’ when we are either with students or responding to various directives and information requests from on high.”

Another faculty member said, “It is difficult to prioritize your own need over others’.” That is a common sentiment, and one that we believe faculty must reconceptualize. Research is not me time -- it is a basic work expectation of faculty members, particularly those at research institutions, and also a benefit to the common good.

Yet deadlines related to teaching, advising and committee meetings are externally imposed, while most research deadlines are internally imposed. Thus, research gets pushed farther and farther back in the queue. One faculty member aptly summarized the situation, commenting that “urgent time-sensitive deadlines (typically totally unrelated to my research) often trump my research time that is not tied to a hard deadline.”

Service demands are particularly stressful, especially when senior administrators impose them. One faculty member argued that the university expects tenured faculty to “overextend [through taking on service]; there is no discourse about protecting the research time of an associate.” Another faculty member noted: “It’s not like we are bad at time management. It’s a choice -- take on more service or piss somebody off.”

Service demands may also lead to particular challenges for faculty of color, as we have previously argued. One faculty member described two semesters when she got very little research done. In hindsight, she realized that each semester included faculty searches that led to contentious discussions around race. She described the experience: “That work left me totally fatigued, and it was at times emotionally very challenging, which wasn't very conducive to … writing. I do think it was worth it. Deeply entrenched racialized ideas about whose scholarship and intellect count do need concerted efforts to transform. But it was tremendous amount of work that disproportionately fell on faculty of color.”

Although service may be the predominant research-disrupting force, teaching and advising responsibilities also push out research time. One faculty member observed: “Something else that probably cuts into my research time is my unproductive habit of actually preparing for my classes and giving students feedback on their work. It's totally self-harming behavior, because then you just end up with more students who expect you to teach well.” As in service work, doing a good job often leads to more work -- which can impede research time.

Strategies

Faculty members suggested to us a number of clear strategies that they use to great success. Key among them is developing a daily writing habit. One person told us: “I write first thing in the morning for about one to three hours after I wake up. This is my peak thinking and writing time. I try to do that at least four to five days a week.” Daily writing is effective because it keeps you habituated and eliminates time lost in regrouping and remembering where you were. As one busy but productive chair noted, “I get an hour of writing in a day if I'm lucky, and reserving entire days or half days for research are a thing of the past!”

That approach contrasts with “binge writing”-- writing over long periods for a few days. Yet some faculty members still find that binge writing can work for them. One commented: “They tell you not to -- but I do embrace the binge. Sometimes I get lunch and a giant brownie and a latte; I have written an entire draft of a manuscript on a brownie.”

Faculty members also described several key strategic approaches to protecting research time. We characterize these approaches into four types: escape, efficiency, visibility and accountability.

Escape. Many faculty members said they avoided their office or worked from home, which can help create clear boundaries between research time and other kinds of work (yet also blur boundaries between work and home). Others described escaping through structured writing retreats in fall, spring and summer. Retreats might take place over weekends, but scheduling retreats over regular workdays also works well. As one faculty member said: “Work can be so all consuming, and many people take research time out of their family. But the better strategy is to take it away from work.”

Another faculty member said she creates boundaries from service work during the summer, when she is not paid. She noted: “I use summer for serious research. I’ve gotten good at blocking off summer month[s] …. Last summer I wrote three book chapters for other people’s books and two chapters of my own book.” But, she laments, “then momentum is lost during the academic year.”

Yet another escape is by saying no when you can. One faculty member told us: “It’s important to be strategic in what to say no to. If the service won’t make a difference with regard to what the personnel committee can say about me in my promotion letter, I tend to say no.” Another faculty member said that her promotion pay raise would be $15,000. She argued: “Think of it as a $15,000 check you are writing someone else when you don’t make progress …. You don’t want to be bitter five years in.”

Efficiency. One faculty member described her reliance on an online writing group paired with a task management tool reminding her of tasks, including writing and posting to her online writing group. As a result, she said, “Dozens of times at 9 p.m., I’ve gone to write for half an hour.”

Another approach to efficiency is to outsource. A faculty member commented: “The one thing that does make a difference is having a research assistant. The two times in my life I've had one, even for just five to 10 hours a week for a few months, my productivity soars.” Another faculty member agreed, noting that even in the absence of formal funds, she will “pay graduate students out of pocket for work that is important to moving my work forward but would take precious time away from my writing -- like formatting bibliographies, double-checking manuscript formatting, literature searches, etc.”

One person with whom we spoke pointed out: “Before I had children, I procrastinated -- cleaning the house, cleaning my desk, before I could write a word. Now, I take any moment I can to write.” Another noted, “I’ve learned to work really, really fast, compress things. There’s not a moment that is not occupied, working very efficiently and multitasking.”

Yet she also identified drawbacks: “There is a pressure for everything to be efficient. It doesn’t feel creative, it feels assembly line.” As Madeline Elfenbein, a doctoral student at the University of Chicago, has observed, efficiency may mean working “mindlessly” -- which can lead to depression and, over the long term, lower productivity.

Another faculty member described to us the importance of maintaining reasonable work hours and enjoying life, commenting that “you could say those are impediments to research time, but they also make it possible for me to achieve what I do achieve, so they're enablers, too.” Faculty members also observed that exercise may be cut during busy times but may actually help boost creativity. That all suggests that efficiency cannot be the only goal.

Visibility. Another approach to protecting research time is to make visible or public your commitments. One faculty member argued: “I had to figure out what it takes to get them to leave me alone …. Editing a journal, which is more public, allows me to justify that I can’t do X.” Another noted that “the trouble of protecting time is often about not being clear with everyone about the expectations for your time from your department, college and national service …. You need to show all that is on your plate.”

Visibility can be used as a daily strategy, as well. One faculty member described using a kitchen timer to ensure that she gets at least six 10-minute writing blocks a day, a method that has become indispensable since she became a parent. The kitchen timer has the added bonus of making research time visible, as she noted: “I share this strategy with my colleagues and students for how to maintain writing productivity. An unanticipated benefit of this is that now all my students and colleagues know that when they see my timer going, I'm in the middle of a writing block and they offer to come back later.”

One faculty member commented: “The campuses that I have worked on typically do not gain momentum until 10 a.m. I write from 8 a.m. to 10 a.m. or 7 a.m. to 9 a.m. from Monday to Friday and schedule meetings and advising after 10.” By making visible that she normally cannot meet until 10 a.m., she has protected at least some research time. Other faculty members also discussed putting research time into their calendars and trying to keep meetings from intruding on that time. Yet one faculty member argued that sustained blocking off of time leads to other challenges. “In my experience,” she said, “the least obnoxious person in any group ends up caving in when you've got one person who protects mornings, one who leaves at 2 p.m. and one who commutes from far away and is only here two days per week. ”

Accountability. The final method for protecting research time is to create accountability mechanisms so that research-related tasks become as pressing as those related to service and teaching. That could include setting deadlines that you share with a writing group, which has consistently been associated with greater productivity. As University of Massachusetts doctoral student Travis Grandy has argued, establishing clear goals and communicating timelines to your peers can make a difference.

Faculty members also described incorporating grant submission deadlines and conference presentation deadlines into their calendars -- and using them as opportunities to turn internally imposed deadlines into externally imposed ones. One faculty member said, “I've noticed that when I have hard deadlines (grant deadlines), I always meet them without problem.” Conference presentation deadlines, particularly those that require full drafts of papers, can also help faculty members focus on research and get drafts completed in a timely way.

Another approach to “externalizing” deadlines was to collaborate on scholarship with other people and set group deadlines for completing work. Meeting deadlines for the group can help faculty members stay accountable for their research time. Some faculty members discussed collaboration as an approach that made spending time on research feel less self-indulgent. Faculty members who collaborate also recommended dedicated weekly research team meetings to keep the collaboration on track.

Over all, our discussions with faculty members suggest that protecting research time is not impossible, but it is challenging. While faculty members appear to embrace a variety of approaches for dealing with the issue, most described using more than one strategy -- there is no magic pill. But, as one concluded: “People who achieve do so not because they are superhuman or have special gifts or qualities. It’s perseverance.”